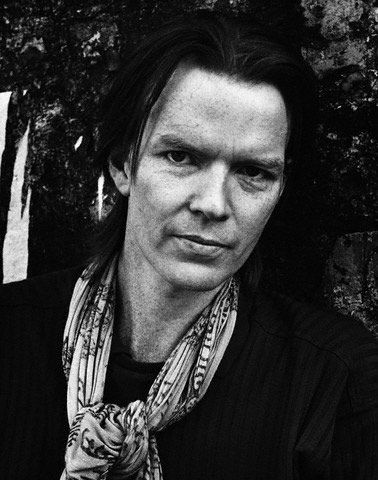

Solitary, spare in his poetry and his person, the writer and musician Jim Carroll, who died last week at age 60, was never easy to take as an artist. His songs were punk rants, his poems drug-scorched versions of Frank O’Hara’s versified journal entries of life among the hip. Carroll’s tone was plaintive, and he drew from his Roman Catholic spiritual heritage a sense that suffering–his own, mostly–was both preordained and the result of a flawed worldview: as he sang in his signature song “Catholic Boy,” “I was a Catholic boy/I was redeemed through pain/Not through joy.”

Solitary, spare in his poetry and his person, the writer and musician Jim Carroll, who died last week at age 60, was never easy to take as an artist. His songs were punk rants, his poems drug-scorched versions of Frank O’Hara’s versified journal entries of life among the hip. Carroll’s tone was plaintive, and he drew from his Roman Catholic spiritual heritage a sense that suffering–his own, mostly–was both preordained and the result of a flawed worldview: as he sang in his signature song “Catholic Boy,” “I was a Catholic boy/I was redeemed through pain/Not through joy.”

Carroll himself, though talkative and friendly by all accounts, was often oblique in public–though more than one observer corrected the feeling of disconnectedness Carroll gave off to allow for Carroll’s heroin habit. As a biography, some of which he put down in his bestselling “The Basketball Diaries,” Carroll can frustrate you too: having won a scholarship to an elite Manhattan high school and going All-City as a basketball player, he chucked his early achievements to pursue a drug-infused career that produced only a small body of written and recorded work. With his Catholic-boy grudge and his Lower East Side upbringing, he conjures up a psychedelic 1960s version of the Dead End Kids.

Other times he recalled another Irish-blooded pessimist, Samuel Beckett: again, from “Catholic Boy,” “I was convicted of theft as I slipped from the womb/They led me straight from my mother to a cell in the Tombs.” That’s life, according to Carroll, and in his loving but unredeeming hit song “People Who Died,” death is a blank, sometimes preceded by a small, heartless twist of irony.

The key to understanding Carroll may be in a remark he made to journalist Frank Rizzo 30 years ago. Repeating his standard line in those days about playing basketball–“It’s not that you just scored two points but that you look good while doing it”–Carroll added, “It’s a chance to transcend yourself.”

Carroll seemed to have spent his life chasing those chances. The immortality poetry offered, the energy-surge of performing rock music, the chemical alienation of drugs, the physical grace of a perfect jumpshot–they might have been Carroll’s breaks from the angst of being human, which he so sorely felt.