This weekend I perused the first half of Devery Anderson’s The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846-2000: A Documentary History. The book will be released on March 24 and it’s quite a scintillating collection of primary source material about how the temple experience has changed over time.

Some of this was familiar to me, like that not keeping the Word of Wisdom was not necessarily a deal-breaker in getting a temple recommend until the early 20th century (61). And Jonathan Stapley has already posted here about the amazing history of the ritual of temple baptisms for health for living Latter-day Saints. But the book describes many other rather mind-blowing changes I never knew about:

- In the earliest temples, anyone attending to perform an ordinance was expected to make a monetary donation of fifty cents to support temple work (182)

- Mormons sometimes paid other Mormons to go through the temple for them if they were too sick or poor to go, or if they lived too far from a temple (182)

- In deference to some of the Arizona Saints who were too poor to travel to the temple, Pres. Woodruff allowed them to set up an ad hoc sealing room in one of their regular buildings (87-88)

- Temples used to have standing choirs that performed before endowment sessions; sadly, this practice was abandoned in the spring of 1921 (181)

- There were sometimes lectures in the Garden Room (56)

- In 1918 you could receive your endowments as early as age 16 (176)

- President Taylor allowed some people to receive their second anointing in their 20s and 30s, but President Woodruff restricted the ordinance to the aged and the deceased (73, 75). Over time, the ritual became even more restricted, and by 1917 was performed only on Fridays. By the late 1920s, it was reserved for the highest-ranking leaders of the Church, which is where it remains today (xliii-xlv). (Incidentally, I had been a member of the church for years before I even learned of this ritual’s limited continued existence.)

People who have followed with interest the criticism that Mormons have received about performing temple baptisms for Holocaust victims will be interested to learn that it has been church policy for well over a century that members only be baptized for their own family members. Apparently, some things never change:

We must be more strict in enforcing the rule which is here mentioned in regard to heirship in our Temples, and people must not be permitted to follow their whims in being baptized for any and every body whom they may choose to officiate for; and persons should be questioned upon this subject of being baptized for those not of their own kin…. [1887 letter from President Wilford Woodruff to Mariner Wood Merrill, pp. 67-68]

Interestingly, the book demonstrates that Woodruff himself had violated this practice in 1877 when he felt compelled to be baptized for the signers of the Declaration of Independence, as well as John Wesley, Christopher Columbus, and every president up to that point in American history. (p. 41)

Some of the temple policies that have changed over time are ones that would have affected me personally, so of course I read them with particular interest. Here’s one directed toward women whose husbands are not LDS:

The rule of the temple is that a woman who marries outside the Church cannot receive a recommend to go through the temple, because her husband would be very apt to ask her to reveal the temple ordinances and if she refused to do so it would cause contention between them. (1916 letter from Anthon Lund and Charles W. Penrose to Edward H. Snow, p. 172)

It’s certainly great policy to not introduce elements in a marriage that could be contentious, but I’d have an easier time believing that rationale if it had not been enforced by an obvious double standard: LDS men at the time could receive their endowments whether or not their wives were members of the Church. So much for the “it could cause contention” justification.

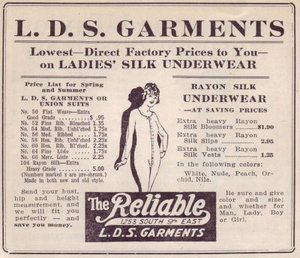

Some of the most interesting sections of the book deal with changes to LDS temple garments, and there are fascinating facsimiles of advertisements from the 1920s, back when private companies could and did produce garments, and they advertised their wares publicly in the Relief Society magazine. For example, the Salt Lake Knitting Store offered a variety of prices and styles–long or short sleeves, ankle length or three-quarter length bottoms–for both men and women. You could pay an additional fifteen cents to have the company mark the garments for you, or you could have them marked right on your body while in the temple (203). In the ad at right for “The Reliable” company, you also had to specify color, which raises the question: what colors were available, other than white?

There’s a terrific story from the oral history of T. Edgar Lyon about going to the temple with the brand-new garment that the First Presidency had just approved in 1923, right before Lyon’s mission, and almost being turned away because the temple workers didn’t know what to make of the newfangled union suit style (203).

Bottom line: this is a mesmerizing compendium of 150 years of primary source material. Take a look.