This lifetime of ours is transient as autumn clouds.

To watch the birth and death of beings

Is like looking at the movements of a dance.

A lifetime is like a flash of lightning in the sky.

Rushing by, like a torrent down a steep mountain.

— Buddha

Over the last two decades I have occasionally taken a week of silence to renew my spirit. A few years ago, I found out that there was a tradition in Thailand where some CEOs of major businesses and politicians would take a week or two of silent retreat as ordained Buddhist monks. This was to remind them to be humble in spirit and anchor themselves in sobriety. When I recently met Joy Sopitpongstorn who is a friend from Thailand, I asked her if it was possible for a “foreigner” to “ordain.” Joy is a long time friend of mine who has attended my courses in India. After making some inquiries, Joy informed me that she had obtained permission for me to come on a “monk’s journey” for two weeks.

So off I went to Thailand on June 26th .

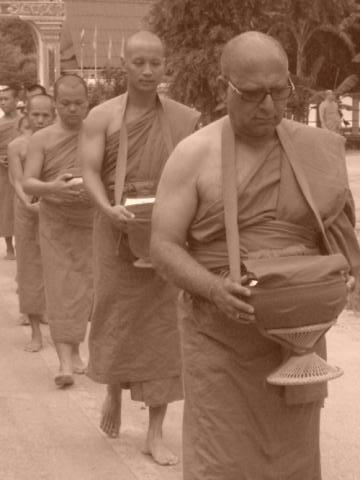

The first part of my journey was to accustom me to “hardship”. For this, I went to the Forest Monastery, Wat Sunandavanaram, under the guidance of a famous but austere abbot of Japanese origin known as the Venerable Arjarn Mitsuo. In this monastery I had to sleep on a wooden floor, wake up at 2:00 a.m. every morning to meditate with the other monks on the impermanence of life and my own physical death. We would do this until 4:30 am in the morning and then practice mindfulness meditation until about 6:30 am; after which we would go for “alms round”. The monks walked barefoot over rough terrain through neighboring villages. Since I was not an ordained monk at this time, I was allowed to wear my sneakers and served as an assistant to the monks. The poor peasants from the villages would line up the streets and make food offerings to the monks. If their bowls filled up, I would empty them into a large bag that I carried so they could be “refilled”.

It was wonderful to see the look of reverence on the faces of the villagers as they offered their alms to the monks who in turn, silently blessed them.

We would return from the alms round around 8:00 am after which, we would have our one and only meal for the day. We all shared the food that was offered to us and ate in silence with full mindful awareness.

The rest of the day was spent in meditation. In the evening we would meet with the Venerable Arjarn Mitsuo who would guide us further into mindful awareness of breath, feelings, emotions, and movement. We would sleep around 10:00 p.m. and then wake up again around 2:00 am for meditation on impermanence and death.

Conditions of this monastery were very basic, with no running water and some mosquitoes to contend with.

After a few days of this hardship, I moved to the Forest Monastery, Chiang Khong, where I was to be officially ordained.

Joy’s brother, Jate, a young man of 36 years decided at the last moment that he would ordain with me. The second monastery under the guidance of the Venerable Abbott Arjarn Ekachai was more comfortable then the previous one in that we had running water.

The ordainment ceremony required us to memorize some of the teachings of Buddha and chant them in Pali. Pali is a Sanskrit derivative language and was indeed the language spoken at the time of the Buddha. Surprisingly, I did not find it difficult to memorize the verses that I was asked to recite for the ordainment.

The ordainment ceremony began at 6:00 a.m. in the morning at the Forest Monastery, Chiang Kong. About 1,000 villagers from 13 neighboring villages showed up to witness it.

After a lot of chanting and instructions by Venerable Arjarn Ekachai and another senior monk on the responsibilities of an ordained monk, including following the five precepts, understanding the Four Noble Truths, and the Eight-fold Path to Enlightenment, we also had to undergo a head shaving ceremony. I did not realize that the shaving would include my eyebrows. But by this time, I had let go of all attachments for the time being and decided to surrender to the whole process. My son Gotham was there to witness and film the ceremony as I and Jate went through the process.

