In July, I attended my first Muslim wedding, and it was an unforgettable occasion. The bride has been a good friend of mine for almost a decade, and in that time I’ve heard about the ups and downs of halal dating and the quest for the right mate. She came close to the altar—make that the canopy—a couple of times, but it never quite worked out. She wanted to be a good Muslim and please her family with an arranged marriage. But she also wanted to be an American—and a feminist—and marry to please herself.

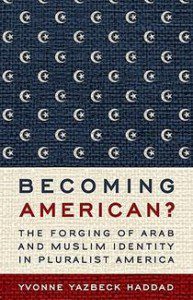

I was thinking about my friend the whole time I read Yvonne Haddad’s brief but fascinating new book, Becoming American? The Forging of Arab and Muslim Identity in Pluralist America, which I review here as part of a Patheos.com rountable discussion about the book and about Islam in America.

I saw my friend’s story in many places throughout Haddad’s chronicle of Muslims in America: her parents were part of the South Asian “brain drain” of the late 1960s and early 1970s, which the book identifies as a critical shift in Muslim American immigration (4). Her father, a successful professional, became an even more successful businessman, then gave back to the community by founding a school and supporting a legion of charities. My friend and her siblings mirrored many of the hopes of second-generation immigrants: they were encouraged to be diligent in school and to pursue high-profile careers, but also remain closely tied to family and tradition.

That can be a lonely road. For example, my friend is among the estimated 80% of Muslims in America who are “unmosqued” (my new word du jour; see p. 30). For her I think this is partly because it’s hard for an assimilated American woman to find a place in the mosque, even though as Haddad points out, the mosque itself is changing in its American iteration. The role of the imam is morphing into something more like a pastor, and many U.S. mosques now invest their zakat (charitable giving) in serving the needy right here in America, rather than sending those dollars back to a “home country” as previous generations of Muslims were likely to do (24).

I also saw her family’s experience in the political aspirations of American Muslims, and their allegiance to the Republican Party in the Bush-Cheney years (68). Drawn by powerful promises of a seat at the table, Muslim voters, including my friend’s parents, supported Bush with not just votes but large donations. But the story doesn’t end there. Like some other Muslim Americans, my friend’s brother—a rising young politician himself who was quite literally born on the Fourth of July—recently defected from the Republican Party. When I asked him why, he said that one reason was how disappointed he became this time last year when many conservatives, especially members of the Tea Party, so vociferously attacked the idea of the “Ground Zero Mosque” (an oft-perpetrated misnomer), even to the point of denying the proposed building’s constitutional right to exist. So even though he is still a Bush fan and says Bush’s lifting of sanctions against Muslim nations helped result in 2011’s “Arab spring,” he’s also disappointed that the Republican Party post-Bush has become increasingly xenophobic.

In all, my friend’s family beautifully illustrates the tensions that Haddad touches on in her book: “What does it mean to them to be an American? Do they want to be American or hyphenated-American? Do they think of themselves as Muslims living in America . . . or do they think of themselves as Americans who happen to be Muslims?” (96)

My friend’s joyous wedding showed the answer: Muslims can be—and are—both/and, not either/or. My friend found her husband in the both/and way, thanks to a Muslim dating website that hewed to tradition while allowing for individual choice and some old-fashioned romance. And at the wedding itself, we boogied down to Pakistani favorites I’d never heard before, as well as to the upbeat stylings of “Celebration” by Kool & the Gang.