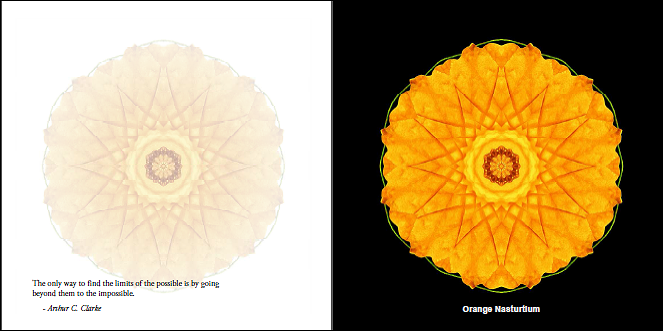

NOTE: This is the first draft of the “Presence” essay in my forthcoming book, Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas.

Responses and comments welcome, no matter how brief.

Presence: Now, be, here

Copyright 2013 David J. Bookbinder

I was 20 when I first encountered Baba Ram Dass’s square, purple-covered Be Here Now, the book that launched many of my generation on an Eastern-inspired journey. I was walking though the student center of the University at Buffalo when I ran into a high school friend sitting on the floor outside the bookstore, guitar at his side, leafing through it. He handed it to me. Be? Here? Now?

More than 40 years later, I’m still asking what that means.

One of my most important teachers is Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese monk whose simple exposition of Buddhist principles has been life-changing for thousands of people worldwide. Like Ram Dass, his most compelling observation is that we are already who we are, already in the only moment actually available to us. “The past is gone, the future is not yet here,” he says, “and if we do not go back to ourselves in the present moment, we cannot be in touch with life.”

It seems so simple; yet being here now is not easy for most of us. We are inundated with stimuli that trigger us to live in the past, in the future, in a fantasy world – to be anything but ourselves, anywhere but here and now. And because we are not taking in all of what the here and now offers, we strive to fill our emptinesses. But what we consume often leads only to wanting more.

Sometimes we want things, and we hunger for material goods to match or exceed what others have. Sometimes we want feelings, and we seek out passion, excitement, happiness, love. Sometimes we want status, and we do whatever it takes to obtain recognition, appreciation, power. Sometimes we want even more: to be who others seem to be.

I recall my father after six weeks in Southern California, stranded there by Buffalo’s Blizzard of ’77. Exploring the West Coast with his sister, he saw how “the other half” (the 1%) live. Following his return to his much humbler life, for weeks he could speak of almost nothing but the mansions, yachts, and other signs of extreme wealth he had witnessed. The subtext of his response was, “What did I do wrong? How come I don’t have that?” Older, now, than my father was then, I also sometimes struggle with envy. And I catch myself thinking, “What did I do wrong? How come I don’t have that?”

As babies we don’t worry about wanting more, and we don’t desire to be anyone but who, where, and when we are. Then we grow older and widen our view: “Now” includes memories of the past and plans for the future, “here” extends to where we have been and where we might be heading, and “being” contains all our previous selves and the seeds of who we are becoming. This is not a bad thing. Without that broader view, we could not learn from history or plan for either our personal futures or the welfare of subsequent generations. The problem occurs, as John Lennon put it, when our lives become what happens while we’re making other plans.

One impediment to being-here-now is carrying our past experiences into the present. Many of us move through our lives unconsciously replicating old relationships, repeating unhealed shame, regret, fear, sadness, anger. Or we continue to obey the limitations our earlier circumstances imposed on us, screening out opportunities for something new to occur. “That’s just how I am,” we say. We learned these lessons well; we grow older, but some parts of us stay frozen in time. I see this most clearly in PTSD sufferers, whose traumatic memories and woundedness are endlessly recycled. But the same process occurs more subtly with other old hurts. Much of what I do as a therapist is to help clients break the connection between what happened to them in the past and what they believe is happening now.

