I won’t do it often, but tonight I ask you to indulge me. I enjoy writing about the focus of this blog, but tonight I go at it a different way. Although, perhaps it does fit after all as I think of it, since for some of us it is the end of this world.

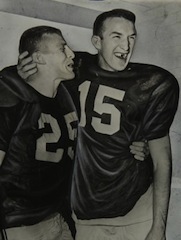

Yesterday, I saw a notice online that Jimmy Harris died. He was 76. For many of you, this won’t mean anything, but to me it is everything. Harris was the quarterback at the University of Oklahoma in the ’50s, when the Sooners ran up a winning streak to 47 games. Harris came in during a game as a sophomore, when Gene Calame went down. He left three years later, and he left undefeated. “47 Straight” is still the crown of the nation’s winningest program of the past half-century.

For OU fans, of course, Harris will always be undefeated. Cocky, confident, and a natural leader, Jim “Jimmy” Harris is the legend of legends at a school with a treasure chest full of championship rings and too many All-Americans to count. Football royalty.

Every school has football fans; some wear ill-fitting jerseys long after they should. Some project more an air of sophistication. Some are poor. Some are rich. But all of us have sat by the radio on a Saturday afternoon, or reveled in the glory of Owen Field, when the red jerseys flit up and down the green field.

Harris was a man my quiet father talked about a great deal. Harris had been the football general at OU when Dad was in his prime. My, how he talked about those great teams! The fabled comeback against Colorado at Boulder, in the snow. The smashings of Nebraska, Texas, and Notre Dame.

Three years ago, I wrote a book about OU football, and I interviewed Jimmy Harris. He took the time to visit with me and answer the same questions he’d been asked for 50 years. He teared-up when talking about what a father figure Bud Wilkinson was; Harris had been fatherless.

Two years ago, with trepidation, I phoned each of OU’s national championship-winning quarterbacks. Claude Arnold (class of ’50!) was first and agreed to show up for a book signing in Norman.

I called Harris next and literally took a few deep breaths. “If Arnold is going to be there, I’ll be there,” he growled. Steve Davis said yes. Jamelle Holieway said yes. Josh Heupel said yes.

A few weeks later, the five appeared for a magical afternoon. Hundreds and hundreds of fans showed up and those five men signed for hours. I stood and talked to Harris, and he clearly was still in command of Oklahoma football, giving his views of the current staff (“top-quality”) and various players (“He was an SOB, but he was good!”).

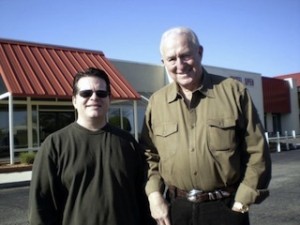

You see, Harris was a rich man, having gotten into the oil business years before. He flew to Norman in his own plane and I picked him up and took him back to the airport. I thought then if Dad could see us, he wouldn’t believe it.

My father died 30 years ago and every autumn, I think about him on Saturday afternoons. Especially during Texas week and Nebraska week. In my memories and his, I close my eyes and see Jimmy Harris, without a facemask on his helmet, stiff-arming an army of TCU Horned Frogs on his way to the endzone. That was in 1954, and Dad had gone with a group of friends from a Catholic school in Oklahoma City—three nuns and a priest.

At the very instant Harris came ’round end and sprinted into the open field, Dad was overcome. He leaped to his feet and turned the air blue and shouted Harris home. A split-second later, astonished, he looked at his friends. Their faces were tight and lips pursed, save one who allowed an almost imperceptible smile to absolve Dad of his sin.

Forty seven years later, during OU’s drive to another national title, I sat in the same stadium with my own son, and I pointed out to him where his grandfather sat during the infamous Harris punt return of 1954. Jonathan smiled at me; I smiled back, and I smiled inside, too.

Jimmy Harris was a gracious gentleman to me, and even though I was a blip on the radar of his life, he will forever be much more than that in my life. He told me that only a decade before, he had run the 40-yard dash one more time, and had only lost a half-second in all those years. Wow! Jimmy Harris told me something great!

I have been very sad the last 24 hours, since learning he had succumbed to lung cancer.

I thought I was getting over it, until I saw Glen Campbell singing “Wichita Lineman” on PBS. Campbell recently announced a farewell tour; he has Alzheimer’s and has asked his fans to be understanding as he figures he’ll forget some lyrics. I am sad for him, too.

Time marches on. This tired old planet has seen too much death. I know that God will one day, in His own time, banish this final enemy and make everything right. I know that.

But for tonight, I think I want to sit in my sadness and think of the men who have meant the most to me—because no matter how old we get, there is always a whisper left of the little boy we used to be.

With each passing year now, I understand better why old folks have often told me they are ready to “go home.” There was a time when I couldn’t understand that insanity. Now I do. The world is losing its legends and there are no replacements. I hate it. Hate it!

Sleep well, Jimmy Harris. My memories of you, of Dad, of those great days in the sun—

I want you for all time.