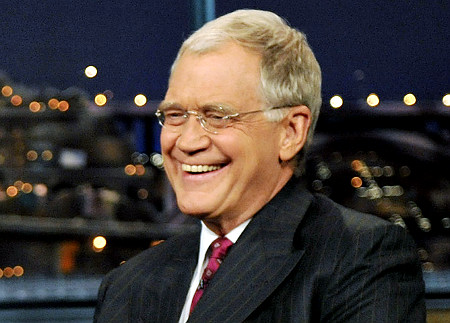

David Letterman performed a ten-minute comedy routine last evening about how he’d been blackmailed. The punchline was that he had indeed had sex with female employees, the scuttlebutt that his blackmailer, reportedly a producer for the CBS show “48 Hours,” had threatened to reveal. “The answer is yes, I had sex with women who worked for me on this show,” he declared. At that, the audience burst out in applause.

David Letterman performed a ten-minute comedy routine last evening about how he’d been blackmailed. The punchline was that he had indeed had sex with female employees, the scuttlebutt that his blackmailer, reportedly a producer for the CBS show “48 Hours,” had threatened to reveal. “The answer is yes, I had sex with women who worked for me on this show,” he declared. At that, the audience burst out in applause.

It was a strange moment, one of those that you couldn’t sit through if it weren’t on television, and maybe only on Letterman. He whipped out a Letterman-esque word, “hinky,” to express the creepy feeling of being spied on, and and owned up to a Midwestern, Lutheran sense of guilt. (Okay, Garrison Keillor is the other guy who could have pulled it off.) It was strange enough to watch Dave get laughs with a script wrung dry, no doubt, by lawyers, p.r. types, and networks execs. But the applause was the oddest feature. What, precisely, was the audience applauding?

Obviously, they were supporting a guy they like and admire. But Letterman also made an implicit statement about the truth. He didn’t defend his right to have sex with his employees–he said he “hoped to keep my job,” and he repeatedly voiced concern about the women’s reputations. But in busting the blackmailer, now under arrest for attempted grand larceny, he forwarded the idea that sex is most embarrassing to oneself and damaging to others when you lie about it, try to hush it up.

It’s not Dave’s idea. Nathaniel Hawthorne floated it in 1850, when he published his novel “The Scarlet Letter.” The most conservative Christian politicians and ministers have learned the lesson and immediately submit to their own personal truth commissions as soon as scandal breaks. Yes, these men are usually gambling that an honest admission would save them face and, in the long run, power and money, reckoning that Americans will be more forgiving if you treat us like the grown-ups. And we are. The audience was in a sense clapping for itself.