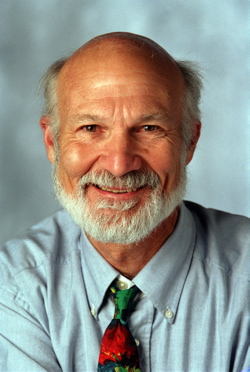

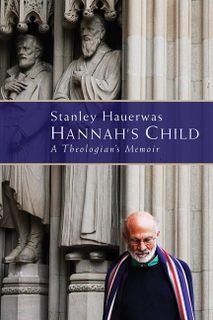

A personal memoir from a theologian? Now, that’s not something you see very often.

And not just any theologian. This is Stanley Hauerwas, a man that Time magazine lauded as “the best theologian in America.” I’ve got no argument with that. In Hannah’s Child, we learn about his unusual, rich life–his working-class background as a Texas bricklayer, his struggles to care for a wife with severe mental illness, and the books and friendships that have formed him.

Flunking Sainthood: You’ve written elsewhere that this book has already elicited quite a response from readers. Why do you think that is?

Hauerwas: I think the book tells events in my own life that people identify with in a very emotionally direct way. When I started to write Hannah’s Child, I realized that this had to be a book of passion, to have a certain kind of vulnerability. I think that people respond to that. Therefore they write to me – they write very painfully and appreciatively about their own lives in that way. I think also that people respond to what they often describe as the straightforward honesty with which the book is written. They seldom find that in religious discourse.

FS: Along those same lines, you talk in the book about not being sure you were a Christian until well into your career.

Hauerwas: If you ever think you’ve got it right, you probably don’t. I think that while some people have described Hannah’s Child as a kind of Augustine’s Confessions, it’s not anywhere close to being in that league. But clearly Augustine, even through his conversion, is still not sure he knows what he’s about. Even in Book 11! That seems to me appropriate. To be a Christian means you become a part of the most significant story the world has ever heard. You don’t become part of that without an ongoing questioning of what it means to become part of that.

FS: You grew up as a bricklayer’s son, and started going out on “the job” around age 7. You say that experience has shaped your approach to theology. How?

Hauerwas: It’s what it means to go through the diverse skills to become a bricklayer. When you go out on the job that young, you’re given a task that you can perform. My first job was to catch bricks as they were thrown up on the scaffold. But there’s a hierarchy of skills you learn, first by being a laborer. I labored for 7 or 8 years before my father let me start laying brick. There’s a kind of hierarchy of skills I oftentimes think is absolutely crucial for how one slowly learns to do this very odd work called theology. It takes years to acquire the kind of confidence in words and their relationship to one another that theology requires. How do you learn to talk about God in a way that doesn’t betray the mystery of what God is?

FS: Your book is not just a personal history but an intellectual one, a wonderful account of the books and people that shaped you. I found myself really wishing for an index so I could look things up later.

Hauerwas: Well, we thought about it. But memoirs just never have an index, so we decided against it.

FS: The memoir is pretty open — not just about personal struggles but professional conflicts as well. Did you use the real names of scholars and administrators?

Hauerwas: Yes, everyone has their real name. I wanted to write honestly, and you need to write about real people. Real people have real names. It never occurred to me to make anyone’s name up. There’s a very thin line between cruelty and honesty, and I didn’t want to be cruel, but I also needed to tell the truth about some of my relationships.

FS: Speaking of honesty, a good portion of the memoir discusses the pain of your first wife’s mental illness, which readers have responded to.

Hauerwas: I think it elicits a kind of loneliness that’s characteristic of our lives in general, and in particular our lives that are captured in certain forms of suffering that don’t seem sharable but that resonate with many of us today. We’re just not sure what it means to be able to share our lives.

FS: Do you think that kind of isolation is getting worse in our culture?

Hauerwas: Yes. Yes, I do. It has to do with a lack of shared language and moral judgments. Therefore human relations lack a kind of immediacy that makes possible our ability to locate friendship in ways that is sustainable for years.

FS: As you wrote the memoir, were there elements of your life that became newly painful as you relived them?

Hauerwas: I think so. Like the fact that my parents let me go on [to become a scholar], and the further I went the less we had in common. I feel still that intensely. The fact that I spent my life in universities in a manner that I no longer have close identification with bricklayers is a pain to me. Of course, obviously, living again the years with Anne is painful.

FS: Despite all the pain, it’s a cheerful and often funny book.

Hauerwas: I’m a happy and productive person. I’m very fortunate; I was born with happy genes. I’ve got a lot of energy. I also wonder in the book if sometimes just my ability to just keep going contributed to my wife’s illness. The more I tried to make life better for her, the worse it got.

FS: What are you working on now?

I’ve just finished a book for Brazos called War and the American Difference: A Christian Alternative. It’s an attempt to remind us that the United States has been at war for ten years, and no one has thought that much about it morally or theologically, so I try to do this in the book. In particular I try to give an account of the morally compelling character of war. The fact that we keep having war means there’s something morally compelling about war.

FS: In Hannah’s Child you talk about being profoundly influenced by the Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder, and recount that he’d said he had only ever made one real convert to non-violence: you.

Hauerwas: Yes. And he felt deep ambiguity about it!

FS: Well, thanks for writing this fascinating book. But curse you for giving me leads on so many other great things to read. Now I want to read all 47 novels of Anthony Trollope. Darn you!

Hauerwas: Oh, it’s great. It’s great.