Here’s the latest from the crossroads of faith, media & culture: 06/19/23

![Lincoln's God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation by [Joshua Zeitz]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41x3ZXqmR5L.jpg)

The journey to Juneteenth began with Emancipation. Delivered by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1st, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation only went so far in ending American slavery as it only applied to states still in rebellion against the Union. It did not apply to slave-holding states that did not choose to secede or even to those parts of the Confederacy that had already succumbed to Union control.

Yet, despite its limited scope, it succeeded in arousing a sense of moral purpose around the Civil War and to the future of America itself. The Proclamation, which opened the door for nearly 200,000 black men to serve in the military and play an active role in the liberation, gave the impetus for the Republican Party (at Lincoln’s insistence) to make the ending of slavery throughout the land part of its 1864 platform. That, in turn, led to passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution which once and for all abolished slavery in the United States after being passed by the Congress and ratified by the states on, respectively, January 31st and December 6th of 1865.

The Civil War itself is said to have ended on April 9th of that year when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his forces to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia, however, communications being what they were in those days the last battle of the war was actually fought at Palmito Ranch in Texas on May 13th. Shortly thereafter, on June 19th, word of the ending of slavery finally reached the over 250,000 enslaved people of Texas with the arrival of Union forces at Galveston Bay. Finally, everyone got the memo and that momentous day became known as Juneteenth which has long been celebrated by African Americans culminating in it being recognized as a federal holiday in 2021.

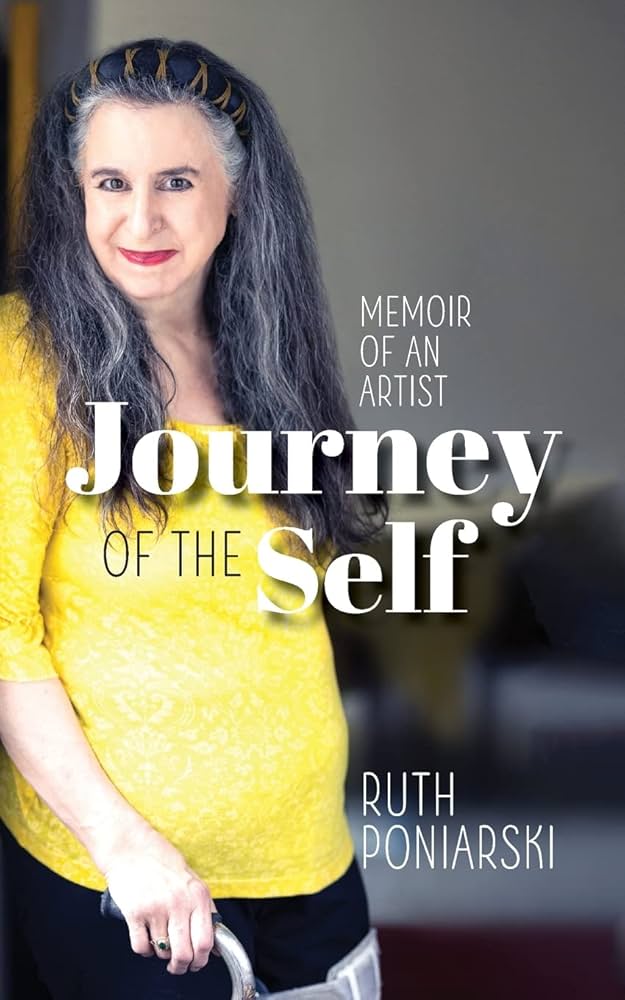

To this day, debate goes on whether Lincoln’s decision to end slavery was based more on moral conviction or more military and political pragmatism. In Lincoln’s God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation (Viking), author Joshua Zeitz chronicles the factors leading up to the 16th president’s bold decision – particularly the role of his somewhat hard-to-peg brand of faith.

JWK: With Lincoln being assassinated on Good Friday in 1865 – I believe he actually died the next morning – his murder has a symbolic association with Christianity. Was he a Christian?

Joshua Zeitz: Mary Todd Lincoln would later observe that her husband had not been a “technical Christian,” by which she meant that he was neither conventionally observant nor within the broad mainstream of American evangelical Protestantism. That said, he clearly underwent a profound religious transformation during his presidency, from firm non-believer to believer. A combination of his son, Willie’s, death, and the burden of presiding over so violent and costly a war led him to believe in God, and to see the war as part of God’s divine plan.

JWK: What were his beliefs regarding God?

JZ: Unlike most evangelical Protestants, who felt a personal relationship with Christ, for Lincoln, who was likely never a trinitarian, God was a distant and unknowable force. He came to believe that God had ordained the war in part as retribution for the sin of slavery – a sin in which both the North and South were complicit, and for which each must pay a price – and that God had further chosen him (Lincoln) as his instrument on Earth. But he did not believe it was within his power to divine whether God willed that the North win the war. He never felt the certainty and conviction shared by most evangelicals that the Union was on God’s side, and God on the Union’s.

