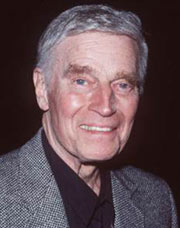

If many Americans actually pull up Charlton Heston’s face-wigged visage when they think of Moses, it’s worth noting that Time magazine considered Heston “ludicrously miscast” as the biblical patriach in Cecil B. DeMille’s epic “Ten Commandments.” The hammy, melodramatic style of Hollywood’s big-budget midcentury heyday obscures the fact that Heston, who starred in some of the most overblown productions of the time, was a powerful enough actor to anchor these operatically-scaled monstrosities–and imprint his depictions of mountaintop characters like Moses on our hearts and retinas.

If many Americans actually pull up Charlton Heston’s face-wigged visage when they think of Moses, it’s worth noting that Time magazine considered Heston “ludicrously miscast” as the biblical patriach in Cecil B. DeMille’s epic “Ten Commandments.” The hammy, melodramatic style of Hollywood’s big-budget midcentury heyday obscures the fact that Heston, who starred in some of the most overblown productions of the time, was a powerful enough actor to anchor these operatically-scaled monstrosities–and imprint his depictions of mountaintop characters like Moses on our hearts and retinas.

Heston never shied from religion. Besides Moses, he played Ben-Hur and the Christian warrior El Cid. Given the superiority of the Oscar-winning 1965 movie version of “A Man for All Seasons” starring Paul Scofield, we suspect Heston’s 1988 remake, with him in the title role, was made out of devotion to the story of Thomas More’s implacable faith.

But it’s a mistake to think Heston was always the champion of iconic faith. In the mid-’70s he played a thoroughly corrupt Cardinal Richelieu in a randy version of “The Three Musketeers,” and earlier, in 1968’s “Will Penny,” he plays a rancher at odds with a firebrand preacher, in a sort of “There Will Be Blood” of its time. Heston valued his morally ambiguous work, seen in films like “A Touch of Evil,” directed by Orson Welles, and was always ready to lampoon his bloated Mosaic image in turns in “Wayne’s World” and “Friends.”

Though he was patently conservative politically–he was to Hollywood what his friend Ronald Reagan became to politics–Heston was more talented and more complex than his place in modern-day comedy monologues may reflect. It’s impossible to tell the history of Hollywood, and maybe of 20th century international politics, without movies like “Soylent Green” and “Planet of the Apes.”

Certainly Heston deserves to be remembered better than the waning, befuddled star caught by Michael Moore in “Bowling for Columbine,” defending his appearance at an NRA rally in Flint, Mich., after the gun death of a young woman there. Moore’s film style depends on stick-figure simplicity as much as Heston’s depended on greasepaint and swirling clouds of smoke. Their collision flattered neither man.

Rather, Heston should be remembered as a guy who could play multidimensional characters on any scale, and hold together some of Hollywood’s craziest notions. Imagine your favorite Hoffman–Dustin or Philip Seymour–uttering a line like “Take your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape” and living to tell the tale.