I couldn’t sleep after watching last month’s Republican presidential forum on August 5. I was especially disturbed by the intersection of two statements made by Colorado Rep. Tom Tancredo. Perhaps because he is not in the top tier of Republican candidates, it was easy to consider his statements marginal and negligible, but I believe – completely apart from his presidential aspirations – that his statements should get us thinking, especially those of us who are, like Rep. Tancredo, known as evangelical Christians.

I couldn’t sleep after watching last month’s Republican presidential forum on August 5. I was especially disturbed by the intersection of two statements made by Colorado Rep. Tom Tancredo. Perhaps because he is not in the top tier of Republican candidates, it was easy to consider his statements marginal and negligible, but I believe – completely apart from his presidential aspirations – that his statements should get us thinking, especially those of us who are, like Rep. Tancredo, known as evangelical Christians.

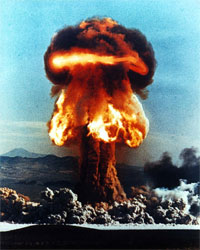

The representative said that as president he will tell Muslim extremists that if they attack the United States with nuclear weapons, he will respond by bombing Medina and Mecca.

Although the State Department has called his statement “reprehensible” and “crazy,” a few days later Tancredo offered what seemed to be further justification for his statement. He explained, according to Iowapolitics.com, that a promise to destroy Muslim holy sites “is the only thing I can think of that might deter somebody from doing what they would otherwise do. If I am wrong, fine, tell me, and I would be happy to do something else. But you had better find a deterrent, or you will find an attack.”

Although none of the other candidates in the forum seemed to agree with Tancredo, they all seemed eager to prove themselves most ready to keep nuclear weapons “on the table” and to present themselves as “strong on national defense,” which now may turn out to mean “committed to pre-emptive war theory over just war theory.”

Tancredo’s threat was all the more disturbing to me in light of something he said later in the same forum when asked about his most significant mistake. He replied, “… it took me probably 30 years before I realized that Jesus Christ is my personal Savior.”

Of course, this confluence of aggressive rhetoric with professions of evangelical faith is not unique to Tancredo. For example, a recent editorial by a popular and award-winning religious broadcasting personality had a similar theo-combative tone. Christiane Amanpour’s recent “God’s Warriors” series on CNN brought a number of other similar voices to our attention.

Democratic candidates are certainly not immune to this impulse to flex their combat credentials, evidenced by recent sparring between leading candidates. We can hope, in the midst of a heated campaign season, that responsible theologians and religious leaders will acknowledge the 800-pound gorilla in the room, and engage in a needed public conversation about faith, politics, and war. This life-and-death conversation can’t be left to politicians and media pundits alone. A recent New York Times article by Mark Lilla raises some key issues to be addressed in this needed dialogue.

A few evangelical voices have spoken out strongly against this ongoing inflation in aggressive rhetoric, but in my mind, remarkably few. Some, no doubt, do not want to dignify extreme statements with a reply. A surprising number, though – readily searchable in the blogosphere – are actually saying “amen.”

As I mull all this over in the middle of the night – running the bases from angst to depression to prayer and hope – I can’t help but think of the oft-heard complaint regarding moderate Muslims: Why don’t they stand up and speak out more vociferously against the violent rhetoric of Muslim extremists? If their religion truly is peaceful, why don’t they speak up for peace more passionately? This may now become a “plank and splinter” issue (Matthew 7:3-5) for evangelical Christians – not to mention Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, mainline Protestants, and others — raising questions like these:

At what point does the rhetoric of fellow evangelicals (or Roman Catholics, etc.) become extreme enough to elicit from evangelical leaders the kind of loud and public response we wish moderate Muslims had been giving regarding Muslim extremists? Which leaders are speaking out, and which aren’t?

Does Rep. Tancredo’s recent statement qualify as excessive? Why or why not? If not, what would push it over the line?

How can evangelicals in particular and Christians in general who don’t agree with this kind of rhetoric respond constructively – and in ways that will be heard as widely as the original statements?

How do thoughtful Christian theologians respond to this kind of rhetoric? On what basis do they justify or reject this kind of rhetoric and the biblical interpretation used to defend it? Where and how can concerned seminary professors and other scholars speak up and be heard?

What will be the predictable effects of this kind of rhetoric on the public perception of “evangelical” and “Christian” – among younger Christians in America? Among non-Christians? Among Muslims here and around the world?

What forms of deterrence can be explored that are more in line with the life and teachings of Jesus? In other words, if we reject both Rep. Tancredo’s approach and the opposite approach of passivity, what could a creative, nonviolent, responsible third way look like?

How can we learn from leaders like Dr. King and Desmond Tutu to stir people to be as passionate about active peace-making as a solution to war as others are about war-making as a solution to war?

If “holy war” rhetoric is indeed escalating in a vicious cycle among Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others, what will be the predictable outcome? How can concerned religious leaders work for a new kind of dialogue and in so doing help chart a more peaceable course for their faith communities?

How can American evangelicals, and Christians in general, escape our echo chamber and begin to listen to the wise voices and concerns of their brothers and sisters around the globe – as Ryan Rodrick Beiler’s recent posting invited us to do?

These questions are worth raising, because in the election year ahead, I expect there will be a lot more of this kind of “God’s warriors” rhetoric to respond to. Maybe Rep. Tancredo’s proposal can serve the constructive purpose of provoking some mature and constructive reflection – some evangelical ijtihad, to borrow a theme from Irshad Manji.

I do not in any way want to vilify Rep. Tancredo. The fact is, he cares about something worth caring about: how to stop the vicious cycle of terrorism that seems to be escalating each day. Even if his proposal is as dangerous and misguided as I believe it is, the candidate is to be commended for seeking a solution to this very real danger. I hope that more and more of us will become motivated – and resourced by our faith – not simply to complain about violent solutions to the problem of violence, but instead to make better proposals, because this one, I believe, is a recipe for disaster. To continue living by the sword, according to a reputable authority, is not a sustainable long-term strategy for living at all.

Brian McLaren is board chair for Sojourners/Call to Renewal. His new book, Everything Must Change: Jesus, Global Crises, and a Revolution of Hope, will be released October 2 and explores these issues in more depth and detail.