In my recent research on the meaning of “gospel,” I read Ted A. Campbell’s new book, The Gospel in Christian Traditions. Here is a book that needs to be read as a primer to theology in the history of the Church. Why? Because theology is the unfolding of the gospel and the gospel alone can contain the contours of the gospel.

In my recent research on the meaning of “gospel,” I read Ted A. Campbell’s new book, The Gospel in Christian Traditions. Here is a book that needs to be read as a primer to theology in the history of the Church. Why? Because theology is the unfolding of the gospel and the gospel alone can contain the contours of the gospel.

This book is designed by a veteran theologian in the ecumenical movement to demonstrate that the church’s unity can be formed on the basis of the gospel.

But perhaps the most important result of this book, a book written in wonderfully clear prose, is how he ties “orthodoxy” to “gospel.” Let me explain:

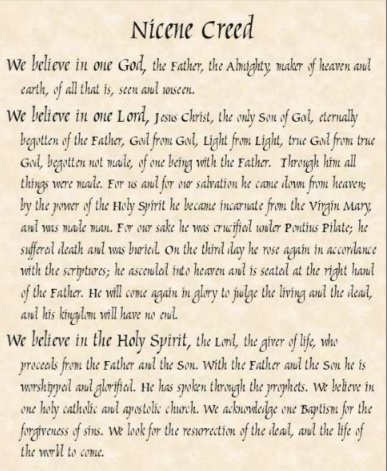

How do you define “orthodoxy”? Do you think one must be “orthodox” to be “saved”? Did “orthodoxy” stop with the NT, with the early creeds (say Nicene, Chalcedon, etc), with the Reformation? Who “defines” orthodoxy?

The foundation for Christian orthodoxy is 1 Corinthians 15:1-5 (most folks say 15:1-4, but I’m not sure that is the most natural of stopping points):

1 Now, brothers, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand. 2 By this gospel you are saved, if you hold firmly to the word I preached to you. Otherwise, you have believed in vain.

3 For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, 4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve.

I want to make a few observations and would like to hear your response:

First, the gospel is a narration of the saving events in the life of Jesus as they bring to fulfillment the Scriptures of Israel.

Second, the events in Jesus’ life are his life, his death, his burial, his resurrection and his appearances.

Third, this narrative forms the basis for salvation, understood here to include the forgiveness of sins. These events accomplish that salvation and the gospel therefore involves the appeal to believe in God’s redemption through these events.

Fourth, all of the early articulations of “orthodoxy” — from the The Apostolic Tradition (Hippolytus of Rome) to Nicea to Chalcedon — are elaborations of this narrative.

Fourth, all of the early articulations of “orthodoxy” — from the The Apostolic Tradition (Hippolytus of Rome) to Nicea to Chalcedon — are elaborations of this narrative.

Fifth, orthodoxy, then, in spite of the yacking of some today, is not speculative theology drawn simply from current philosophical debates but elaborations of the gospel, often in response to threats to that gospel.

Sixth, what is at stake in denying orthodoxy is not simply the “right ideas” or “quaint” ideas but the gospel itself. That which threatens the gospel is articulated by those who are most concerned with the gospel.

Seventh, theology that is done without the framing of the gospel narration of 1 Cor 15 is not gospel orthodoxy. In other words, orthodoxy is the faithful unfolding of that original gospel narrative of 1 Cor 15 and orthodoxy is faithfulness as well to the major unfoldings of that gospel, including such things as the Apostles’ Creed, Nicea, Chalcedon, and the fundamental insights of the Reformation’s solas as they seek to elaborate the gospel narration. (At least for Protestants?)

Campbell’s book goes on to elaborate how the gospel was understood in the Eastern churches, in the liturgies, in Protestant churches, in evangelical circles, in the ecumenical movement, and then he concludes with the mystery of the gospel.