Here’s the latest from the crossroads of faith, media & culture: 09/05/24

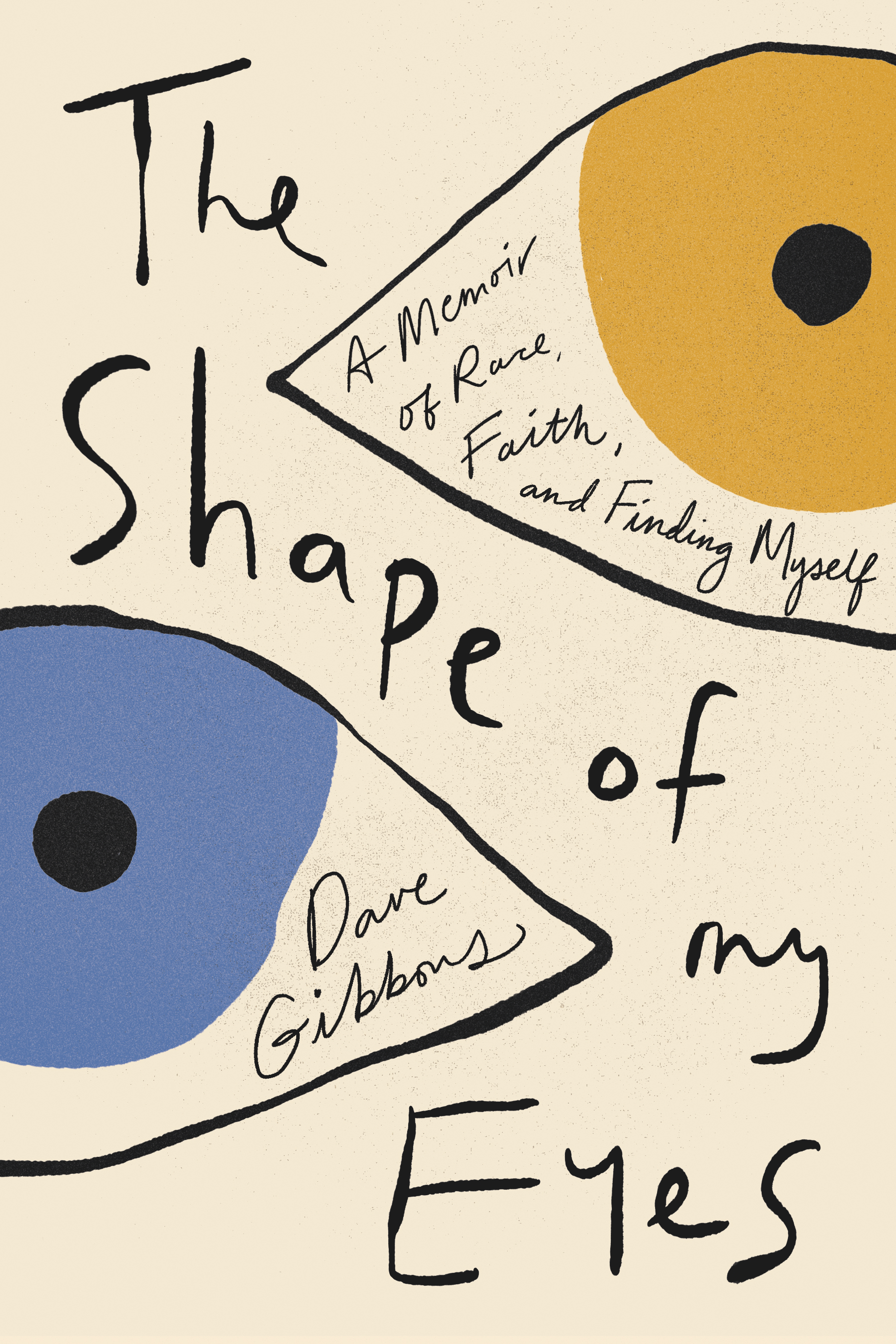

East meets west. Born in Seoul to an American soldier and a Korean mother in the wake of the Korean War, Newsong Church Founder & Pastor Dave Gibbons has long struggled to come to terms with his Korean roots and his American upbringing. His struggle took on an added dimension as his family joined a conservative church that embraced a strict, rule-based religion as they simultaneously confronted prejudice as one of the few mixed-raced families in their community. He tells his story in his new book The Shape of My Eyes – A Memoir of Race, Faith and Finding Myself.

