AIDS isn’t much on people’s radars anymore, at least not in the United States. Combination-therapy drugs have made what was once a death sentence–an HIV positive diagnosis–into a manageable, if debilitating, condition. But what’s it like to live with the disease, to have a family and a job, knowing all along that you’ve dodged a deadly bullet?

AIDS isn’t much on people’s radars anymore, at least not in the United States. Combination-therapy drugs have made what was once a death sentence–an HIV positive diagnosis–into a manageable, if debilitating, condition. But what’s it like to live with the disease, to have a family and a job, knowing all along that you’ve dodged a deadly bullet?

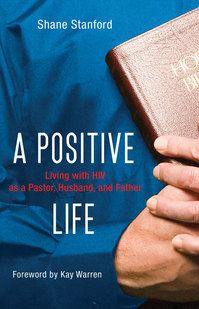

Shane Stanford’s been navigating this road since his diagnosis at age 16. He was the first HIV-positive person to be ordained a United Methodist pastor. Reading his new memoir,

A Positive Life: Living with HIV as a

Pastor, Husband and Father, you’ll be struck by the fact that his diagnosis is not the only positive thing about him.

Q: Shane, you were diagnosed with hemophilia as an infant, and today you are also HIV positive and dealing with Hepatitis C. Yet you pastor a very large church, you are married and have three biological children, you host a television show and you’ve authored several books. Did you ever expect your life would look like this?

Shane Stanford: I’m not sure any of us expect our lives will turn out exactly as they do. However, I had dreams from the time I was a little boy about accomplishing certain things. First of all, I was not going to be a pastor. My undergraduate degree is in “Pre-law” and I thought I would be an attorney. In fact, even after serving a small student pastorate, I still thought I would finish college and go to law school. But, God led me in a different direction.

Mostly though, my life changed the morning I woke up as a 16-year-old boy who, only the day before, had been the President of the class, captain of the golf team and dating the prettiest girl in school, to be told on this day that I maybe had 2 to 3 years to live.

I accepted the news like anyone my age, I suppose, except that my family had already instilled a strong faith ethic in my life, and I had a lot of good people praying for me. I also had the support of that young, prettiest girl who decided to stick with me even after hearing the news of the diagnosis.

But, more than anything, my grandfather is the one who affected my life most from that point. I write in the book, how my grandfather posed a question to me, “What are you going to do with this thing?” He was a good, country man who didn’t talk about AIDS and such topics, and he certainly did not cry. But, on this day, he wanted to help me walk through the pain and grief. I told him that I did not have a choice. He quickly replied, “we always have a choice”. I couldn’t see one. In fact, I felt that my choices had been taken away.

But, my grandfather cast the choice like this. You can get in the corner and have a pity party about the raw deal you have been given. And, he said that he would even get in the corner with me if that is what I chose. But, he said he knew me and believed that I would make another choice–one that would make the most of everyday and make life matter.

So, I would have to say that from that day I decided that this disease may kill me but it would not define me. And, as God opened one door, or when one struggle or another raised their ugly heads, we simply tried to be faithful.

Now, I am not saying that if you live like me, you will be blessed and have all these wonderful things happen. But, there is something powerful about drawing close to this God who loves you so and trusting that whatever may come your way, the two of you, together, can handle it.

Q: You were diagnosed with HIV (which you contracted via treatment for hemophilia) in the late 1980s as a teenager. What did the public know about HIV at that time? How has public perception of HIV/AIDS patients changed over the past 25 years?

Stanford: At the time I learned of my HIV status, it was very dangerous both physically and relationally to let anyone know. In fact, I remember my mother saying that we could not tell anyone because we couldn’t be sure of how people would respond.

Most of this was just because people didn’t know enough. But, I remember young men like Ryan White and Ricky Ray whose lives became very public because of the disease and because the discrimination that surrounded it.

Of course, a lot has changed in terms of the perception of the disease itself. People are not as frightened of it. I remember being in the hospital in the early 1990’s and having the orderlies leave my food outside on the hall floor because they were scared to bring it in. You don’t hear of a lot of that anymore.

Most of the discrimination and stigma remains socially. You don’t find a lot of people who are HIV positive in positions of power or importance, unless they started there. And, there are still a lot of people who judge the disease based on “how” the person contracted the disease.

So, yes, we have made a lot of ground but we still have a lot of work to go.

The vast majority of HIV positive people are living lives just like everyone else, except they have to take a lot of medicines. It just so happens that my life is so public. It had to be that way and I want to help it be that way for others.

Q: How can the church be a better support to those who struggle with chronic illness?

Stanford: I’ll answer this one as a pastor first. It really depends on the illness. Medicines are great and people are living longer and healthier. But, most of these meds have horrible side effects that can be as debilitating as the disease. There needs to be lots of conversation, honest conversation, among people who are chronically ill and those who live with them, are friends, the people they work with, so that everyone understands the circumstances. Hiding this kind of info inside will only lead to confusion down the road.

But, the church can help by offering a place of peace and rest for these folks. Classes that help with basic issues of living healthy and well. Providing support groups. Providing community opportunities, but also providing ways for the chronically ill person to serve as well. Most folks who are chronically ill do better when they have a goal and a purpose. The church provides the best purposes in the world.

There are other dynamics that will be helpful too including just building safe places for people to know and be known. Nothing substitutes for that.

Q: How is the church doing in ministering to those with HIV/AIDS? How can we better show the love of Christ to the HIV community?

Stanford: I would give ourselves at C- but not just for HIV but for so many of the marginalized and forgotten of our communities. We are driven by our sefl-centered, consumeristic tendencies that dominate our views of life values and people that we miss what it means to live as brothers and sisters in Christ together.

Now, the Church is infinitely better than those very sad, horrific early days. But, we can always improve, always become the “hands and feet of Jesus” more.