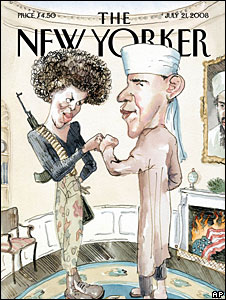

The Immanent Frame, the Social Science Research Council’s blog on religion, secularism, and the public square, has a post up claiming that the current war of words between Focus on the Family’s James Dobson and supporters of Barack Obama may be inflating Dobson’s influence and furthering the myth of the evangelical monolith:

The Immanent Frame, the Social Science Research Council’s blog on religion, secularism, and the public square, has a post up claiming that the current war of words between Focus on the Family’s James Dobson and supporters of Barack Obama may be inflating Dobson’s influence and furthering the myth of the evangelical monolith:

Though the Dobson/Obama debate is itself worthy of analysis, it is even more useful as a Rorschach test for contemporary evangelicalism. Though pundits and social scientists regularly talk about “the evangelical vote,” the contemporary controversy calls attention to something historian Nathan Hatch observed as far back as 1990, namely that “there is no such thing as evangelicalism.”

As a co-founder of the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals, Hatch did not mean to suggest that there were no religious leaders and organizations flying the evangelical flag. Nor did he wish to minimize the impact of revivalistic Protestantism in American history. What Hatch meant is that evangelicalism is too heterogeneous, theologically diverse, and institutionally pluriform to fit comfortably under a single label. This point was amplified by D.G. Hart in Deconstructing Evangelicalism, a book that traces the invention of the category by scholars, pollsters, and movement leaders. More recently, the journalist Christine Wicker has questioned the claim that conservative Protestantism is a unified, vital movement in The Fall of the Evangelical Nation, noting the over-counting of sheep by the Southern Baptist Convention and the small percentage of conservative Protestants who embrace a rigorous definition of evangelicalism.

The Obama/Dobson debate gets at the same issue by exposing the myth of the evangelical vote. The deep divisions in the evangelical house can be seen in the contrasting reactions to the controversy, suggesting that it may be more accurate to speak of multiple evangelicalisms, rather than a monolithic movement.

There’s been a lot of ink and airtime expended this election cylce on debunking the myth of the evangelical vote. Much if it has come from evangelicals themselves, sick of always being portrayed as Republican activists, especially in the days since the 2004 election. But amid all the current attempts to debunk the myth of the monolithic evangelical vote, it’s important to remember that evangelicals have voted as a bloc in modern elections, unlike other religious groups, like Catholics or Mainline Protestants.

That was especially true in the 2004 election, when 78-percent of self-identified evangelicals pulled the lever for George W. Bush. If that’s not a bloc, God-o-Meter doesn’t know what is.

Of course, the 2004 election was unusual. Bush got a greater share of the evangelical vote than any candidate on record. Nonetheless, the pattern of lopsided evangelical support for Republican candidates dates back a couple of decades. The 1980 election, the first after Jerry Falwell founded Moral Majority, saw evangelicals break two to one for Reagan. In 2000, 68-percent of them supported Bush over Al Gore.

That’s not to say that there’s no political diversity among evangelicals. And lefty activists like Jim Wallis have gotten lots of attention for their wing of the evangelical movement. But it’s beyond dispute that evangelicals are a Republican voting bloc.

There’s no way evangelicals will become swing voters this year. They’ll break again for the Republican presidential nominee in November. The question is whether Barack Obama could make modest enough inroads among them, or if John McCain will provoke enough of them to stay home, to make the Democrats’ job easier. That could happen. But it doesn’t mean evangelicals aren’t a cohesive voting bloc. They are, and one of the nation’s most formidable.

5