JWK: Why did you write The Shape of My Eyes and what do you hope people take from it?

Dave Gibbons: I wrote it because I think, personally, I thought I needed to explore a lot of secrets in my family’s life. It came about after a surprising discovery of two things. One was I had PTSD. Then, secondly, I discovered through a DNA test that my father – that I always thought was my father – was not my biological father. That precipitated an exploration of my own story – like who am I really? It forced me to dig into my family, my parents and myself. The cultural moment that kind of pushed it over the ledge for me…was when I saw George Floyd killed. It just really struck me that there’s these deep wounds in our country and attitudes and systemic things that are causing such hard divisions and problems. So, I said “Maybe if I can explore some of my story there could be some type of healing and hope from it.”

JWK: Where did your PTSD stem from?

DG: I think it stemmed from two events. One was when I came home as a 15-year-old and my mom had locked herself up in a car. She was weeping. I tell people it reminded me of that girl in the Vietnam picture where she’s running naked through the streets and you can see the utter terror in her eyes and face. That’s what my mom’s face looked like. She was in her forties at the time. Then police cars converged on our house to try to coax her out – but she wouldn’t come out. We found out that day my dad had had an affair. I found out also in studies recently that that people who go through divorce – children – often suffer from trauma. So, it kind of all fit.

Then, four years after that, the second event was when I was in college as a sophomore. I got a phone call in South Carolina. My mom lived in Arizona. My sister was on the call and she was crying. I said “Hey, what’s wrong? She said “Mama was killed last night in a hit-and-run accident. A drunk driver hit her.”

So, I think those were the two (incidents) in my lifetime – but maybe also, John, it could be, you know, this theory of epigenetics where, just like they say there are physical characteristics that we carry in our DNA, potentially there are traumas that we also carry from generation to generation. There may be things I don’t even know since my mom came out of the Korean War, abuse and poverty that are still within me from her and her parents.

JWK: Can you tell me a little bit about your father and his past?

DG: My father lived in Michigan. He was like a typical young American but he was in poverty amongst a big family of boys. He was baseball player and football player…He joined the Air Force as a young man and was based in Korea where he met my mom. That’s when they started living the American Dream. He actually put his name on my birth certificate. That’s why I thought he was my father. He (returned) to the states (to live) with my mom, me and my brother and sister. Then he started building the American Dream with my mom.

JWK: So, he met your mother in Korea – but he was not your actual father.

DG: Yeah. I didn’t find that out until a few years ago.

JWK: How did you make that discovery?

DG: I took a DNA test. I was going to try and prove my wife wrong. She had always thought that he wasn’t my biological father but he had told me that he was and my birth certificate said he was. Genetically, you can look one way even though you have two different races of parents. So, because of that, I just believed that he was probably telling me the truth. So, after he died – and to prove my wife wrong – I said “Okay, I’ll take this DNA test.” I did and it showed that I was almost 100% Korean. So, that caused me to take a deeper exploration (to learn) more about my mom and the secrets of my mom and my dad – as well as like who’s my biological dad?

JWK: So, you were born in Seoul and raised in America. You say you felt “not quite American and not quite Korean.”

DG: Yeah…It wasn’t until I was in fourth grade that I even thought about my race. It was because people were teasing me about the shape of my eyes…They’d call (me) racial slurs like “chink” or “Chinaman” or “slant eyes.”

JWK: Where did you grow up in the US?

DG: It was Arizona.

JWK: And the other kids would make fun of your race?

DG: Yeah, they would make fun of my race and the shape of my eyes. Because I had the same skin color, it always had to do with my eyes. They would (also) make fun of my mom and brother and sister (for being) Asian. So, that’s when my racial identity became clear – that I’m not like anybody. I felt like I was culturally American but I didn’t look American. So, I didn’t feel at home.

It wasn’t until later, as an adult, that I went to Korea and I realized that they also didn’t see me as Korean because I didn’t speak the Korean language. So, I felt like this perpetual outsider (who) didn’t have a home. It wasn’t until like the last ten years that I realized, you know, I’m 100% Korean and I’m 100% American in terms of culture.

