What would it be like to really know your neighbors, and vow never to leave them? To commit to living in your same house, in your same neighborhood, for the rest of your life?

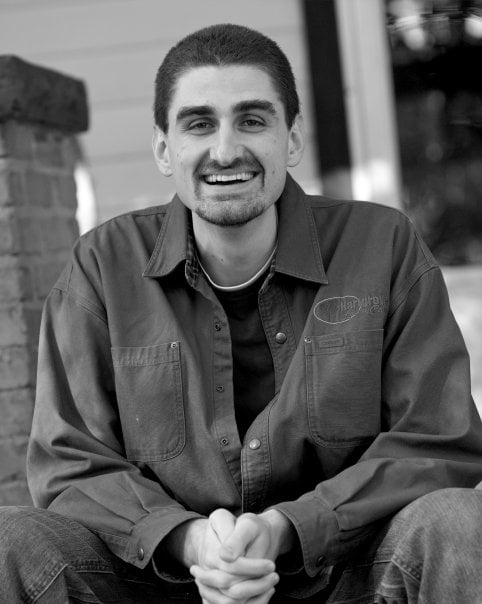

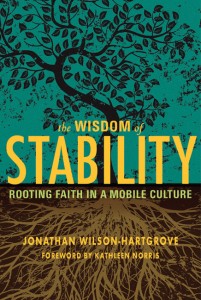

That’s what Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, author of The Wisdom of Stability (Paraclete, June), has vowed to do. Jonathan and his wife live in Rutba House, an intentional urban monastic community in Durham, North Carolina. No, they’re not celibate monastics–they actually have two kids–but they do resurrect some ancient Christian ideas about staying in one place, serving their neighbors, and slowing down.

FS: Jonathan, we live in a country where the average person moves every five years. In just one year when I was 21, I lived in four different states! “Stability” sounds so middle-aged and un-sexy. Tell us what’s cool about it.

Wilson-Hartgrove: I have a friend who likes to say, “Staying is the new going.” Maybe there is a movement stirring. But I hope it’s more than a fad–more than the “new cool.” The cool chasers have over-advertised to this generation of emerging adults, and I think a lot of us are tired of chasing promises that feel empty. The folks who find their way to our community all say the same thing: we want a life that’s real. That means knowing a place and its people. It means being known. And that means sticking around.

FS: Do you think that more people are becoming attracted to the “wisdom of stability” and the New Monasticism precisely because Americans are so transient and rootless?

Wilson-Hartgrove: This is the great paradox of our hunger for community. We feel the need for community all the more because we lack it–we’ve been starved by individualism into a desperate hunger. But the people who are most starved have the least resources to make community happen. This is why we need the wisdom of those who’ve gone before us. When we got into community, some of us thought we were doing it for the first time. It was a great relief to meet some Benedictines and learn that Christians have been doing this for over 1500 years.

FS: So can you walk us through a typical day at your house?

Wilson-Hartgrove: We get up in the morning and pray together. (The Benedictines taught us to start the day with common prayer.) Then we’re off to work. Most of us work in the neighborhood or with issues that affect our neighborhood. We try to stay close to the neighborhood and its needs. We come together again to eat our evening meal. And our table is open. If we meet someone on the street who’s hungry, we invite them home for dinner. Our table is a place to listen and a place to be heard. It’s a symbol, really, of what we’re trying to be about–a people sharing life across dividing lines, moving from relationship into action for the sake of one another’s healing.

FS: And how do you all afford to live this way? Do you pool all of your money communally, contribute a certain percentage to a common house fund, or what?

Wilson-Hartgrove: This is important. Stability (or the lack of it) is an economic issue for all of us. So often people feel like they have to move for a job, even if they know they’re leaving great friends or a great community. One of the reasons Rutba House shares money is so that all of us can stay put in the midst of an economy that doesn’t value stability. When this economic crisis hit a couple of years ago, one of our members lost his job. It wasn’t immediately clear what he’d do next. But he never thought about leaving. We all said we’d take care of him and his family until he found another job here.

FS: What kinds of things do you do for and with your neighbors? What’s the Walltown neighborhood like?

Wilson-Hartgrove: Ours is a neighborhood in a university town that has always been home to people who do service work. It’s a classic Southern town, so the division is racialized. The folks who wash the toilets at the university are black. Some of them still call Duke “the plantation.” We didn’t come here to start programs or “fix” problems. We came because this is a community that knows how to take of each other. Those of us who relocated came as disciples. But one of the things we’ve learned is that we come from privilege and we bring some of that with us. So we go with friends to court. We vouch for them, and their sentences are often reduced. We advocate for programs and policies that will make it easier for our friends. And in a few cases, when we didn’t find anything already in place to meet the particular need, we’ve helped start new things.

FS: Kathleen Norris provides the foreword for your book. Score! How did that happen?

Wilson-Hartgrove: No one has done more to open up monastic wisdom to modern people than Kathleen. She’s a gracious friend, and I’m so glad she was willing to introduce the book.

FS: There’s a surprising chapter in your book about “midday demons”–on the acedia that sets in when ambition, boredom and restlessness threaten to take over. So, a personal question: what are your own temptations? I notice that the chapter has great stories about other people, but almost nothing about you.

Wilson-Hartgrove: Well, I tried to be honest in the “Front Porch” sessions between each chapter–little confessions I wrote about what all of this means for me. Truth is, all of these temptations matter to me because I’ve faced them myself. Because I was raised by people who know how to get things done, I think ambition is probably my biggest temptation. I’d never leave because I get bored. But I’m tempted to leave almost every day because I imagine I could get something really important done some place else. Writing a book about stability doesn’t make that go away. In some ways, it makes it worse. I have to convince myself that it’s better to stay and practice this wisdom than to run off and talk about it on a 15-city tour.

FS: I loved your book, but I’m sorry; I’m not going to be taking monastic vows anytime soon. What’s your advice for someone like me, who would like to put some of this “wisdom of stability” stuff into practice but isn’t ready to make a lifelong commitment to a particular location?

Wilson-Hartgrove: The incredible thing about stability is that it seems God is ready to give it to each of us wherever we are. When Jacob is on the run, catching sleep under the stars, God shows up and says, “This place is holy ground. I can meet you here.” That’s good news for us modern souls. Because God is willing to meet us even on the run, we can start paying attention wherever we happen to be. We can get a common prayer book and, even if only once a day, join the great tradition of those who’ve been praying these prayers steadily for millennia. We can love the person in front of us as if we’ll never leave them–even if, for whatever reason, we must. Every act of establishing roots of love matters. Who knows, you might just stumble into a rhythm of life that’s so irresistible you never leave.