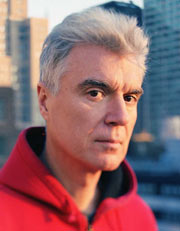

I’m betraying myself as incorrigibly uncool by mentioning this, but David Byrne has a couple of new albums out. “Everything That Happens Will Happen Today,” made with Brian Eno, slunk onto the web last August with the lack of fanfare that denotes hipster disdain for the record business nowadays. The other is, ” Hymnal,” a soundtrack of Bryne instrumentals for “Big Love,” the HBO show about the fictitious, upscale, fundamentalist polygamist Mormon family. Both recordings have given critics to see a spiritual moment in Byrne’s work, and Bryne has encouraged that kind of talk.

I’m betraying myself as incorrigibly uncool by mentioning this, but David Byrne has a couple of new albums out. “Everything That Happens Will Happen Today,” made with Brian Eno, slunk onto the web last August with the lack of fanfare that denotes hipster disdain for the record business nowadays. The other is, ” Hymnal,” a soundtrack of Bryne instrumentals for “Big Love,” the HBO show about the fictitious, upscale, fundamentalist polygamist Mormon family. Both recordings have given critics to see a spiritual moment in Byrne’s work, and Bryne has encouraged that kind of talk.

Once upon a time it was dangerous to take anything Byrne said at face value. Talking Heads of the 1980s reveled in the drama of no drama. Psychokillers fixated on the most ordinary things (“I hate when people aren’t polite”) and social critics spoke out against not high crimes and misdemeanors but baseball diamonds, large automobiles and other signifiers of unremarkable American life. Besieged by the normal, Byrne’s persona was hysterically calm. When he sang, “it shows what a little faith can do,” his achievement was getting through his day. In a landscape where the paranoid has “learned not to stand by the window,” nothing is safe, and nothing means what we think it does.

Toward the end of the T-Heads run, though, optimism began to bleed into their albums. On 1983’s “Speaking in Tongues” Byrne had already begun to express a fragile sense of hope. “Home,” he sang, “I want to go home, but I guess I’m already there.” But the spiritual uplift was unmistakable by 1985, when the album “Little Creatures,” with its cover art by folk artist and Baptist minister Howard Finster and life affirming lyrics about bouncing babies, boasted titles like “Creatures of Love” and “Perfect World.”

“Everything That Happens Will Happen Today” is a continuation in this positive vein. Byrne and Eno both cite gospel influences in the music and biblical allusion, references to being reborn and even saints trip through the new album. Byrne explains that the challenge of this album was to write “simple, heartfelt tunes,” and is satisfied with the “uplifting, hopeful, and positive” results. “Life is long if you give it away,” he says in a Christ-like philosophical inversion.

Yet the longtime Byrne fan yearns for a little of the old irony: does the plain-spoken affirmation not bear a tiny crimp of the irony as the plain-spoken paranoia that preceded it did? “Hymnal,” released last August as well, but resurgent since the debut of the HBO show’s new season, is full of billowy horns and strings that sound like American church music. The best moments of the album seem to draw on Leonard Cohen’s reverent anthems, but Byrne’s is reverence without doubt, without risk. “Big Love” itself is a scalding criticism of the intricate self-justifications of living by religious law, more a Hollywood parody of evangelicals than of any form of Mormon. But one listens in vain for a barked out note of Byrne’s old parodic style to accompany it.

Nor will you find it on “Everything.” The music is beautiful at times, the lyrics in love with the world, but the spirituality is not connected sinew-to-bone to that world, and though Byrne dedicates himself to avoiding cliché, he time and again falls back on it. “The river’s moving on from here to sing its crazy symphony,” he sings on the “The River,” a song about Hurricane Katrina according to Byrne but which seems really to be about being a musician, which, through allusion, chord structure and a kind of wan hopefulness, is the sense in which his music is spiritual. He had more to tell us about the world when his religion was existential despair.