Living in the future is equally problematic. An archetypal example is the protagonist of Henry James’s novella The Beast in the Jungle, who believes his destiny will be shaped by a momentous event that lies in wait like a “beast in the jungle” and spends most of his life waiting for this to happen. Only when it is far too late does he recognize the anguishing cost of this strategy. On a less dramatic scale, many of us fritter away our limited time on the planet fretting about situations over which we have no control, trading what is here, now, for a fictional future. Or we calculate ways to control our fate. One man I knew, who was extraordinarily gifted at recognizing patterns, was equally skilled at influencing other people. He combined these talents to try to make things go as he planned, and he often succeeded. But his “success” did not make him happy. Instead, he longed for unpredictability and freedom from what he came to call his “secret hidden agendas.”

Presence – being fully oneself, in the present, responding authentically – is pivotal to successful therapeutic relationships. Toward the end of his life, Carl Rogers, pioneer of modern psychotherapy, wrote, “I find that when I am the closest to my inner, intuitive self – when perhaps I am somehow in touch with the unknown in me – when perhaps I am in a slightly altered state of consciousness in the relationship, then whatever I do seems to be full of healing. Then simply my presence is releasing and helpful.” In the best case, presence goes both ways. When clients are also fully present and responding authentically, each session functions as a laboratory in which what they bring in from their lives metamorphoses, and then is brought out again into the world, transformed. It is hard to overstate the power of presence.

A moment like Rogers described launched me on the therapist path. In the midst of a chaotic phase of my life, I took a class in Rogers’s form of therapy. Early in the semester, I asked the professor if she could show, in a demo session, how it worked. When nobody else volunteered for the job, she suggested I be the client.

At first I was self-conscious, but within minutes I had forgotten about the other students; I was fully engaged in my interaction with the professor/therapist, and also with something deep within. At one point the professor responded to something I said with an anecdote about a parallel experience. I found myself responding to her in the empathic way she had been using with me. In that moment I knew not only that I might learn to do Rogerian therapy, but that I was already doing it. The rest followed.

Presence is seldom “perfect.” Minds wander. Feelings intrude. Confusion… confuses. But usually, all that’s needed to reestablish a more present state is to become aware of the distraction and come back into contact.

Practice helps. The key to presence is mindfulness. Specific mindfulness practices such as meditation, mindful walking, and mindful eating encourage moment-to-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, actions, surroundings, and interactions. But many other activities can also exercise and strengthen the “presence muscle” if done with a mindful intention. Body-and-mind-centric activities such as yoga, tai chi, martial arts, and dance, or expressive arts that require close attention, such as drawing from life or improvisational music, promote presence. For me, photography and motorcycling have been helpful. Each in its own way forces me to pay full attention to what is going on right here, right now, with all of who I am.

Even simple actions such as walking, driving, and household chores are opportunities to practice presence. Standing still in traffic, waiting for a bus, being confined to a boring meeting or a hospital bed can all, with the mindfulness mindset, become experiments in being present. Unpleasant sensations and experiences can also be converted to practices in being here, now. An unexpected gift of the injuries I have sustained was discovering that pain can enhance presence, and that presence makes pain more bearable.

Presence comes naturally for many of us in moments of extremity. The sensation of time slowing down when something dangerous is happening is, I believe, because in those intense moments we are entirely present. Unlike our more repetitive periods, these moments are packed together tightly, and each one registers.

The days and weeks immediately following my near-death experience were like that. Everything was new, as if I were apprehending the world from the perspective of a child. So are all the moments that divide everything into “before” and “after”: the moment you find out your husband or wife is having an affair, your boss tells you you’re fired, your car slides out of control, your doctor tells you you have cancer. Or, conversely, the moment a child is born, a lottery won, a love relationship consummated. These moments, too, contain more presence in them than a month of ordinary and predictable experience, and they hold a key to incorporating more presence, and perhaps also more passion, into those in-between times.

At the end of our days, if we are not content with the present moment, then it won’t matter much what happened in the past because that will all be over. Nor will we be able to count on a “better” future. So it behooves us to learn, now, to fully take in our present moments, else, like Henry James’s protagonist, we realize only too late that we have been waiting for the beast in the jungle that never comes.

Discussion: Facebook Flower Mandalas page

Subscribe to the Flower Mandalas mailing list

Request the 15 Flower Mandalas screensaver: Fifteen Flower Mandalas

Text and images © 2013, David J. Bookbinder. All rights reserved.

Permission required for publication. Images available for licensing.

flowermandalas.org