The last chap of Gary Macy’s

The Hidden History of Women’s Ordination: Female Clergy in the Medieval West demonstrates that the 12th Century saw a new definition of “ordain” and a completely contrary (and historic) view of Abelard (and Heloise).

The various factors that led to the current Roman Catholic viewpoint is traced carefully by Macy, and it involved the following features:

First, ordination was increasingly and then finally completely connected to two “offices”: priest and deacon.

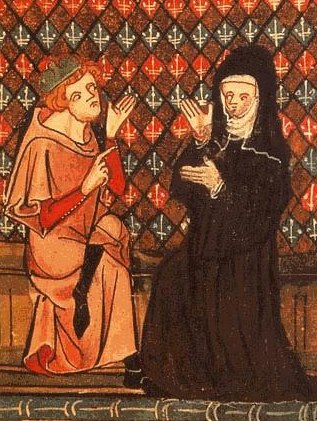

Second, Abelard — the one famous for his relationship to Heloise and for his exemplary theory of atonement — argued strenuously that women had been ordained as priests, bishops and deacons and so could continue to be ordained.

In my judgment, we have to be vigilant to continue to ask this: What does “ordain” mean? What does it “do”? And there’s an important corollary: What is the relationship of “ordain” to “giftedness”? Doe the former lead to the latter or does the latter lead to “ordain” meaning “recognition”? Who “ordains”? God or the Church?

Those who study the decisions of the Catholic Church are called “canonists” and they were the ones who finally changed the picture. Gratian’s famous Decretum was the major influence, even though it somehow managed to include five references to women as “priests” or “deacon/esses.”

But the canonists, like Huguccio, connected “sex” (or gender) to sacred orders and concluded that the female sex was incompatible with the priesthood and there never were deaconesses in the sense that many thought. The logical corollary was drawn: if women were incompatible with the Eucharist liturgy, then they never were ordained; therefore, “ordain” must have had a different meaning in the older days. Thus, real ordination was to the Eucharist and any other kind of ordination was really only a “blessing.”

A final feature: the “ordination” process, which was concerned with empowering someone to bless the bread and wine, bestowed something eternally and metaphysically on the soul of the male so ordained.

So, what led to these basic changes in definition? Macy’s sweeping, at times stunning, conclusion unabashedly sketches the context for these changes. They include:

* the rising power of the papacy and male priesthood,

* the continued elevation in piety for the continent and celibate,

* some drastic — and disastrous — changes in perception of women as women.

Some of this developed into overt misogyny, which came into the church through Roman law and the teachings of Aristotle. Aquinas picked some of this up and sanctified it. (A few of Macy’s quotations, extreme though they are, reveal the depths to which some went.)