So, I said “1+1+3.” Three is like a third culture. I said “Man, that’s like the ‘and.’ It’s the perfect ‘and’!” If you think about Jesus, He’s both Heaven and Earth. He was divine yet he was human. You know, we’re supernatural yet we’re natural; we’re beautiful yet we’re broken. We’re really this complex “and” which (is related to) God. (Jesus) prayed that prayer “Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done on Earth as it is in Heaven.” So, I said “Man! He prepared me to understand this transcendent place where I can be a combination of things – where I don’t completely understand it but I can be holy in both.”

JWK: You went to Dallas Theological Seminary, right?

DG: That was a grad school for my Master of Theology. My underground was Bob Jones.

JWK: Is that where you experienced systemic racism?

DG: Yes, at Bob Jones.

JWK: What was that experience like?

DG: The dean of men called me into the office and said I couldn’t date Caucasians anymore because The Bible (supposedly) says (according to) the Tower of Babel (story God) wanted people to be divided, not to stay together. Secondly, they said, He told Israelis not to marry foreign women. We know that (refers to) foreign gods.

I realized, after doing some study in this, that Asians were actually allowed to date (white people). From my understanding, there was a famous man by the name of Billy Kim who was a translator for Billy Graham at the biggest crusade ever for Billy Graham – in Korea. Billy Kim went to Bob Jones. He later would marry white and was considered a leader and someone that Bob Jones lifted up.

So, what was the issue then? I realized the issue was (that) in the fifties there was Brown v. Board of Education where the Supreme Court said that schools cannot segregate. Bob Jones did not abide by that. It wasn’t until 1971 (that they allowed) the black community on their campus (but only if) they were (married). They wouldn’t even let singles (on campus). My guess is that to be consistent, they couldn’t just target the black person or black community. They had to also try bring in these other races to try to be consistent from what they believed was a scriptural interpretation.

JWK: I remember that case, actually. They were like exceptionally conservative – if conservative is even the word for it. Is Bob Jones University even still around?

DG: Yeah, they’re still around. They recanted that position in (2000) on the Larry King show on CNN. They apologized, I believe, and recanted that position – but I realized that this is like a systemic racism that’s within a lot of our institutions…and it specifically targets the black community which has had racism against them for 400 years plus.

JWK: Did you have a different experience at Dallas Theological Seminary?

DG: I did. Dallas Seminary was a really beautiful place for me. From the Bob Jones community perspective they thought I was becoming liberal even though (Dallas Theological Seminary) is still very conservative – but, at that time, the professors there were the ones writing a lot of the Evangelical books and leading in Christian thought…from a western perspective. I got to sit at the feet of some really brilliant Christian leaders, theologians and scholars. To me it was a wonderful time just to be able to dig into the Scriptures, understand my spirituality and become who I felt God wanted me to be.

JWK: Who do you feel God wants you to be?

DG: At that time, I think it was about being a pastor or a missionary – that that was the way to fulfill my calling. I was focused more upon the occupation. I think, since then, my understanding has evolved because I was told that that was the highest calling, to be like a pastor or missionary but I realize that that was a tension. It was kind of like David when he was trying on Saul‘s armor. It didn’t quite fit. The way people are describing a calling from an occupational perspective, it didn’t fit me because I also felt like I was an entrepreneur – and also an artist. So, I didn’t know how that all worked together. It was basically too binary.

I realized over time that my identity wasn’t wrapped up in my occupation – whether it was a pastor, an artist or a writer. An occupation is more like a piece of clothing that I can express myself through but it doesn’t necessarily define me. Who I am is really this person that’s made in the image of God. I’m a son of God. Every human being is uniquely made in His image. They have a beauty about them where they carry His unique imprint of His supernatural energy as well as His moral character and the way He can move and flow in the world.

