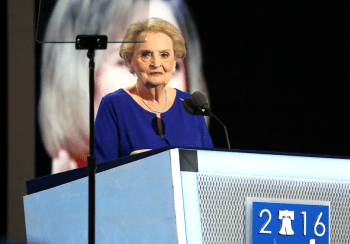

Madeleine Albright, the first woman US secretary of state, who helped steer Western foreign policy after the Cold War, has died of cancer at 84 years old. Her family announced her death in a statement Wednesday.

Albright was a crucial figure in President Bill Clinton’s administration. She first served as US ambassador to the United Nations before becoming the nation’s top diplomat in his second term. She championed expanding NATO, pushed for the alliance to intervene in the Balkans to stop genocide and ethnic cleansing, sought to reduce the spread of nuclear weapons, and advocated human rights and democracy across the globe.

Born Marie Jana Korbelova, the daughter of a Czechoslovakian diplomat, in Prague in 1937, Albright escaped then-Czechoslovakia with her family days after the Nazi invasion. Her experience growing up in communist Yugoslavia and then fleeing to the US made her a lifelong opponent of totalitarianism and fascism. She was raised Roman Catholic, though she later converted to Episcopalian, and learned later in life about her family’s Jewish heritage.

Albright graduated from Wellesley College in 1959 and was married to Joseph Albright from 1959 until 1983 when they divorced. They had three children, twins Anne and Alice in 1961 and Katharine in 1967. She attended Columbia University for her master’s degree and Ph.D., which she completed in 1976 before launching a decades-long career in government service and foreign affairs work under different Democratic politicians and causes.

She was a face of US foreign policy in the decade between the end of the Cold War and the war on terror triggered by the September 11, 2001, attacks, an era heralded by President George H.W. Bush as a “new world order.” In Iraq and the Balkans, the US built international coalitions and occasionally intervened militarily to roll back autocratic regimes. Albright, a self-identified “pragmatic idealist” who coined the term “assertive multilateralism” to describe the Clinton administration’s foreign policy, used her experience growing up in a family that fled the Nazis and communists in mid-20th century Europe to shape her worldview.

Perhaps most notable were her efforts to end violence in the Balkans, and she was crucial in pushing Clinton to intervene in Kosovo in 1999 to prevent a genocide against ethnic Muslims by former Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic. She was haunted by the earlier failure of the Clinton administration to end the genocide in Bosnia.

The breakup of communist Yugoslavia into several independent states, including Serbia and Montenegro, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia, in the 1990s generated savage bloodshed unseen on the continent since World War II. The term “ethnic cleansing” became synonymous with Bosnia, where Serb forces loyal to Milosevic tried to carve out a separate state by forcing out the non-Serb civilian population.

The Clinton administration did not intervene until the massacre at Srebrenica in 1995, when Serbs killed 8,000 Muslim men and boys, which led to the US-brokered Dayton Peace Plan. But when Milosevic then tried to move his ethno-nationalist plan to Kosovo, the Clinton administration gathered a coalition to stop him doing there what he had gotten away with in Bosnia.

Albright was known for wearing brooches or decorative pins to convey her foreign policy messages throughout her career. When she found out that the Russians had bugged the State Department, she wore a large bug pin when she next met with them. When Saddam Hussein referred to Albright as a snake, she took to wearing a gold snake pin; when she was called a witch, she proudly brandished a miniature broom.

Following her term as secretary of state, Albright served as chairwoman of the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs in Washington from 2001 to her death, and she taught at Georgetown University. She was also a prolific author, penning several books, including a memoir in 2003 entitled “Madam Secretary.” She also worked in the private sector for a time.

In 2012, Albright received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama, who said her “toughness helped bring peace to the Balkans and paved the way for progress in some of the most unstable corners of the world.” Asked by USA Today in August 2020 how she defined courage, Albright replied, “it’s when you stand up for what you believe in when it’s not always easy, and you get criticized for it.”