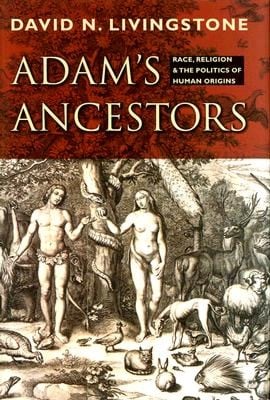

I am currently reading a book by David N. Livingstone, Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion, and the Politics of Human Origins. David Livingstone is Professor of Geography and Intellectual History at Queen’s University, Belfast and this book reflects both of his interests. It is a readable, but thorough and academic, book looking at the history of the idea of pre-adamic or non-adamic humans in western Christian thinking from the early church (Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Augustine) through the middle ages, the explorations of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, the debates on racial supremacy, and on to the present day.

Chapter 3 is “The Cultural Politics of the Adamic Narrative.”

The time span from 1700-1850 witnessed an increasing debate about the origin and diversity of the human race. These discussions were founded at some level in theology, but at a more fundamental level in political and economic aspirations and ideals. There were two primary schools of thought: monogenism where all humans arose from a single source – Adam and Eve. Climate and culture – a combination of environment and the inheritance of acquired characteristics – was proposed to account for the diversity of the human race. In opposition to this idea was polygenism with a separate creation of human pairs in diverse locations with features and traits designed for the local environment. The entire discussion was tied up in the currents of thought regarding imperialism, racism, culturalism, republicanism, and slavery. There is no clearcut demarcation however; both monogenism and polygenism were used to support and refute racism and slavery.

What role does consideration of origins play in the understanding of human persons and human culture? What role does (or did) politics and empire play in consideration of human origins?

Livingstone presents a fascinating sketch of the range of thought and speculation on human origins in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century … far more than can be dealt with in a simple post. Here I will highlight only a few ideas.

Monogenism was coupled with a form of evolutionary change. The anonymous authors of “An Universal History” ca. 1736 considered the ability of climate to produce, via a form of evolutionary change, the various races and traits observed in humans.

After the initial change in skin tone that any group might experience in moving to a “very hot country,” the authors conjectured that “in a generation or two, that a high degree of tawniness might become natural and at length the pride of the natives. The men might begin to value themselves upon this complexion, and the women to affect them the better for it; so that their love for their husbands, and daily conversation with them, might have considerable influence upon the fruit of their wombs, and make each child grown blacker and blacker, according to the fancy and imagination of the mother.” (p. 54)

The influence of climate went beyond physical features however. Montesquieu writing in 1748 described

the influence of northern climate as producing “a greater boldness, that

is more courage; a greater sense of superiority … more frankness,

less suspicion, policy, and cunning. By contrast, the inhabitants of

warmer climates were, “like old men, timorous. (p. 55)” Evolution from a

common pair produced both inferior and superior races of mankind. While

racism and ethnocentrism abounds in the discussion – it is only skin

deep and potentially reversible.

The empire of climate preserved the unity

of the human race; evolution, as it were, saved scripture. And in so

doing, as we will presently note, it also went some way toward giving

sustenance to those who opposed slavery, by combating writers who

erected racial classifications on polygenist foundations. (p. 57)

Many others however saw the diversity of races as evidence for

polygenism. Charles White writing ca. 1799 came to the conclusion that the various races were sufficiently different that climate alone was insufficient. He also made comparisons of human and animal anatomy. He saw connections between species and races of the sort that incorporated the reuse of elements in a gradation and hierarchy but rejected an evolutionary type arrangement.

Indeed, he argued explicitly against any evolutionary-style arrangement, insisting that those who preserved traditional monogenism – and thereby acquiesced to a too-pliable interpretation of racial features – could find no way of drawing a stable boundary between humans and apes. As he put it, if “we admit that such great varieties can be produced in the same species as we find to exist in man, it would be easy to maintain the probability that several species of simiae are but varieties of the species Man … And if the argument be still further extended, almost all the animal kingdom might be deduced from one pair, and be considered as one family; than which a more degrading notion certainly cannot be entertained. Contrary to common assumption, monogenesis did not preserve human dignity, it subverted it. (p. 61-62)

Both monogenism and polygenism, but especially polygenism could be turned to the support of imperialism and slavery. White, quoted above, declared himself against slavery – but his ideas were used to support slavery. Monogenism could be used to support slavery as well – as the climate produced humans of different character and suited to different roles

Monogenism versus polygenism in the New World. The conflicting claims of monogenism and polygenism played a role in the political and moral discussion in the New World as well as Europe – and it went beyond consideration of slavery. Samuel Stanhope Smith (1751-1819, future president of Princeton) wrote to demonstrate that monogenism was good science, good theology, and good moral philosophy. He assigned the savage life to degeneration, yet insisted that the differences were only skin deep.

At bottom, what Smith found so offensive about the speculations of Kames, Monboddo, and White about non-adamic humans was that they were unsuited to the American project, in which it was vital, Smith believes, to have the common constitution to underwrite human morality. In the early days of the new American Republic a confidence in a common human constitution was precisely the philosophy that was needed if public virtue were to be retained in a society “that was busily repudiating the props upon which virtue had traditionally rested – tradition itself, divine revelation, history, social hierarchy, an inherited government, and the authority of religious denominations.” (p. 78)

A republican form of government, eliminating the constraint of monarchy and religious establishment, allowed preservation of morality in the public square “if a universal ethical sense could be extracted from human nature by the methods of empirical science.” (p. 78) Monogenism was thought to be necessary to defend the political philosophy of the US founding fathers.

Interestingly enough – modern evolutionary theory supports monogenism. All modern humans worldwide are one interrelated species. We may not have one unique pair of ancestors as in the traditional reading of the Genesis narrative, but we are one people with one constitution and all descend from one small breeding population some 150k years ago. The unity of the human species is undeniable.

Political, imperial, and cultural considerations have often played a role in the consideration of human origins. Is it the same today? What role do political or moral considerations play in the question of origins? Should these considerations influence our conclusions – or is “pure science” the controlling source of knowledge?

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net