So, yes, my perspective shifted from just an occupational focus to understanding my uniqueness as a human being that’s empowered by God. Then, in terms of what I do, I found it based in Genesis 1 and 12. Genesis 1 is “Be fruitful, multiply and secure the whole Earth.”…Genesis 12 says “I bless you to bless the nations.” I said “Oh, I’m supposed to do that too!” I’m supposed to receive the blessing of God but then bless others – but not in a religious type of way, more like how blessing was defined in Scripture (which) was you see people, you know people, you affirm their uniqueness and then you give them access to resources. So, see, know, affirm and give. No matter what occupation I have, if I can do these things of freedom and blessing, I can really live out a really magical life of interaction with God – but also human beings.

JWK: In 1994 you founded the Newsong Church and ten years later in 2004 the X Global Network of of 3Culture Leaders. Can you tell me about those organizations and how they reflect your purpose?

DG: Great question. Newsong is a local community for me to develop other people in their faith in God and one another. I liken it to a local X-Men academy where we’re looking for misfits and mutants. Our role is to equip them so they’ll know how to work with their superpower – but also their own brokenness so they don’t destroy themselves and destroy others. We see ourselves like a school where we’re training and developing people. We’re not meant to be like what people call this “City on a Hill” where we’re everything to everybody. I think we’re uniquely called to specifically serve the under-resourced, the marginalized and the misfits.

The Xealots – or X community – is my global platform to do the same thing. It’s an X-Men academy for global leadership. It’s expressed through different ways. It’s not just a church form but also it could be through a Mexico City anti- human trafficking center to rescue young girls or it could be in Thailand where we develop economic incubators to help those that are suffering from abject poverty so that the girls won’t have to go from the northeast to Bangkok to sell their bodies…or it could be in Brazil where we’re coming alongside the next generation of leaders to help them figure out how to source government leaders, business leaders and artists. Xealots is our global X-Men academy.

JWK: Superheroes, it sounds like – which is great!

You’ve talked about systemic racism in America and, particularly, what the African-American community has been through. How would you compare those experiences with what Asians have gone through in America.?

DG: It’s not apples to apples. I think the history of African-Americans is dark, it’s heavy and it’s evil…It’s different but it’s also the same. I think we can say that there are similarities. They’ve both experienced injustice but differently. We’ve both experienced racism and discrimination – but, again, differently. I can’t speak for the black community but, from what I know of the Asian community, when the Chinese built the transcontinental railroad they were treated like slaves. Very poorly. And then the Japanese internment camps and (before that) the Exclusion Act…where Asians weren’t permitted to immigrate to the states. Systemic racism is sometimes not so blatant but people won’t get jobs or they won’t get loans.

JWK: Asian-Americans have, of course, done pretty well economically in America, right?

DG: They have but that’s also a model minority myth that’s helped to use Asians to argue against black protest. The truth is, amongst Asian-Americans, we have a lot of people that are struggling, that also suffer with poverty. You see a cream of the crop sometimes that are lifted up from a media perspective but we also have a really large size community that suffers.

JWK: From a perspective of faith in America, do you feel that things have significantly improved over the years – or do you see that as not being the case?

DG: I think for the institutional church in America, it’s deconstructing. I think we’re in a really dark state. If you look at the polarization, the tribalism, the willingness to resort to violence. Recently a study was shown that was in a major publication that said that twelve-million Americans are willing to resort to violence if their candidate is not elected. John, that’s 4.4% of the American population. So, I don’t know if institutionally it’s changed. I think it’s more polarized, more prone to violence than I’ve ever seen in my lifetime.

JWK: Just quickly, as I know we’re just about out of time, is that because faith has dwindled in America?

DG: I don’t know if faith has as much as I think there’s been disappointment with religious institutions and their leadership not really living up to what we declare about loving the outsider, loving the refugee, loving those that are hurting. We preach it and we say it but I think this next generation, you know, they’re honest. To me it’s really beautiful that they’re honest and actually calling out what they know Jesus would say – that Christians aren’t living this way.

So, I actually have hope for the next generation, more than ever before. I feel like this is the most spiritual generation I’ve seen in my lifetime. They’re hungering for something something that’s real and authentic but what they’re seeing amongst a lot of the Christian community is something that inauthentic and not congruent with what they know Jesus to be or what He would declare.

John W. Kennedy is a writer, producer and media development consultant specializing in television and movie projects that uphold positive timeless values, including trust in God.

Encourage one another and build each other up – 1 Thessalonians 5:11