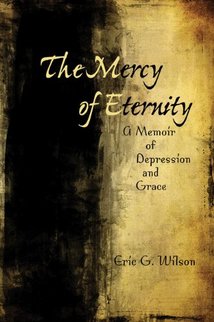

If you’re unlucky enough to be depressed, our society tells you to pop a pill and put on a happy face — anything to avoid wallowing in sadness. But today’s guest blogger, Eric G. Wilson, suggests in his new memoir The Mercy of Eternity: A Memoir of Depression and Grace (Northwestern University Press, 2010) that it was only when he gave himself over to the darkness that he began to get well. For him, the path to healing lay not in pat denial or even a victorious overcoming of his illness, but accepting it as a friend.

If you’re unlucky enough to be depressed, our society tells you to pop a pill and put on a happy face — anything to avoid wallowing in sadness. But today’s guest blogger, Eric G. Wilson, suggests in his new memoir The Mercy of Eternity: A Memoir of Depression and Grace (Northwestern University Press, 2010) that it was only when he gave himself over to the darkness that he began to get well. For him, the path to healing lay not in pat denial or even a victorious overcoming of his illness, but accepting it as a friend.

His is a powerful story (see reviews here in the Raleigh News-Observer and here in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune). I notice that both reviews use the word “harrowing” to describe Wilson’s journey through darkness to grace, which was precisely my response to the excerpts I read. Although it’s only 108 pages, the book packs a wallop. May it be a light to others in dark places. –JKR

I grew believing that the greatest sin is quitting. My father, a football coach, informed this conviction, but other sources could just as well have inculcated it. America, after all, has prided itself on gumption: the resilient rebel overcoming the odds.

Whatever the origin, I came of age to a soundtrack of clichés: “Winners never quit and quitters never win.” “So stick to the fight when you’re hardest hit– / It’s when things seem worst that you must not quit.” “Winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing.”

I tenaciously held to these tenets. For me, as for much of my nation, “waffling” was anathema, and the mantra was “Stay the course.”

Eventually, optimism nearly killed me. Despair, merciful, kept me alive.

Until I reached my mid-thirties and fell into a clinical depression, I tried desperately to adhere to what William James has called “the religion of healthy-mindedness,” grounded on the notion that God has created a world that “is absolutely good,” and so the correct response to the cosmos is the eternally positive attitude.

Not surprisingly, this mode dominates America, still fevered with utopian dreams of being a city upon a hill, visible to all, blessed by God. Ours is what theologians would call a “cataphatic” sensibility: a belief that God is accessible in positive terms. He is good, He is omniscient, He is just, and faith in these predications produces a robust life.

Too much health can be risky. Existing until the middle of my life with healthy-mindedness as my sole goal, I expected the world to rise to my desire to be happy. When depression hit, I was devastated, and almost undone.

Often, I experienced a painful gap between the well-being I expected and the dejection I was suffering. This rift exacerbated the depression: I was sad, but also sad that I was sad, and then further sorrowful over the sadness over the fact that I was sad, and so on.

Other times, I repressed the unhappiness. But this self-delusion enclosed me in an egocentric cell in which I perceived only what I wanted to perceive and demeaned the remainder to illusion. I severed myself from the actual.

At the depth of my depression, I nurtured this narcissism. I cared only for what might raise me from my malaise, through sympathy or encouragement; and I rejected whatever aggravated my unease.

Suicide became seductive, promising an escape from the torment of staring only at my petulant self, day after day. What saved me was the death of hope.

In preparing to teach William Blake–I’m an English professor–I came across a theological tradition, all but ignored in America, that challenges healthy-mindedness: negative theology, the “apophatic” path.

A primary assumption of this theology is that dejection can inspire a deeper experience of spirit than contentment does. When we are depressed, we often give up hope for solace. But this apathy can open us to a strange power beyond our selfish expectations. This potency is God, unknowable but redemptive, salving our hearts with the love that springs from suffering.

Negation is salvation. Pessimism deepens faith. These compose the religion of the “sick soul,” also developed by James. To the melancholy believer, healthy-mindedness is shallow “because the evil facts which it refuses positively to account for are a genuine portion of reality; and they may after all be the best key to life’s significance, and possibly the only openers of our eyes to the deepest levels of truth.”

When I embraced my sickness, no longer demeaning or ignoring it, I became healthy. No longer demonizing my depression, I accepted it for what it was, and is: a part of me like my lungs or larynx, an organ that has made me who I am, with all of my flaws and virtues.

The world, I realize, is a tragic place, where pain outweighs pleasure. The travails, though, need not cause despair. They can be invitations to a richer life, one of mercy, empathy, and enduring affection.

I recently visited a New York City museum devoted to Ground Zero. A photographer, in commenting on his pictures of the rubble, said that this dreadful place became, as firemen and others searched for the dead, “holy ground.” Terrible loss inspires sacred love. I never want to forget this harrowing yet moving maxim, an article of faith in a world born to fail.