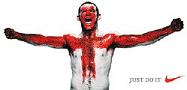

No need to wake early and drink warm beer to enjoy the World-Cup-time flap over English soccer star Wayne Rooney’s new billboard for Nike, left, which has scandalized churchmen in the Sceptred Isle because it recalls the Crucifixion. “‘The trivialization of Christ’s suffering is highly offensive to Christians and to God,” says one cleric. “This will cause real hurt to people.”

No need to wake early and drink warm beer to enjoy the World-Cup-time flap over English soccer star Wayne Rooney’s new billboard for Nike, left, which has scandalized churchmen in the Sceptred Isle because it recalls the Crucifixion. “‘The trivialization of Christ’s suffering is highly offensive to Christians and to God,” says one cleric. “This will cause real hurt to people.”

The second part of this statement may turn out to be prophetic. Rooney’s war cry might encourage fan violence, which European authorities finally seem to have quelled, which would be an obvious shame. But the red cross shouldn’t offend Christians any more than the Swedes’ yellow one or the Danes’ blue one, which their fans commonly slather on their bodies. The swaths on Rooney’s torso represent England’s traditional banner, the flag of St. George. (The Union Jack is the standard of the United Kingdoms of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, all of which have their own teams.) It’s the banner under which King Richard Lionheart’s men marched off to the Crusades–another reason, a disconcerted Labor MPs says, the image is too touchy for good taste, considering the war in Iraq.

If the red cross summons delicate associations, however, it’s a coincidence of England’s past (often a violent one) as an unambiguously Christian nation. Certainly no one is proposing the cross be removed from all national displays.

The Rooney ruffle comes on the heels of a smaller flap on these shores about the place advertising occupies in our media. During last week’s U.S. Open golf championship, Nike ran a commercial that memorialized Tiger Wood’s father, who died this spring. Critics said the spot capitalized on Earl Wood’s death. But the Woods family, which gave Nike all the footage, clearly viewed it as a tribute. The ad was Tiger’s way of communicating his loving grief to his fans.

Rooney’s image is haunting, even hard to look at, and its power unquestionably comes in part from its resonance with Christ crucified–not the suffering of Christ itself, of course, but hundreds of thousands of depictions in Western art. Nike has a right to that history, of course, as much as anyone who is trying to capture complex feelings to communicate about what we see or believe. In other words, to create art.