Yesterday afternoon a fellow using the name of “joe” left an interesting comment on one of posts:

“Read the God Delusion you ignorant fools.”

The idea, it seems, is that anyone who thinks, who cares to look at the evidence, will realize that the notion of God is untenable. There is a common perception that higher education draws people away from faith and that the intelligence and atheism, or at least agnosticism, go hand in hand. Certainly Dawkins in The God Delusion pushes this idea with a long

discussion of the negative correlation between education or intelligence

and belief in God (pp. 97-103). Michael Shermer in How We Believe makes the same

general argument.

Elaine Howard Ecklund (Science

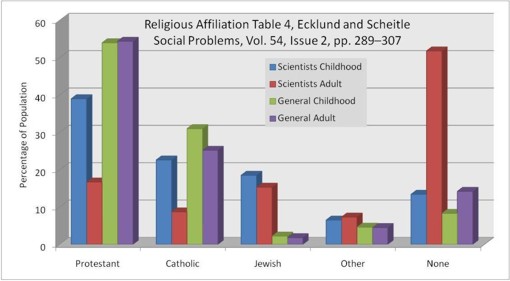

vs Religion: What Scientists Really Think) looked at correlation between childhood religion and adult faith among science professors at 21 “elite” universities. In Ecklund’s survey we see the following trends:

In the general population there is little change in childhood religious affiliation and adult affiliation. Among scientists – all with Ph.D. in hand – there is a clear decrease in religious affiliation for both protestants and catholics. So far so good … are Dawkins, Shermer, and “joe” on to something?

Is the correlation cause and effect? Does education cause a loss of faith?

We shouldn’t be quick to conclude that Ph.D. leads to loss of faith. There are a number of possible reasons for the trends shown in the graph above. (You can find additional discussion at Point of Inquiry.)

Education removes the reason for God. If God is simply an explanation for gaps in understanding this is a plausible explanation.

Education introduces a dissonance, a conflict, between the evidence and the faith. Young earth, evolution, and old testament studies are all places where this comes into play.

The University environment may be hostile to faith. There can be pressure, both overt and subtle leave the faith. To lose the respect of one’s peers is a severe and real possibility.

The group may be self-selected. Education itself doesn’t cause loss of faith – rather people of faith

tend to pursue other career paths.

Ecklund finds that many of those who came from a religious tradition noted that religion was not very important in their families as children. Those from families where religion was important are much more likely to retain faith as adults. For one specific sample group of young scientists Eckland notes that it appears that ~85% retain faith. This is a substantial percentage. But the sample group, those who came from childhood homes with a strong faith tradition, is a small group and the percentage who retained faith is smaller among older cohorts.

Education doesn’t cause loss of faith – rather loss of faith precedes the Ph.D. Ekclund relates stories by several scientists who comment on bad experiences growing up in the church.

About one chemist:

She grew up in what she describes as a “Christian fundamentalist family.” As with many scientists, Evelyn was naturally inquisitive as a child. When she asked questions about the faith, however, she was rebuffed by her religious leaders and told to just believe. … She had been told simply “You just make a decision to believe.” (p. 21)

A physicist:

He was part of a tradition “where you go to church every Sunday, you go out and proselytize, and try to save souls, …you accept Christ as your personal Lord and Savior” The people in his families church were often afraid of any challenges to their faith and provided no forum for asking difficult questions. Worse, their personal ethics seemed inconsistent with living life as Christ lived it. (p. 23)

Another physicist:

He was raised in the Missouri Synod Lutheran church which is “not just any Lutheran church,” … He vividly recalls the minister making him “stand up in front of the church [in confirmation] and say things [he] knew weren’t true,” such as the age of the earth is only a few thousand years. He now thinks the minister forced him to lie because [his] interest in science made him [the minister] nervous. (p. 71)

No place for honest, inquisitive, hard questions and a real or perceived hypocrisy led to loss of faith for all three here – science was involved only peripherally. It was not the facts, it was the attitude.

Much food for thought here. I have two questions I would like to consider today:

Why do we perceive education as antagonistic to faith?

Should people of faith pursue a career path in science – and aim for positions of influence? Is it worth the cost?

Is there something the church can or should do to change the trend?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net