Any Tolkien fan can tell you that J.R.R. Tolkien, a faithful Catholic, was pals with pop theologian C.S. Lewis, and that he laced his Lord of the Rings trilogy with Christian theology. What’s not always obvious, however, is how. What’s a hobbit got to do with the Messiah?

Any Tolkien fan can tell you that J.R.R. Tolkien, a faithful Catholic, was pals with pop theologian C.S. Lewis, and that he laced his Lord of the Rings trilogy with Christian theology. What’s not always obvious, however, is how. What’s a hobbit got to do with the Messiah?

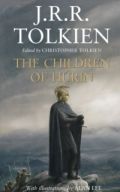

The “new” Tolkien book, “The Children of Hurin” provides few clues to the casual reader. One of Tolkien’s “Lost Tales”—early, unpublished Middle Earth stories written before “The Hobbit”—the new book was edited from manuscripts by Tolkien’s son Christopher. You can see the master of Middle Earth’s style developing: it’s Tolkien, only more so: the battle scenes thrum so mythically that they sound at times like a translation of “The Baghavad Gita.” The good guys are impliably, humorlessly principled. The plot is downright Greek: Our hero, a man named Turin, makes every tragic mistake available to a mythic mortal, including a few Sophocles didn’t think of. Then he dies.

After all, he’s only human. “The Children of Hurin” confirms that Tolkien’s great spiritual subject is incarnation. In this book, as in his famous trilogy, taking physical form is a grim weight that leaves us susceptible to the workings of evil. And if the battle between good and evil takes place in this physical realm, those fully incarnated beings called humans are the main battleground.

Round One of that battle, recounted in “The Children of Hurin,” goes to evil, and neither salvation nor the cavalry is anywhere to be seen by the end. In his forward, Christopher suggests that Turin’s story is based in part on his father’s childhood at the end of the 19th century. If so, it’s no wonder the adult Tolkien would become one of the most prodigious fantasists of the 20th. Any fabricated world would be better than the one that inspired the miseries endured by poor Turin.