A couple of weeks ago when I was in Salt Lake City I had the privilege of sitting down with two historians who work with the Joseph Smith Papers project, an ambitious documentary history effort that’s seeing another volume in print today. If you’re interested in primary sources about the founding of the Relief Society, original letters from Emma Smith, or information about Nauvoo-era teachings on baptisms for the dead, the volume is worth exploring. It’s available at Deseret Book, some independent booksellers, or here at Amazon.com. –JKR

Interviewees:

Matthew Grow, Director of Publications at the Church History Department

Robin Jensen, Project Archivist for the Joseph Smith Papers

Can you explain the Joseph Smith Papers project in general?

Grow: The goal of the Joseph Smith Papers project is to publish every extant document owned, created, or authorized by Joseph Smith. Eventually there will be about 20 volumes of the Joseph Smith Papers in print, and even more material available online. The website will be comprehensive in that it contains every document that falls into those three categories.

We have done four so far, and [on November 15] the second volume in the journal series will come out. The first volume was 1832-39 journals, while the second takes us into the Nauvoo years, 1841-43. We’ve also done two volumes in our Revelations and Translations series.

What is special about this particular volume?

Jensen: Historians want to understand Joseph Smith as a person, but he shied away from creating his own records, which means we get very little glimpse of his personality. The instances where you capture his voice are really exciting. The first journal of 1832-33 is in his own hand, and very often he just slips into prayer. Then later in Nauvoo where we have imperfect and incomplete records of his sermons, even then Joseph really shines out and you get a glimpse of his charisma and why people gravitated towards him.

Grow: The Joseph Smith papers are not only a record of Joseph Smith, but of how early Mormonism grows up. You see in the early documentary record how Joseph is able to coalesce a following.

We expect this volume and the next two to have the widest interest – this one has the beginnings of the Relief Society, as well as the growing opposition [to Mormonism]. It talks about Joseph Smith’s legal troubles in Illinois. The two volumes next year are the histories that Joseph Smith wrote or dictated, including a short personal history that he wrote in 1832, or that the earliest historians wrote.

What about Smith’s revelations? How do you present them in the published volumes?

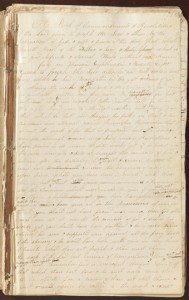

Grow: In the early days of Mormonism there were two record books that scribes used to write down Joseph Smith’s revelations. They were [first] written on scraps of paper and then transcribed into these record books. Since those revelations are so central to early Mormonism, we wanted to present them as they were. Every left side page is the image of that document, and the right hand is the transcription. The revelations were seen in some respects as working documents. Joseph felt the need to revise them at times. We’ve identified the edits on the page, and also who made the edits.

Jensen: We had three different experts go through the documents independently to identify the writing, and I collated all the work. In some cases, there are obvious clues. Sidney Rigdon had a tail on all of his carats, for example. Ink analysis can also help, if you can identify that on a page. We’ve brought on multi-spectral imaging and ultraviolet light. Whatever technology we can bring to the table, we use.

What has surprised you in your work so far?

Grow: The most important thing has been the manuscript revelation books. The earliest revelation book, created in 1831, was basically unknown to historians until it was provided to the Joseph Smith papers from the vault of the First Presidency around 2007.

Jensen: This book, previously unknown to contemporary historians, shows us the way that the revelations were prepared for publication.

Grow: One of the takeaways for scholars is this question of the editing of the revelations. This shows us the way in which that happened, the extent of the involvement of Joseph Smith, and how he viewed these revelations: That they were not set in stone, but could be changed according to later circumstances and later inspiration. At least for some of the revelations, they’re seen as working documents.

Who is the primary audience for these published volumes?

Jensen: The Joseph Smith Papers project is a scholarly endeavor, written for other scholars to pursue their own history. I hope this effort prompts scholars to take the revelations more seriously. We want to present them in as much transparency and accuracy as we possibly can.

What’s the timetable for the overall project?

Grow: There will be about 20 volumes total. We hope to do two a year and finish with the project around 2020. That’s a very ambitious schedule. We have three teams of people – scholars, a web team, and the production editing team. We are the publisher of the Joseph Smith papers, which means we do everything from source checking in house. We have about 25 people working in-house.

Do you ever get accused of having an agenda for this project?

Jensen: We get asked about our biases coming into play. So we have a national advisory team that consists of Stephen Stein, Harry Stout, Sue Purdue, and Terryl Givens. [Ed: Of these, only Givens is LDS.]

Grow: Our response is to publish books of the highest quality that meet the highest standards, and to publish absolutely everything—documents that put Joseph Smith in a favorable light, and docs that don’t.

The church history department has never been more open. Everything is accessible with certain restrictions, and those restrictions are around 1) material that we consider “sacred.” That basically refers to temple ordinances. 2) Material that is private, which could violate privacy laws. And 3) material that is confidential, like disciplinary councils or meetings of the highest church councils. Excommunication proceedings are private after the Joseph Smith era.

There’s a tremendous archive of oral interviews here, and it’s an archive that’s expanding all the time. We’re in a moment of international outreach, where we are trying to institutionalize and decentralize the history gathering around the world. Each of the international areas of the church now has a historian called in that area. In Brazil, the history person would be charged with gathering documents, taking oral interviews, and archiving them.