Kathrine Switzer helped change the future of women’s sports by becoming the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon. It wasn’t easy—an iconic photograph of the 1967 race shows a man attacking and grabbing at Switzer mid-run, in an attempt to get her off the track, as her coach and then-boyfriend defended her.

Her disqualification? Running while female.

In 1967, the Amateur Athletic Union rules did not allow women to officially participate in long-distance running in any of its sanctioned marathons. But according to Switzer’s memoir, “Marathon Woman,” there came a moment when she knew she was going to run it, anyway.

Switzer’s then-coach, Arnie Briggs, himself a veteran of 15 Boston Marathons, was fond of telling stories of famous Boston Marathon runners. Switzer loved listening to these, but one night, grew tired of hearing about these experiences secondhand, expressing her interest in running the race.

Arnie’s response?

“No woman can run the Boston Marathon.” The distance was too much for “fragile women.”

At her insistence, though, Arnie agreed to take her to Boston if she could first prove her ability to run the distance—26 miles.

She did—in fact, as Switzer’s memoir shows, she outpaced her coach, who promptly passed out after a 31 mile practice run.

When it came time to register for the race, Switzer used her initials—K.V. Switzer. This wasn’t an attempt to sneak past the guidelines, but was simply the way she signed her name—as a journalist, she felt this was more in line with other popular writers of her time like J.D. Salinger and E.E. Cummings.

On the day of the race, Switzer tried to remain unnoticed, but already the murmurs of amazement were brewing in the other runners. One insisted on taking a picture with her—as the only female runner there, she was a wonder.

The gun went on, and finally, Switzer was there, feet pounding the ground in the marathon she had only dreamed of participating in.

But around mile four, something changed. A city bus outfitted for the press pulled up, cameras clicking toward her. She, and the runners around her, began to smile and wave. When her eyes swept back to the race, though, there was a man in an overcoat and felt hat standing in the middle of the road, shaking his finger. He reached for her as she passed, catching her glove and ripping it from her hand as he tried to restrain her.

Moments after, she heard the sound of leather slapping asphalt, and a voice screaming, “Get the hell out of my race and give me those numbers!” When she turned, a huge man, teeth bared, face contorted with rage, was right there, tearing at the bib that held her marathon number.

This man was Jock Semple—the very organizer of the Boston Marathon. And within seconds, he was intercepted by Arnie, and then tackled by Switzer’s boyfriend, Tom Miller.

Cameras captured all of it, making history.

Later in the race, the press truck caught up with her, the journalists aboard hurling accusatory questions. Even her boyfriend, Tom, the man who had tackled Semple, became combative, blaming her for the situation.

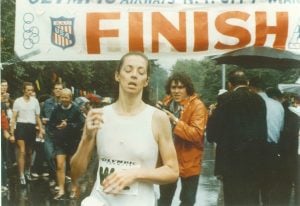

But despite the negativity, Switzer ran finishing the race, proving that women were not too fragile to run long-distance. Her final time was 4 hours and 20 minutes, but she would later be disqualified and expelled from the Amateur Athletic Union for her run.

It made no difference. In the following days, her run was all over the news, and the photo of her being chased by Semple, of her running, and of her finishing the race were all over the news. She would go on, in the following years, to run 40 marathons, and to win the New York City Marathon in 1974.

But for female athletes, her 1967 Boston Marathon run was a huge victory. This was one of the moments that helped take the idea of women in sports into the mainstream, paving the way for later social changes.

Today, Switzer is an acclaimed speaker who addresses cultural and social change, and has made use of her original Boston Marathon runner’s number—261—to form 261 Fearless, a nonprofit running club for women.

Most poignantly, Switzer recently crossed the finish line of the Boston Marathon for the 9th time, on the 50th anniversary of her original, groundbreaking run. She wore her same numbers, which became a rallying cry amongst female runners.

Switzer affirms that things have most certainly changed for the better since that day in 1967 when a man tried to rip the number from her shirt, but in an interview with CNN, she acknowledges that there’s still work to do before women find their equal place in society.

“The race today was a celebration of the past 50 years; the next 50 are going to be even better.”