I was 23 and in divinity school when I converted to Mormonism. You can imagine that it was an unexpected choice for someone studying to become a pastor. I was perhaps the most surprised of all; God does crazy stuff to folks sometimes.

I told very few people about it while I was in school, but one such conversation stands out vividly in my mind. My gentle, kind friend Tom (not his real name) and I were having lunch on the balcony of the Mackay Center at Princeton Theological Seminary’s cafeteria when I dropped the bombshell that I had recently been baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

You read in fiction about people’s jaws dropping, but I think the only time I ever saw it happen in real life was when Tom stared at me from across the table.

He let me talk for a time about my experiences and then told me that when I had first given him the news, his gut reaction was, “This woman has joined a cult! I have to say something that will save her!” Since he had grown up in a very conservative church, he was worried for my soul.

But the impulse that won the day was, “This woman just came out to me.”

You see, the summer before, Tom had visited me and my husband to announce to us that he was gay. He was afraid to tell the other people in our group Bible study because he wasn’t sure how they would react. He knew we would be supportive, and I dearly hope we were. Who wouldn’t love Tom?

So that was the history that lay between us as I confessed my own situation to him that day at lunch. We weren’t all that different, Tom and I; we were both in the closet in some way, afraid of revealing a key part of ourselves, afraid of rejection. Both of us have had rather amazing journeys since then, and we are both “out,” whether regarding religion or sexual orientation. There is wholeness and openness to our lives now.

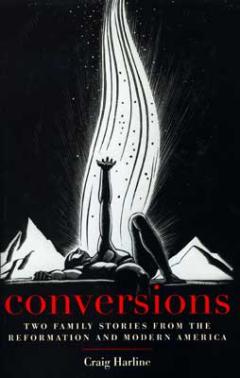

I’ve thought often of this story over the last few weeks as I read the magnificent book Conversions: Two Family Stories from the Reformation and Modern America by historian Craig Harline. I had read Harline’s wonderfully written cultural history of the Sabbath a few years earlier, so I knew I would be in for a treat, but I was surprised by how personally the new book affected me.

Conversions expertly braids three different true stories: There’s Jacob, a 17th-century Dutch youth who breaks his family’s collective heart by throwing off the Dutch Reformed Protestant religion and aligning himself with Catholicism, which his father regarded as “the whore of Babylon.” There’s Michael, a young middle school teacher in 1970s California who becomes estranged from his parents when he unexpectedly converts to Mormonism — and then risks their rejection a second time when he realizes he is gay. And then there’s Harline himself, who explores his own Scandinavian ancestors’ conversions to Mormonism and the hardships and disconnections they endured as a result.

I think it is very difficult for historians to straddle a balance between sticking close to primary sources and allowing historical subjects to exist in their own era even while imagining the very human — and timeless — emotions that the historical subjects must have been experiencing. One of the things I love most about this book is how Harline is able to do precisely that. We never lose sight of the fact that these are all-too-human stories, with family dynamics we will recognize and mixed motivations at every turn.

One of the other things I love most about the book is how Harline extrapolates larger issues of religious (and other) conversions from these stories. How are identities formed? What, ultimately, prompts people to risk significant ruptures to follow what they perceive as religious truth or a more authentic identity? In the end, Harline finds fluidity in people’s emerging self-definitions. There are no “converts,” full stop, in any faith. There are those in the process of converting and those in the process of disaffiliating. And although the process of deconversion is every bit as fraught with potential heartache as conversion, many if not most people go through it at least for a spell; for example, Harline cites one 1979 study that found that 78 percent of Mormons had dropped out of activity for at least a year (p. 139).

As the subtitle suggests, these are family stories, not just individual ones. Readers feel the mixture of anger and heartbreak experienced by Jacob’s sister Maria as she wrote him long letters defending the childhood faith he had jettisoned and urging him to reconcile with their parents. Readers may also want to swat Jacob, as I did, for continuing to rub his family’s noses in his self-righteousness and conviction that their religion was evil. And this leads to one of Harline’s conclusions — completely true to my experience — that the families “who managed to accept family members of rival faiths emphasized what they had in common rather than what they did not.” (p. 248)

If your life has been affected in some way by conversion or deconversion, either your own or a family member’s, read this book. It’s fresh, and insightful, and wonderfully human.