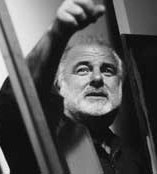

Unless you’re a true Hollywood insider (or a N.Y. Times magazine reader), you’ve never heard of Milton Katselas. But this veteran acting coach is responsible for shaping countless souls into true actors. Head of an acting school called the Beverly Hills Playhouse, Katzelas’s students and admirers include Giovanni Ribisi, Tony Danza, Patrick Swayze, and Michelle Pfeiffer. Katzelas is also a Scientologist, a fact that would be unremarkable if his religion was, say, Judaism or Christianity, but this being Hollywood and Scientology, his faith is cause for raised eyebrows.

Unless you’re a true Hollywood insider (or a N.Y. Times magazine reader), you’ve never heard of Milton Katselas. But this veteran acting coach is responsible for shaping countless souls into true actors. Head of an acting school called the Beverly Hills Playhouse, Katzelas’s students and admirers include Giovanni Ribisi, Tony Danza, Patrick Swayze, and Michelle Pfeiffer. Katzelas is also a Scientologist, a fact that would be unremarkable if his religion was, say, Judaism or Christianity, but this being Hollywood and Scientology, his faith is cause for raised eyebrows.

Like any sincered and dedicated religious person, Katzelas’s doesn’t–can’t–leave his faith at home or at the local Scientology center. It imbues who he is and how he does his business. But that doesn’t mean he’s overly proselytizing in the classroom or quoting “Dianetics” in every other sentence. The portrait that emerges from last week’s Times Magazine profile by Mark Oppenheimer–one of the finest religion reporters out there these days (and an acquaintance of mine from college)–is much more complicated.

Nearly all of the Beverly Hills Playhouse’s employees have some connection to Scientology, Katzelas has a picture of L. Ron Hubbard on his desk, and has been known to quote in lectures a certain “cat that I study”–that cat being Hubbard himself. Perhaps more significantly, his method of teaching and his approach to acting have direct correlations to Scientology’s teachings about As Oppenheimer comments, “What if the playhouse was a serious conservatory, and Katselas a master teacher, not in spite of Scientology but because of it?” For example:

Katselas is adamant that he doesn’t care what his students have been through. Digging into the past might work for some students, and as an avowed pragmatist Katselas tells actors to use whatever works. But he mostly gives actors bits of physical direction rather than asking probing questions about their motivation. In one scene, he had two lovers touch their foreheads together, injecting a note of true intimacy into what had been pure farce; in another, he told an angry junkie to clench his hair in his fists and yank, and all of a sudden the actor found the rage that had been missing from his performance.

“The purpose of the acting art is not to bring about therapy,” Katselas told me later. “One taps their own experience of love or violence and tries to pull from it whatever is possible in terms of an association or understanding, but there is also the imagination and the character and the writing. The personal thing is always very strong and can be created, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you go into the traumas of your life in order to get it.”

Is this teaching Scientology? Not at all. But it happens to be quite consonant with Scientology, which is famous for its opposition to psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Though a few people have left Katselas’s school because of the Scientology influence, more have shrugged it off. If his approach helps them become better actors and boosts their careers, they say, what’s the difference what influences or underlies Katselas’s teaching?

Oppenheimer clearly has his problems with Katselas, his approach, and his unmitigated belief in his own genius. But ultimately, Oppenheimer’s article brings up the same questions as debates about religion in politics or in public schools: How much is too much? Where’s the line between practice and proselytizing, between faith molding who you are and faith being unduly imposed on others?