Visualization is courtesy of TheVisualMD.com

Brought to you by Deepak Chopra, MD, Alexander Tsiaras, and TheVisualMD.com

Processed foods are one of the things people are often told to cut back on when they’re trying to follow a healthy diet. In recent years, one particular processed food ingredient, known as high-fructose corn syrup, has been singled out as a possible health risk. Some researchers have suggested that it might be linked to a rise in obesity rates and related health problems like diabetes. What exactly is high-fructose corn syrup? Is it really bad for you?

Processing corn into a sweet liquid Humans have been processing food for centuries, if you consider that “processing” means altering a raw food in order to make it safer, to make it last longer, or to make it taste better. Some of the earliest food processing techniques included using salt to preserve meat and fish and using vinegar to pickle vegetables. Food processing has changed a lot since then, especially with advances in technology. High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is just one example of how sophisticated food processing has become. HFCS is made by using chemicals to transform the starch that occurs naturally in corn into a sweet liquid called corn syrup, made of glucose. The corn syrup is further processed in order to boost its sweetness. An enzyme is added that changes some of the glucose into much-sweeter fructose in a 42/55 proportion, to be exact. (The other 3% is other carbohydrates.) That’s where the “high-fructose” in the name comes from.

High-fructose corn syrup was developed in the 1970s as a cheap, versatile replacement for sugar. During the next 30 years, its use skyrocketed. Today it has replaced sugar as the most common added sweetener in sodas and many other beverages. It is also used in many packaged and processed foods, both as a sweetener and to keep food fresh and prevent browning. It can be found in everything from ketchup, salad dressing, bread, and cereals, to lunchmeats, cookies, and chips.

How is HFCS different from sugar? And is HFCS worse for you than other sugars? Two common sugars in our diet are fructose and sucrose. Fructose occurs naturally in fruits and honey and, as described above, it can be synthesized from corn to create HFCS. Sucrose, or table sugar, is structurally similar to HFCS–its glucose/fructose ratio is 50/50. In many fruits, naturally occurring fructose is found in relatively small amounts. For example, a cup of blueberries contains about 30 calories’ worth. In contrast, many processed foods containing sucrose or HFCS harbor dense concentrations of fructose. A single 12-ounce soda has approximately 80 calories’ worth of fructose (1).

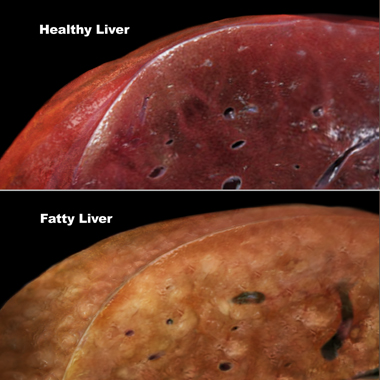

A 2004 study sparked controversy by suggesting that the obesity epidemic in the U.S.—and related health problems like diabetes and high blood pressure—might be linked to the rise of HFCS as the dominant sweetener in soft drinks and other foods. The study suggested that the body digests and metabolizes fructose in liquid form differently from the way it processes glucose. More recent research indicates that the liver processes fructose by converting much of it directly into fat and shipping it to fat tissue. Over time, excessive conversion of fructose to fat results in fatty deposits in the liver, leading to a condition known as “fatty liver disease.” (1) In addition to fatty liver disease, the American Heart Association has recognized that excessive fructose consumption appears to be associated with an array of other health problems. They include increased triglyceride levels in the bloodstream, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension.

The question of whether HFCS is worse for our health than sucrose is still being studied, and there are differing opinions on the topic. Many researchers believe that HFCS and sucrose are essentially identical and have similar effects on the body. However, a recent study out of Princeton University suggests that HFCS may impact our bodies differently, leading to more significant weight gain, especially in the abdominal region, and a greater increase in triglyceride levels than what sucrose contributes.

How much is too much? How much added sugar is ok to eat? The American Heart Association recommends that women consume no more than 100 calories a day from added sugar and men take in no more than 150 calories per day, although less is better. That translates into about 6 teaspoons for women and 9 teaspoons for men. Currently, the average American takes in about 12 teaspoons of high-fructose corn syrup alone per day. That doesn’t include other sugars like sucrose, maltose, and lactose. Some teens and other high-consuming groups take in as much as 80% more HFCS than the average person.

Tips for reducing sugar How do you bring your sugar intake down to a safe level? Moderate your consumption of foods and beverages that contain high levels of sugar. That means avoiding sugary sodas, moderating consumption of 100% fruit juices, and drinking more water. Choose breakfast cereals that contain no added sugars or only small amounts of them. Add fresh fruit to your cereal if you crave a sweeter flavor. Check ingredient labels on packaged and processed foods for added sugars. Look not just for high-fructose corn syrup (sometimes called corn sugar), but also sugar, brown sugar, glucose, dextrose, fructose, fruit juice concentrates, molasses, and syrup.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends substituting foods with naturally occurring sugars in them, like fruits, vegetables, and milk products for foods with sugars that are added during food processing. That way, you avoid eating empty calories, since foods with added sugars tend to have fewer nutrients than foods with naturally occurring sugars. Instead of snacking on cookies, candy, or chips, try fruit, low-fat cheese, or vegetables instead. Once you get used to the taste of foods that don’t have added or processed sweeteners, you’ll find that not only are they good for you, they taste good, too!

Learn more about maintaining your health and well-being:

TheVisualMD.com: The 9 Visual Rules of Wellness

(1) Taube G. Why we get fat and what to do about it. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2011.