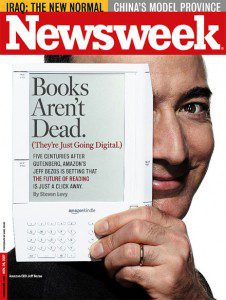

In this morning’s Chicago Tribune, guest writer Aaron Gilbreath, a bookseller at the esteemed indy stalwart Powell’s Books in Oregon, tells publishers that we should “fight dirty” to save our industry from the onslaught of ebooks.

In this morning’s Chicago Tribune, guest writer Aaron Gilbreath, a bookseller at the esteemed indy stalwart Powell’s Books in Oregon, tells publishers that we should “fight dirty” to save our industry from the onslaught of ebooks.

“Why hasn’t America’s publishing industry launched an ad campaign as seductive and aggressive as the Kindle’s? Not to market front-list titles or authors, but to market the paper book form itself? In other words, sell consumers on the exclusive pleasures and qualities traditional books offer that e-books cannot. That’s exactly what Kindle’s TV commercials have been doing, saying here’s what we can do that regular books can’t.

Kindle ads are ingeniously engineered. Through a string of images (Kindle in your back pocket; Kindle withstanding licks from a dog), Kindle advertises itself as thinner, lighter and more durable than a book. And with a number of memorable taglines like “Books in 60 seconds,” Kindle boasts its unique advantages: 900,000 titles available on Amazon; rapid downloads; able to hold an entire library in the space occupied by a single paperback.

How can paper books compete with that? If traditional book publishers want to survive, then their marketing departments better think of a way. And fast.”

The editorial seems to take it for granted that ebooks are putting publishers out of business. That’s wildly incorrect. Publishing is hardly in peachy shape, but that’s not the fault of ebooks in general or the Kindle in particular. Myriad other factors are driving our industry to innovate or die, including the following:

1) the “cult of the free,” or the growing expectation among consumers that books will be cheaper than their production costs or even free;

2) the ubiquity of used print books that are so inexpensive and readily available online that there is rarely a reason for consumers to buy a new print book unless it has just been released;

3) the demise of traditional brick-and-mortar bookstores;

4) the high cost of returns from stores and distributors (all of which occur at publishers’ expense);

5) the superiority of rapid online research sites to print reference works; and

6) the explosion of fee-for-service self-publishing, which will make soon traditional publishing obsolete. (That’s what should keep publishers awake at night.)

Not only are ereaders not responsible for publishing’s dire straits, I’d argue they may be part of the industry’s tenuous salvation. Consider these factors:

1) With ereaders as they are currently configured, every book sold is a genuine sale. Publishers don’t have to pay to warehouse books, ship them, or take them back from stores at our own expense if they don’t sell. There are no returns to speak of.

2) Publishers can save about 20% of our production costs on ebooks. In an industry with such razor-thin margins, that’s huge.

3) There is no such thing as a used ebo0k. In other words, the print used book sales that are now killing publishers don’t exist at all on the Kindle; with the Nook, one loan is permissible for each book, and that’s it.

4) Right now, most book contracts stipulate that authors earn a lower royalty from ebooks than print books. This will likely change (and, speaking as a publisher who is also an author, it should), but at the moment, most publishers take home a higher percentage of every electronic book sale than we do from every print book sale.

(What’s really a problem for publishers — and for authors — and for booksellers — is that with public libraries now forging alliances with ereaders so that borrowers will be able to download ebooks directly to their devices from their local library without ever having to leave their own home, no one in his right mind will want to buy a book anymore. But that’s another post entirely.)

So, to answer the editorial’s central question — why publishers aren’t aggressively hawing the print medium in expensive ads around the nation — it’s because it’s not in our best interest to do so.

It also does not benefit the average reader. I’ve been a book lover all my life, and will continue to be a biblioholic in whatever medium is close at hand, but I can see no inherent advantage that print has over digital, and plenty of advantages that digital has over print. If these publishers’ imaginary ads are merely going to rehash nostalgic arguments about how print “smells like a real book” or how “you can’t curl up with a Kindle” (which is perfect nonsense), then that’s hardly the progressive, innovative approach that this bookseller thinks is necessary to save publishing from itself. It is in fact precisely the opposite.