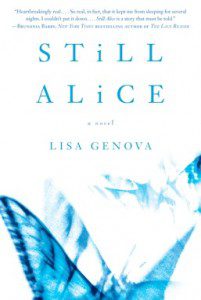

This month my book club read Still Alice, neuroscientist Lisa Genova’s haunting novel about a Harvard cognitive science professor who discovers, at age 50 and the height of her career, that she is succumbing to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

This month my book club read Still Alice, neuroscientist Lisa Genova’s haunting novel about a Harvard cognitive science professor who discovers, at age 50 and the height of her career, that she is succumbing to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

My take on the book was that I learned a tremendous amount about the disease but that it didn’t quite cohere as a novel. There are some technical problems with the storytelling, from the small cliches (describing a character via her reflection in the mirror) to more major glitches (climaxing with a sermonic neuroscience lecture that goes on for pages). There are some small issues with narration; most of the novel uses limited omniscience but then there are small passages that assume total omniscience on the part of the narrator. It felt like the kind of novel that was written by a new writer of amazing raw talent who needed an editor to hone the voice and attend to small technical details.

Having said that, what a powerful story. I think all of us in book club were rooting for Alice as she underwent the painful journey of defining herself by more than just her career. There are some unforgettable scenes. For me, having worked as a college professor, the most poignant sequence is when Alice goes to her Harvard class but then forgets that she is the teacher and not a student. She waits for the professor alongside the students in the class, increasingly annoyed at the teacher’s absence and oblivious to the uncomfortable stares of the students who wonder just what in the world is going on with their professor, whom they see sitting right there acting weird. Alice eventually gives up and walks out, declaring she has better things to do than wait all day for a no-show.

Several of us also wanted to strangle Alice’s husband John, who attacks the problem first by complete denial and then by seeking the most aggressive therapies in existence . . . but can’t bring himself to love his wife through this painful descent. He wants to define her as his brilliant superstar spouse, not as this dependent patient whose needs will only grow more insistent. As readers we certainly had sympathy for him — and felt that the story portrayed a very realistic situation of family members’ varying abilities to cope — but did I mention the strangling part? Also a factor.

In all, this was a worthwhile read. If it tends too far in the direction of a didactic “issue” novel at times, its heart is definitely in the right place. Moreover, its central message — that Alice is, despite and perhaps even because of her disease, “still” Alice — resonated with me deeply.