JWK: What were his feelings regarding organized religion?

JZ: Although he and Mary rented a pew at the Presbyterian church in Springfield, where he occasionally attended services, and although he more regularly attended services at a Presbyterian church in Washington, DC during his presidency, Lincoln was never a church member and kept organized Christianity at arm’s length in his personal capacity. But he recognized the tremendous power and influence of the major Protestant denominations and openly courted and welcomed the support of Christian lay and religious leaders for both the war effort and the Republican party’s political campaigns in 1863 and 1864. He was effectively the first president to court the churches openly.

JWK: What were Lincoln’s views on slavery? Was he truly opposed on a deep moral level or was he more concerned with preserving the Union?

JZ: Lincoln genuinely abhorred slavery. After briefly retiring from politics in 1849, he returned in full force in 1854 around the issue of the Kansas Nebraska Act, which opened the door to slavery’s expansion into the territories. He was in many respects what we might call today a “single-issue politician.” The slavery issue consumed him. Unlike many abolitionists and anti-slavery politicians, whose opposition to slavery stemmed from religious belief, Lincoln hated it from a natural rights perspective. He was a man of his era, and did not view African Americans as social or intellectual equals to white people. But he believed it was a crime to hold persons as property and to deny them the right to their own labor and freedom. More than most Republican officials, he did not buckle during the Secession Winter of 1860-1861. He refused to make concessions to the South that would have opened the territories to slavery, and which probably would have bought the peace. To be sure, he flirted until mid-way through the war with colonization, by 1863 he clearly embraced emancipation not as a military strategy (though surely it was that), but also as a moral imperative.

JWK: How did the Civil War impact his faith and beliefs?

JZ: Like many Americans, Lincoln struggled to make sense of the war, which seemed in many ways so epic a historical event as to be on par with the events of the Old Testament. Religion became a lens through which many Americans, including the president, came to understand what the war was about, and what role they were expected to play. He increasingly invoked the words of the King James Bible to help his fellow Americans come to grips with the awful butcher’s bill he asked them to pay, but even in his private writings, it was clear that the war had moved him from non-believer to believer.

JWK: Did Lincoln believe that the Civil War was a sort of divine retribution for the sin of slavery?

JZ: He did, and increasingly in his speeches and public documents, he framed it as such. In this, he was hardly alone. From thousands of pulpits throughout the South, and in dozens of church periodicals and tracts, Christian religious and lay leaders made the very same point. Where he parted ways with most evangelicals was in his belief that God was punishing both the North and South for this sin, as all Americans were complicit in its long history.

JWK: If Lincoln had lived do you think the Reconstruction Era might have gone differently – and that the integration of the liberated African American people would have gone differently and, perhaps, avoided much of the racial tensions that have persisted to this day?

JZ: It’s impossible to say. Certainly, Lincoln was a more deft leader and more moral individual than Andrew Johnson. He also demonstrated a capacity to evolve, quickly. In his hands, the federal state, especially the Army, would have been a strong lever of support for the various laws that congressional Republicans passed over Johnson’s veto. But could he, any more than Ulysses S. Grant, who assumed the presidency in 1868, have summoned Northerners to continue a long occupation focused on compelling the South to accept the terms of the Reconstruction amendments, to accept interracial democracy? Maybe, but maybe not.

JWK: Would Lincoln agree with those who believe that America today remains a racist country?

JZ: One point I always press is that it’s folly to project today’s values and context on the nineteenth century, and vice versa. America today would be unrecognizable to Lincoln.

JWK: At the end of his second inaugural address Lincoln famously said “With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds.” There seems to be a lot of malice in the air these days. Some people even believe we may be on the brink of a second Civil War. What advice do you think Lincoln would have for us?

JZ: He did say that. But in that speech, he also said: “Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’” Lincoln did not confuse comity for justice. He was perfectly willing to continue the war until the South surrendered unconditionally, and until slavery was eradicated. He was not a nineteenth century analog to centrists who decry “extremism on both sides.” He knew which side was in the right.

JWK: What do you hope readers take from your book?

JZ: Religion is an under-served aspect of Civil War era history. For the majority of Americans, it was arguably the most important building block of identity and understanding. My hope is that the book helps readers consider the history of that era from a different angle, and consider how religion influenced secular events, even as secular events left a long-lasting imprint on Americans’ faith.

_____

Happy Juneteenth, everyone!

John W. Kennedy is a writer, producer and media development consultant specializing in television and movie projects that uphold positive timeless values, including trust in God.

Encourage one another and build each other up – 1 Thessalonians 5:11