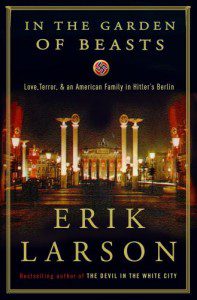

Over the weekend I finished Erik Larson’s In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin, which still ranks in Amazon’s top twenty after almost three months in release. I predict a long (and well-deserved) run for it on the bestseller lists.

Over the weekend I finished Erik Larson’s In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin, which still ranks in Amazon’s top twenty after almost three months in release. I predict a long (and well-deserved) run for it on the bestseller lists.

The book centers around William Dodd, a historian who unexpectedly became the U.S. ambassador to Germany shortly after Hitler’s ascension in 1933. Dodd spoke German fluently, having done his doctoral work there; he was familiar with the culture; and most importantly, he was willing to serve. More than half a dozen people had already turned down the offer, because even the prestige of a European ambassadorial post could not persuade them to enter the belly of Hitler’s beast. Dodd seems to have been about eighth or ninth on President Roosevelt’s list of candidates.

The book does an important service to history in pointing out not just how horrible things were for German Jews in the 1930s, but how rife anti-Semitism was in America as well. This is an ugliness in U.S. history that we tend to gloss over, but Larson’s book shows that some of the era’s most important politicians, statesmen, and captains of industry hated Jews. One visited Atlantic City and found it “infested” with “Jews and Jewesses” on the beach, in the hotels, and in the restaurants.

In this milieu, Dodd comes across as simultaneously enlightened and a prisoner of his age. (Aren’t we all?) His academic training had exposed him to Jewish colleagues, of whom he had a favorable impression, though he never challenged the era’s limited quotas for admission of Jews to the nation’s most prestigious schools.

There was a certain honesty to Dodd’s rise from obscurity to modest fame through intelligence and years of diligent work. Whereas most ambassadors to European nations were born to privilege, slapping each other’s backs at Choate and Philips Exeter, Dodd rose from truly humble farm beginnings and made his own way by getting an education. He lived frugally, walked everywhere, and was not impressed with his own importance. More significantly, he overcame his initial wishful thinking that Hitler’s madness would quickly pass and that no people as strong-minded as the Germans could ever allow their nation to descend into violence and insanity. Dodd’s increasingly outspoken and direct criticisms of the Third Reich made him enemies not just in Germany but also in the U.S. State Department, which recalled him abruptly after four years in service.

The turning point in Dodd’s own transformation from concerned spectator to blunt activist was a weekend of terror in the summer of 1934, when Hitler had hundreds of fellow Nazis massacred because he feared a plot against him. Some of these victims were people Dodd knew and had dined with, and they were often the more moderate voices within the Nazi regime.

A large portion of the book is devoted to the exploits of Martha Dodd, the ambassador’s sexually liberated daughter who accompanied her parents to Berlin. In her early twenties and rebounding from a hasty marriage, Martha threw herself into one affair after another with some of the most powerful men in 1930s Europe, including the head of the Gestapo, a Soviet spy, a German WWI flying ace, a prince, a famous writer, an aide to Hitler, a French attaché . . . who am I forgetting? Oh, yes, the many men she kept on a string back home, including her ex and writers like Carl Sandburg and Thomas Wolfe.

Martha spent much of her first year in Berlin defending Nazism as a vigorous and forward-thinking philosophy that would transform the nation’s economy and put its many unemployed back to work. Maddeningly, she held to this view even after personally witnessing an attack of disturbing mob violence on a civilian. It was only after the Nazis tapped her own phones and perpetrated the atrocities of 1934 that she had cause to change her position. Not the kind to do anything in half measures, she then switched her political loyalties to communism, spying in a rather gadfly manner for the Soviet Union.

In the Garden of Beasts is well-written and fast-paced. Fans of popular history and biography will find much to chew on here. Certainly, professional historians will find elements to quibble about – particularly Larson’s predilection for dramatizing the story by pulling quotes from letters and diaries and using them like imagined dialogue. My own frustration is that the final chapters of the book are so abruptly handled; once Dodd is recalled from Germany, the story becomes a coda, despite the fact that many interesting things happened to the family and the nation after that. I wanted more.

But isn’t that a good criticism in the end—that a reader was left wanting more? Overall, this is a fascinating, albeit unsettling, read. I hope that it serves to raise readers’ awareness of how the unthinkable can and does happen.