Easily the best media moment for the Mormon Church in the past year is “New York Doll,” a documentary about the last days of rock bassist Arthur “Killer” Kane. The movie, released theatrically last fall and on DVD April 6th, shows that it’s possible to be a Latter-day Saint while maintaining legendary cult status, reuniting with your old band, and finding redemption.

Easily the best media moment for the Mormon Church in the past year is “New York Doll,” a documentary about the last days of rock bassist Arthur “Killer” Kane. The movie, released theatrically last fall and on DVD April 6th, shows that it’s possible to be a Latter-day Saint while maintaining legendary cult status, reuniting with your old band, and finding redemption.

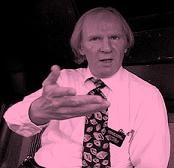

Kane was a founding member of the New York Dolls, a group that was for the punk/New Wave revolution what, say, Buddy Holly was to rock ‘n roll’s first generation: a bolt-from-the-blue talent that changed everything, then vanished. The film finds Kane living in Los Angeles in 2004, 30 years after the band dissolved, thanks to drug-related deaths, heroine and Kane’s own alcoholism. After hitting bottom—he jumped out a window after seeing former bandmate David Johanson in the movie “Scrooged”—Kane discovered Mormonism, which he credits with saving his life. We meet Killer’s co-workers at the Family History Center at L.A.’s LDS Temple, as well as his former and current bishops and other assorted Mormons—all apparently reasonable, faithful people who accept Kane’s history and support him when the call comes from London for a reunion with the two other remaining living Dolls.

Greg Whitely, the director of “New York Doll” met Kane at church, and the film appealingly recreates his slow-dawning realization that Kane, a gawky, seemingly naïve specimen, is the object of awe and respect among some of rock’s top names. What makes “New York Doll” a serious spiritual film is Kane’s (and his co-religionists’) appreciation for the Dolls’ reunion as a sacred moment. The concert’s critical and musical success pales for Kane next to the chance to restore his relationship with Johanson, whom he’d turned into a symbol of his own failure and lost glamour, and whose attention and love he still seeks out as a supplicant.

Kane’s renewal doesn’t return him to a pure state, but gives him his life back with his scars intact. We see that he sees it, and through the rasping, impish Johanson’s goading about his conversion, Kane exhibits a dignity that his old pal’s stardom can’t tarnish. Kane unexpectedly died less than a month after returning from London, from leukemia, and this film is the perfect epitaph to a life badly lived, but fully realized.