After the head shaving ceremony, the villagers lined up one by one to tie threads around our wrists. This was symbolic and meant that the villagers and monks had embraced us as their family. This part of the ceremony took two hours and Jate and I sat crossed legged on the floor for it.

After the “thread ceremony”, all the villagers were fed food that had been cooked by volunteers. All this took us to about noon, after which Jate and I mounted two elephants as part of a parade to the Buddhist Temple where the ordainment and wearing of the monks robes was to take place. The parade was very festive with drumming, and chanting, and the villagers were all dressed in colorful celebratory outfits.

We dismounted our elephants upon reaching the temple where the actual ordainment ceremony began. This lasted five hours with me and Jate reciting our Buddhist chants to prove that we had done our “homework.”

Finally, we were asked to give up our clothes and exchange them for the monk’s robes. As Jate and I walked out of the temple at about 5:30 p.m. in the evening with our begging bowls and in monk robes, all of the villagers prostrated themselves at our feet with reverence and made offerings and filled up our begging bowls. We were now ordained.

Back in the monastery the Venerable Arjarn Ekachai instructed us on our routine which was to be similar to the one at the previous monastery. Over the next week, we maintained silence and kept the routine as instructed.

My only challenge was walking bare foot through the villages. The country paths were at times rocky and at times full of bristles and thorns but we marched through it despite the pain.

The Venerable Arjarn Ekachai would meet with us in the afternoon and late evening where he would go over our practice of mindfulness.

Because there were no mirrors, we did not know what we looked like to ourselves. The others treated us with great respect and reverence and the villagers were very generous in the giving of alms, which mostly included rice, vegetables, fruit, boiled eggs, and sometimes even a bar of chocolate.

It was amazing to see to see the generosity and love and the reverence in the eyes of the peasants as they offered food to us. We ate once a day as in the previous monastery.

By and by, I started to feel that I was losing my sense of my previous identity. Physically, I was without hair on my scalp or my eyebrows. I walked barefoot. I wore the robe of monks. I practiced mindful awareness day and night, in addition to meditating on impermanence and on my own physical death.

The Venerable Arjarn Ekachai explained that being in this mindful state and shedding our previous identity allowed divine qualities to emerge. – loving kindness, compassion to all beings, happiness at the happiness of others and equanimity. Indeed I felt the truth of all this in my experience.

I realized that holding on to anything is really like holding on to your breath. You begin to feel suffocation. It was freeing to let go.

Before we went to the closing ceremony, we took our hair and packed it in palm leaves and went to the Mekong River, which runs between Thailand and Laos. We boarded a boat and went toward a shrine along the river banks where we offered our hair to the river and it floated away. This was symbolic of letting go of our habitual certainties and attachments and creating the space for new and better and more spiritual things in our lives. The hair, which is part of our body and came from the elements, was returned to the elements.

After a full week, Jate and I returned to Bangkok once again wearing our regular clothes. But, when I looked into the mirror, I could not recognize myself and burst out laughing.

What did I learn?

1. When we let go of our habitual certainties and the labels and definitions we and others have given ourselves, what emerges is a pure innocent, joyful, humble, creative, and free consciousness. It certainly is the experience of a more real, authentic self that lies beneath our social masks.

2. The monks themselves were the perfect embodiment of the elegance of simplicity, equanimity, compassion, kindness and joy.

3. The peasants and villagers were generous and giving and in my view, had more happiness then some of the wealthiest people in the world.

4.The awareness of impermanence makes every moment precious, and an opportunity for giving and receiving.

5. Compassion helps us go beyond the illusion of the separate self.

6. Life is a continuum of experiences that occur in an eternal now. When we are grounded in present moment awareness, there is an awakening of innocence, joy, and knowingness that is our essential nature.

7 Understanding and embracing impermanence and being aware of our own death makes every moment precious and reminds us of what is really important in our life so we can be happy and make others happy.

8 We create our own environment. The quiet dignity and serenity of the monks and the villagers who embraced us created an atmosphere of peace, joy, and a feeling of abundance that money cannot buy.

I am back now in New York City and settling to my routine of writing, public speaking, and consulting. What I bring back with me is a fresh and renewed awareness of how we can all be and how this transformation in us can help create a better world.

deepakchopra.com

Follow Deepak on Twitter

More from Beliefnet and our partners