Many years ago, when I was studying at Drisha, a women’s yeshiva in New York, I was involved in a traditional women’s tefillah (prayer) group. During our services, women would chant from the Torah, and there was some controversy over whether we were halachically permitted to recite the bracha (blessing) over the Torah reading. I asked the Rabbi at Drisha to advise us in our decision.

“Rabbi,” I asked. “May women make a blessing when publicly reading from the Torah in a women’s tefillah group?” He appeared to consider the question for a moment. “Yes,” he said wryly, “That’s certainly the main problem facing Jews today – people making too many brachot.”

I was reminded of this exchange recently, when I came across two separate pieces in the NY Times this week reporting on the dire consequences of too much, or the wrong kind, of parental praise. The first piece, “Too Much Praise is No Good for Toddlers” in the Motherlode blog, cautions parents against praising children’s performance. According to blogger Jenny Anderson, performance-based praise is “like crack for kids: Once they get, they need it, and they want more. And the real world doesn’t praise them for getting dressed in the morning.” The second piece, Boomer Parent’s Lament, suggests that recent college graduates are particularly ill-equipped to handle the sour economy because of the amount of praise their parents heaped on their accomplishments throughout their childhood. In the midst of this crisis, “you can’t remind them how special they are,” Timothy Egan writes, “because that was part of the problem.” (emphasis mine.)

“Yes,”I thought, just as wryly.”That’s certainly the main problem facing families today. Parents saying too many nice things to their children.”

I agree that children love and seek out praise (though as much as an addict craves crack? That I’m not so sure about.) It’s something I see constantly, but especially at the Shabbat table when, after the traditional blessing, my husband and I share something specific from the past week that we are especially proud of. Yes, the girls beam with pride after our recognition, and yes, they remind us with urgency when we forget, but no, I don’t believe this means they will be unable to succeed in the absence of a personal cheerleader. Rather, I think we’re giving them what a former mentor once called “money in the bank.” When no one’s around to tell them what a good job they just did, or how talented they are, they’ll be able to make a withdrawal from the many deposits my husband and I made to their positive sense of self.

I agree that children love and seek out praise (though as much as an addict craves crack? That I’m not so sure about.) It’s something I see constantly, but especially at the Shabbat table when, after the traditional blessing, my husband and I share something specific from the past week that we are especially proud of. Yes, the girls beam with pride after our recognition, and yes, they remind us with urgency when we forget, but no, I don’t believe this means they will be unable to succeed in the absence of a personal cheerleader. Rather, I think we’re giving them what a former mentor once called “money in the bank.” When no one’s around to tell them what a good job they just did, or how talented they are, they’ll be able to make a withdrawal from the many deposits my husband and I made to their positive sense of self.

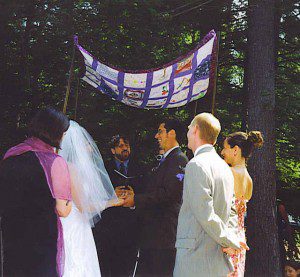

At the same time, I believe the model of the traditional shabbat blessing provides an antidote to some of the potential risks posited by the two articles. First of all, by invoking God, we remind our children that there is a ever-present source of unconditional love and support. Second of all, by wishing that our boys be like Efraim and Menashe, and our girls like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, we remind them that we expect them to constantly grow – that they have many wonderful qualities, but also have many more to develop. There’s always room to grow. Growth that’s not about what grade you get, or what trophy you bring home, but your middot, your values and how you walk through the world.

This is why I was surprised to come across an modern, alternative parental shabbat blessing in Anita Diamant’s book How to Raise a Jewish Child. The new version, by Marcia Falk, urges children to “be who you are”, rather than invoking our ancestors. Perhaps I misunderstand Falk’s intent, but to me, this version smacks of some serious hubris. Are there any children who are so perfect and so complete that they need not emulate our ancestors in any way? While I’m sure this new blessing is no more dangerous than the “wrong” kind of praise, I question the motivation for this new, improved version when the traditional fits the bill.

In the end, I do agree that constantly fawning over your child’s every little achievement might not be in his/her best interest. Does that mean I regret applauding wildly the first time Ella wrote her name, or practically throwing a party when Zoe made her first poop in the potty? Absolutely not. I’m crazy about my children, and I want them to know it. I’m not willing to hesitate before complimenting them in order to consider Anderson’s advice (tone: encouraging, but not celebratory; words: carefully selected to concentrate on effort, not output.) If the worst thing my child has to say about me on the therapist’s couch is “she praised me too much”, well then, mea culpa.

Shavua Tov.