While the rest of the world buried its collective nose in Harry Potter last weekend, I spent my time reading early Christianity. It proved a tough call: The fate of Hogwarts or the Roman Empire? I chose Constantine over Voldemort.

While the rest of the world buried its collective nose in Harry Potter last weekend, I spent my time reading early Christianity. It proved a tough call: The fate of Hogwarts or the Roman Empire? I chose Constantine over Voldemort.

I am not a total geek, but I am writing a new book on church history for progressives. One problem of classical liberalism was its rejection of tradition and the inability to ground its vision in Christian history. The past was seen as imperfect, full of injustice and mistakes, and incomplete understandings of nature, humanity, and God. Thus, liberal Christians embraced the future as the major arena of God’s activity—tending to privilege what is new over what was old.

The past? What does that have to do with pressing issues today?

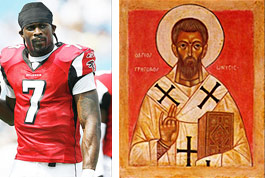

Well, take the allegations against Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick for animal abuse and dog fighting, for instance.

One of the texts I re-read this week was On the Soul and the Resurrection (c. 380 C.E.) by Gregory of Nyssa, a theologian in the Eastern Christian tradition. The manuscript takes the form of a dialogue between Gregory and his sister, Macrina. In it, she instructs her brother on the nature of creation. Macrina argues that human beings and “irrational animals” share common gifts from God, the ability to perceive and passions. What separates human animals from “irrational” ones is the capacity of free will, part of human ability to discern and choose. Thus, humans are given the responsibility to care for animals, as irrational animals are subject to human free will.

Gregory, quoting his sister, goes on to say: “For when reason does not control the impulse which naturally lies in them, the fierce animals are destroyed by anger because they fight among themselves.” Likewise, human beings who fail to discern and act upon what is good will be consumed by irrational sin. Gregory directly links human treatment and care for animals to acts of human violence, and implicitly develops a Christian theology of creation care.

The dialogue between Gregory and Macrina is one of the gossamer threads in Christian tradition. Unlike Soul, much of Christian theology emphasized distinctions between humans and animals, rather than stitching connections between aspects of creation (indeed, Macrina even develops a connection between humanity and plant life). Dividing creation into superior and inferior ranks served as an excuse for rampant injustice on the part of Christians toward the rest of creation—and, sadly enough, toward other human beings (for example, women denied the priesthood or race-based slavery). What if instead of organizing humans and animals into hierarchical ranks, Christians had theologically developed the commonality of creation so tantalizingly suggested in the fourth century?

In her recent book, The Frontiers of Justice, philosopher Martha Nussbaum points out that Jews and Christians practice ethics of compassion for animals, but that these ethics are incomplete—that “cruel and oppressive treatment of animals raises issues of justice.” Nussbaum insists, “not only that it is wrong of us to treat them that way, but also that they have a right, a moral entitlement, not to be treated in that way. It is unfair to them.” (Emphasis hers.)

The Michael Vick allegations revolt good people, those who believe it is wrong for a person to treat animals viciously. If proved true, Vick failed to meet even the basic Christian requirement to employ reason and free will to care for his dogs. But this case pushes further: What of the animals? What are the fundamental rights of the dogs to happiness and life? How can those rights be guaranteed and protected? (Interestingly enough, India’s highest court recommended a course for the construction of animal rights in 2000.) And how do religious people generate a vision for animal justice from their theological traditions?

Some Christians may think that we have fallen so short on practices of human justice that to consider justice for animals is beyond our capabilities. But Nussbaum insists that “truly global justice” requires constructing a decent life for “other sentient beings with whose lives our own are inextricably and complexly intertwined.”

Of course, that is pretty much what Macrina pointed out to her brother, Gregory of Nyssa, in 380. Maybe the doing of justice just requires going back and paying attention to gossamer threads.

Diana Butler Bass (www.dianabutlerbass.com) holds a Ph.D. in church history from Duke University and is the author of the award-winning Christianity for the Rest of Us: How the Neighborhood Church is Transforming the Faith (Harper, 2006).

More from Beliefnet and our partners