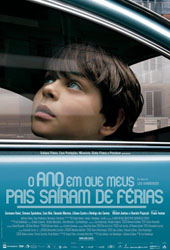

You may not have heard about “The Year My Parents Went on Vacation” yet, but you likely will. The film, which is billed as being in Portuguese, Yiddish and Hebrew (a bit of a misnomer since the Hebrew is all liturgical and goes untranslated as background flavor) with English subtitles, takes the audience back to 1970, a year that apparently was fraught with civil unrest, student rebellions and emergent communism for Brazil. Also emerging was the national pastime, football (that’s soccer to you Americans), since Brazil was hoping to win the World Cup that year, and that sport serves as the buoy of hope for a young boy, left alone at his grandfather’s door-step by his parents, who claim to be departing for a “vacation” — it may not be clear why they’re leaving to the audience or to the boy, but it is clear that vacation is not at all what they’re doing.

You may not have heard about “The Year My Parents Went on Vacation” yet, but you likely will. The film, which is billed as being in Portuguese, Yiddish and Hebrew (a bit of a misnomer since the Hebrew is all liturgical and goes untranslated as background flavor) with English subtitles, takes the audience back to 1970, a year that apparently was fraught with civil unrest, student rebellions and emergent communism for Brazil. Also emerging was the national pastime, football (that’s soccer to you Americans), since Brazil was hoping to win the World Cup that year, and that sport serves as the buoy of hope for a young boy, left alone at his grandfather’s door-step by his parents, who claim to be departing for a “vacation” — it may not be clear why they’re leaving to the audience or to the boy, but it is clear that vacation is not at all what they’re doing.

There are many things that this film made me notice: the Latin American obsession with football, a dawning awareness that communism wasn’t over by 1970, and that no scene in which a character whips out a straight-edged razor ever ends well. But there were two themes that I found particularly resonant. The story is told through the eyes of Mauro, a young, abandoned boy who has been plunged into a foreign environment–still within the borders of his own land, but not within the borders of his own experience. He learns quickly that there are foreign worlds–like the Jewish community in which everyone speaks Yiddish, and the world of puberty and adolescence that hits him with a crush on a local waitress and his interactions with the young girl down the hall. As Mauro finds himself in a Jewish community for the first time in his life, he encounters objects and people as strange to him as if he were a foreigner in a strange land, which in some ways, he is.

The film also makes a statement about sports that’s undeniable: that a national pasttime can unite members of different communities in a national endeavor: it’s post-denominational nationalism at its purest, reaching beyond age, politics or religion to bring people together in common tension and triumph.

There’s literal word on the street that the film is being prepped as Brazil’s entry to the Best Foreign Film category at the 2007 Oscars. (I was walking on the street with my friend, who stopped to talk to a random dogwalker who happened to be Brazilian, had heard of the film, and told us this was the case.) I’m not surprised: it’s a tense story of a fish out of water, hope despite hopeless circumstances, love and peace amid unrest and violence, and throughout it paints a multiply-complected Brazilian society that’s as stratified in “real life” as it is unified during the World Cup. The abandonment theme is difficult, but is pointed to by the name that the Jewish community assigns to Mauro, the boy who figuratively floated down the river to them…Moshe, they call him.