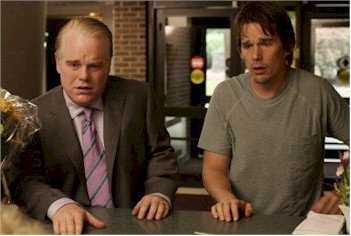

The title of Sidney Lumet’s latest is lifted from the old Irish saying “may you be in heaven thirty minutes before the devil knows you’re dead,” the entirety of which is typed across the screen as a disguised Ethan Hawke watches a bullet-riddled robber fly through the doors of his parents’ jewelry store, set smack in the middle of suburban sprawl. In the film, which Lumet directed from a script by playwright Kelly Masterson, the half hour in heaven probably belongs to Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a broker who coerces his dim, sensitive younger brother Hank (Hawke) into robbing the store run by ‘mom and pop’ (Rosemary Harris and Albert Finney), then blissfully sits back, snorting coke in his office, while the robbery goes horribly awry.

The title of Sidney Lumet’s latest is lifted from the old Irish saying “may you be in heaven thirty minutes before the devil knows you’re dead,” the entirety of which is typed across the screen as a disguised Ethan Hawke watches a bullet-riddled robber fly through the doors of his parents’ jewelry store, set smack in the middle of suburban sprawl. In the film, which Lumet directed from a script by playwright Kelly Masterson, the half hour in heaven probably belongs to Andy (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a broker who coerces his dim, sensitive younger brother Hank (Hawke) into robbing the store run by ‘mom and pop’ (Rosemary Harris and Albert Finney), then blissfully sits back, snorting coke in his office, while the robbery goes horribly awry.

Think Cain and Abel transplanted to Westchester or “King Lear” with a whining male Cordelia and a grudge-harboring older son. That, in a sense, is “Devil,” which complicates already strained familial relations with an affair between Andy’s wife Gina (Marisa Tomei) and Hank, and a brother-brother-father showdown that cements the third act in a tragic twist.

“I’ve seen family members kill each other, but this is a real Greek act,” Seymour Hoffman said in a recent interview with me, at the Regency Hotel in New York City, where, along with Hawke and Tomei, he was promoting the film. “There was something about (the script) that echoes way back into our history of theater.”

At the the Regency, a handful of journalists were seated around a table, comparing “Devil” to classic theater. And “The Anderson Tapes.” And “Dog Day Afternoon.” But when Lumet, who at 83 has the ability to shoot a sex scene frankly and complexly (Hoffman and Tomei miserable and nude is one of the most effective opening sequences, sexual or not, I’ve seen this year) showed up, patting Hawke on the shoulder and sitting purposefully down in a fold-out chair, he insisted that conjuring the Greeks – or hearkening back to his critically acclaimed earlier work – wasn’t his intention.

“I thought of it as a good solid melodrama. In other words, a hell of a story,” the director said. “But when people come to their own conclusions, it’s a wonderful feeling because it means you’ve done something resonating that goes past what you were intending. I never thought of it in terms of Greek tragedy. So many reviews are comparing it to “Dog Day Afternoon.” I don’t see that at all, but I’m delighted that people get those echoes, because it means it’s registering with them on a personal level.”

Lumet cast Seymour Hoffman because “He’s such a good actor, he could have played Marisa’s role.” He handed Tomei a detailed biography of the somewhat ambiguous Gina and, according to the actress, “gave her more credit than he gave the guys. It showed me right away what he was looking for, which was a lot more vulnerability than I would have thought right away.” When asked about casting Hawke, Lumet was impressed with his ability to “play a weak character, but there’s nothing weak about what he does.”

That’s precisely why “Devil,” which jumps back and forth in time, works on levels both entertaining and thought-provoking. Shallow characters have complicated motives, complicated characters have shallow motives, and even the most heinous actions are somewhat relatable. “The reason he does the robbery is because he’s so desperate for his brother’s approval,” said Hawke. “But he’s so desperate that he hates his brother. That’s how a lot of weak people work. They cut at other people’s ankles by sleeping with their wife or screwing up a robbery.”

“Do you think he has morals?” I asked.

“In a way he’s worse than his brother because he does have morals. He has a conscience and his conscience haunts him. Eventually, after like ninety million people get killed, he puts his foot down. Which is more than anyone else does, but it’s not enough. People relate to him is because we all relate to having a conscience and not doing anything about it. That’s not terribly unfamiliar to anybody.”

–written by Jenny Halper