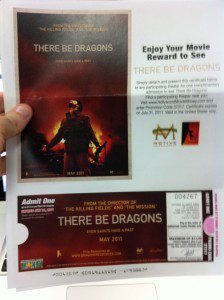

NOTE: We’re currently giving away 10 pairs of tickets to see There Be Dragons. Go here for details.

Director Roland Joffé has never shied away from overtly religious themes in his films. “The Mission,” his Oscar-winning 1986 film about a Jesuit mission in South America, embraced themes of faith, sacrifice, and redemption. It is, without a doubt, one of the most beautiful and spiritually challenging films I have ever seen.

Joffé’s latest film returns to those themes of belief and forgiveness. Set during the Spanish Civil War, There Be Dragons (opening Friday, May 5th) deals with Josemaria Escriva, the controversial founder of the Catholic order Opus Dei who was later canonized by the church. I had a chance to talk with Joffé about the film, its controversial subject, and why ‘religion is life.’

EVAN DERRICK: When dealing with religion, directors tend to take one of two routes – to vilify it or place it on a pedestal. You seem to take the middle road, that religion and those who practice it can do great evil but also inspire incredible good. Is that a conscious effort on your part or just instinct?

ROLAND JOFFÉ: I think that religion plays an important part of many people’s lives. The majority of There Be Dragons is set during the Spanish Civil War, a time period that was very difficult for the Spanish people. It gave me the opportunity to ask the question: is God to be found there, in the midst of war? And if He is: How?

The church is made of human beings, so, it’s going to have human failing. And, I think that is extraordinarily important not to ignore. The church is extraordinarily beautiful and I love great cathedrals; I love the vestments; I love all those things.

I think Christ infuses every moment in the movie. I don’t mean that in a grandiosely religious way. I mean He is there, because this is a movie about suffering. And Christ is in suffering. That seems to me to be something that Christ really understood. And this is something that’s profoundly understood in Christianity; and, I think, is a remarkable message. Whatever my personal beliefs about religion may be and my personal agnosticisms, I can’t refute the extraordinary creative and redemptive power of that.

ED: What is your relationship to traditional religious institutions? Is it as complicated as some of your films imply it is?

RJ: My career has been rather eccentric; I don’t think of myself as a “director”. I think of myself rather as a a human being intrigued about this extraordinary experience that I’m enjoying so much, which is called ‘life’, and what it might mean to me and what it might mean to other people.

The questions contained in religion are unavoidable; because religion in a sense is the incarnation of questions. One of the things I learned, at a very early age, as I went down to different cultures was that we all have the same questions. I haven’t been to any culture – and I have been to quite a few – where the questions are not profoundly: What do I mean? Why do I die? Why does love not make everything right? What’s hate?

The truth it seems to me, about any religion that’s worthwhile, is that it connects up to something essentially fundamental, about what it is to be a human being. And, then, it allows you to either explore that in a structured way or in a less structured way. So, I don’t think that any human being – alive and allowing themselves to live – can avoid the questions that, we say, are posed by religion.

In a way then, life is religion.

ED: What is it about period epics that fascinate you so much? Do period settings lend your stories a certain quality you could not otherwise find in a modern setting?

RJ: The job of the movie world is not to say: ‘This is a perfect historical reconstruction’. It’s to say: ‘This is what it felt like’. I remember, in The Killing Fields, hearing an interview that Jon Swain gave, where somebody said: ‘When you were captured, what happened?’ So, he gave a description, and the journalist said: ‘But, that’s not how the film describes it!’ And Jon Swain said: ‘Ah, it’s not. It’s true, in a sense, that what the film showed is not, exactly, what happened. But, I’ll tell you this: more importantly, it’s what it felt like.’ And, that’s the job of a movie: to connect a feeling to an event. So, obviously, what I have to do – in the way we assemble images and make everything work – is to get inside and recreate that feeling. I felt my job was to look beneath the ideological conflicts to find out what human beings were actually doing and how this expressed itself.

