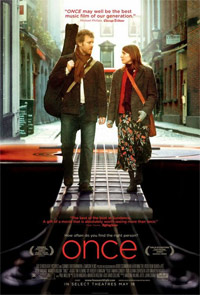

A little film called Once has been winning the hearts of cinemagoers for a couple of months now, with even Steven Spielberg saying that it has given him “enough inspiration to last the whole year.” I finally saw it earlier this week and was moved and entertained by a beautiful little story of love and music on the streets of Dublin. But beyond the pleasure of watching natural performances, hearing great songs, and feeling connected to two lonely people trying to find happiness, Once also tells a story of economic injustice. The central characters are a vacuum repairman with a profound song-writing style, and a Czech immigrant worker who sells roses to tourists on the city streets and plays the piano and sings with heartbreaking fragility. She lives in a house with other immigrants, sharing one room for recreation, cooking, and sleeping, and is used to being treated with disdain. Once is one of the first films to take seriously the condition of the people known as the “new Irish”—the immigrants (primarily from Eastern Europe and Africa) who have made their way to the land of saints and scholars in the hope of being able to send money home to their relatives, or to make a new life for themselves.

A little film called Once has been winning the hearts of cinemagoers for a couple of months now, with even Steven Spielberg saying that it has given him “enough inspiration to last the whole year.” I finally saw it earlier this week and was moved and entertained by a beautiful little story of love and music on the streets of Dublin. But beyond the pleasure of watching natural performances, hearing great songs, and feeling connected to two lonely people trying to find happiness, Once also tells a story of economic injustice. The central characters are a vacuum repairman with a profound song-writing style, and a Czech immigrant worker who sells roses to tourists on the city streets and plays the piano and sings with heartbreaking fragility. She lives in a house with other immigrants, sharing one room for recreation, cooking, and sleeping, and is used to being treated with disdain. Once is one of the first films to take seriously the condition of the people known as the “new Irish”—the immigrants (primarily from Eastern Europe and Africa) who have made their way to the land of saints and scholars in the hope of being able to send money home to their relatives, or to make a new life for themselves.

It is rare to see these people portrayed as honestly as Once does—this is a humanized vision of people who I often walk past in my own hometown of Belfast. Artists and lovers disguised as rose sellers, manual laborers, and street-magazine hawkers. My conscience was challenged by this movie—to imagine the lives of others beyond the stereotypes that the powers that be tend to reinforce. The day after seeing Once I found myself on an inter-city bus in California and was further reminded of the often-difficult situations of those whose economic circumstances make reliance on public transportation a necessity. A journey that takes three hours by car eventually took nearly four times as long. It included very uncomfortable conditions, intimidating conversations, extremely long delays, and no accurate information for customers, many who were already feeling tired and more than a little powerless. One example should suffice to illustrate this: While in transit I met a woman who had traveled from Canada to visit her ailing brother, and partly due to the chronic tardiness of the bus company, she did not arrive in time to say goodbye. Insult piled on injury on her return trip, as she had to stand in line for several hours to ensure a place on a bus that finally left Los Angeles two hours late.

I contacted the media representatives of the bus company (which I’ll not name, but let’s just say it’s a big one, and has a picture of a fast-moving canine on the side of its vehicles) to raise questions about the way their customers appeared to be treated like cattle. They told me that they train their employees to provide information and assistance as necessary, and that they inform customers when delays are to be expected. Yet neither of these things happened on Tuesday; other customers told me that this was their all-too-common experience. The fact that this company has a near-monopoly on transporting the poor in America may mean that it does not feel the need to do much to respond to complaints. There are many comments on consumer affairs Web sites by people who have never received a response to the questions they addressed to this company. It is not difficult to believe that if everyone with a complaint told the company that they were writing an article about its service they might receive a better standard, one that at least comes close to offering more than a modicum of human dignity to passengers and employees alike. I came away from this encounter thinking that to deny dialogue to disrespected customers is only one of the ways in which the poor are downtrodden in our society. The poor are easy to ignore when they are made invisible to the powerful; it’s for this reason that I recommend that everyone should both take an inter-city bus trip (and tell the company what they think about the service), and watch Once, for it is not just a beguiling love story, but a powerful reminder of how easy it is to hide from poverty if we want to ignore it.

Gareth Higgins is a Christian writer and activist in Belfast, Northern Ireland. For the past decade he was the founder/director of the zero28 project, an initiative addressing questions of peace, justice, and culture. He is the author of the insightful How Movies Helped Save My Soul and blogs at www.godisnotelsewhere.blogspot.com

Gareth Higgins is a Christian writer and activist in Belfast, Northern Ireland. For the past decade he was the founder/director of the zero28 project, an initiative addressing questions of peace, justice, and culture. He is the author of the insightful How Movies Helped Save My Soul and blogs at www.godisnotelsewhere.blogspot.com

More from Beliefnet and our partners