There Be Dragons is set in a particular period of time which, I happen to think, was important because it was, so much, the apotheosis of ideology and its expression – and how it was forming the way human beings behaved. I had to find characters that were always leading people back to the central importance of human acts, and what those acts meant in an emotional way. The burden of that; the responsibility we have; the way in which suffering is passed, from one person to another; the burden of other people’s pain: that all those things are the warp and woof of life, and should not be avoided. The Spanish Civil War provided such a backdrop.

ED: There has been a lot of controversy over Opus Dei, mainly due to Dan Brown’s portrayal of it. In what light do you hope “There Be Dragons” will cast the organization?

I think there’s a misunderstanding about how Opus Dei works. And, as the film shows, Opus Dei is about individuals. So, in a sense, there is no ‘Opus Dei policy’. Opus Dei really can’t be behind anything. I mean: three or four, or even twenty or thirty Opus Dei members may agree on some elements of something – though, from what I’ve met of them, they’re never going to agree on all of them, anyway; which, I think, is extraordinarily healthy!

I think I was pretty open-minded, really, about what the organization was and what it might be.

ED: St. Josemaría Escrivá is a very polarizing figure in Catholicism. Some venerate him and his teachings calling all to holiness, others revile him as a mean-spirited man who allegedly sympathized with Hitler. How will There Be Dragons tackle these warring opinions? What portrait of Escrivá do you hope will emerge from the film?

RJ: I spent a lot of time thinking about how one makes a story about a Saint, and I realized that the danger would be to abstract the Saint from life by focusing the film on the Saint’s life. That seemed to be a betrayal of most of the Saints I had read about – most of whom appeared as real people who dedicated their lives to other people. The question for me was, ‘What kind of world did Josémaría find himself in?’ And, ‘What was going on, in that world, which, in some senses, would become a setting for Josémaría to become a saint?’

I wanted to use a number of different stories from Josémaría’s life in homage to the idea of what a Saint is. I’m not a priest. So, everything I have to say about being a priest, I have to pass on, at second hand, including what I read about Josémaría and the videos I saw of him. As I would do with any actor – whether it was a policeman, a soldier or a pilot – I would find somebody who was that thing and get the actor to talk to them, so they’d get it from the lion’s mouth. What I was trying to do, consistently, was to link things; but, to make the links rather curious – so that there were links between Josémaría and what he was saying and the other characters in the film.

ED: With There Be Dragons are you interested in inspiring people in their faith? Challenging them? Forcing them to examine their beliefs more deeply? Or just presenting a good story, well told?

I think that as I looked at Josémaría’s life, it posed questions to me. I thought, could I encapsulate those in a story. I hope, like good stories, it is not wagging a finger, but rather a plunging into a life-moment, where you feel. And, for me, the absolute key is: in that moment, will there be feeling? Because, if there’s no feeling, then it’s just an intellectual exercise and there’s no connection. If we are feeling pity and fear that forgiveness will not be there, then we’ve connected.

What struck me about Escrivá was a remark he made about ‘God being found in the everyday’, and what that actually meant. In a way, one can take it as meaning: well, God is found in the bakery and He is found in the haberdasher’s. But, that’s not what he means, I don’t think. I think he means the everyday. And the everyday, when you really think about it, is not just the baker making his bread: it’s the baker wondering whether he should divorce his wife when he’s making his bread. And, I realized that what he was saying was something profoundly deep, in very simple words.

The balance of values, then, becomes very important. In the film, you’re not selling the audience out saying, ‘See! You’ve watched a movie about a Saint! Look how important that is and look what lessons are here!’ What you’re saying to the audience is: ‘Examine the tapestry. Threaded through this tapestry is the story of a man who has, now, been accepted and welcomed as a Saint.’ But, if you were to extract that from the tapestry: what would you have? You would only have a thread. Therefore, the tapestry is extraordinarily important.

There Be Dragons opens nationwide on Friday, May 5th.

[bcvideo vid=’905791941001′ pid=’96582452001′ height=’410′ width=’480′]