Shakespeare and Dynamic Infallibilism (by David Opderbeck)

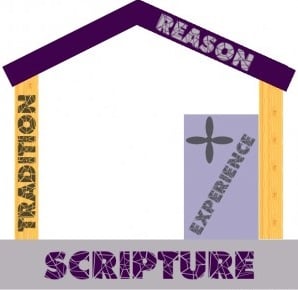

Our recent conversation about inerrancy generated lots of discussion. Although the conversation about this question often becomes heated and difficult, there is one positive note: everyone on this blog is concerned about truth, the authority of the Word of God, the welfare of the Church, and the quality of the Church’s proclamation of the Gospel. In that spirit, I’d like to offer a perspective that seems helpful to me: “dynamic infallibilism.” I came across this term in a wonderful essay by Bruce McCormack in a volume titled “Evangelicals and Scripture: Tradition, Authority, and Hermeneutics” – a volume I highly recommend, if nothing else for the excellent and well-balanced introduction by the editors.

In order to introduce my thoughts, let me start with a question: is William Shakespeare’s play Henry V inerrant? Shakespeare’s Henry V includes the famous “Crispin’s Day” speech, one of my favorite blood-stirring dramatic passages (played in the clip above by Kenneth Branaugh):

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered-

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother

It also includes glorious nuggets such as these: “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more / Or close the wall up with our English dead!” and “Cry ‘God for Harry, England, and Saint George!'” The play is one of Shakespeare’s “Histories,” a number of which dramatize the life of “Prince Hal.”

Henry V, of course, was a historical person, who really did defeat the French at Agincourt on Crispin’s Day in 1415. But did the real Henry V actually give the famous Shakespearian speeches? No — at least not in the words attributed to him by Shakespeare. And there are a number of historical problems with the plot as a whole.Is Shakespeare’s play, then, “in error?” At least concerning the great speeches, I think we would agree that Shakespeare properly employed genre conventions.

The play Henry V is designed as an entertaining drama rooted in historical events, not as a detailed “scientific” account of what happened. One could suggest, therefore, that Shakespeare’s play is not “errant,” despite its questionable facticity and embellishments at many points.

Many conservative evangelicals make the same sort of move with Biblical texts such as the histories in the Hebrew Scriptures. For example, the overlapping histories of Kings and Chronicles cannot be “harmonized” in detail, but this is not necessarily a problem because they reflect a particular type or genre of history that is properly told from a particular perspective for religious and polemical purposes.This sort of genre criticism can be very helpful. At some point, however, genre criticism seems like a wax nose.

As the Shakespeare illustration suggests, almost any text can be called “inerrant” if we allow that the author’s genre permits imprecision or literary license. The only exceptions might be the genres of scientific and technical academic literature and factual news reporting, which are among the very few literary genres in which no imprecision or license are supposed to be tolerated. Certainly, we cannot claim that any part of scripture is a type of literature akin to scientific and technical academic literature or simple news reporting. No capable inerrantist scholar would make any such claim.

But if the flexibility of genre conventions means that Shakespeare’s plays could be “inerrant” in the same sense as scripture, does the concept of “inerrancy” retain any useful content? This comparison suggests to me that we need a “higher” view of scripture than inerrancy as typically formulated. We need to be clear that scripture is like no other text in all of literature, because scripture is the only literary text through which God reveals Himself to us in a way that is finally authoritative for the Church. God does not speak to us through Shakespearian plays, at least not in the sense that He speaks through scripture. How, then, is scripture different?

The difference, I think, comes through the dynamic action of the Holy Spirit speaking in and through the text of scripture as the Spirit’s instrument for the instruction of the Church. Without the Spirit, the Bible is only a human book. It may contain “inspiring” bits akin to Shakespeare’s Crispin’s Day speech in Henry V, and it may provide remarkable historical, religious and moral insights, but could not be considered truly theopneustos, breathed-out by God. As Karl Barth put it:We can even hear Holy Scripture and simply hear words, human words, which we either understand or do not understand but along with which there is for us no corresponding event. But if so, then neither in proclamation nor Holy Scripture has it been the Word of God that we have heard. (Church Dogmatics 5.3).Scripture does not “err” because it is uniquely used by the Holy Spirit to reveal to us who God is, what God is done, and how we are to live in response to God’s glory and grace.

Scripture unfailingly – infallibly – directs us to faith in Jesus Christ and to living conformity with the image of Christ. However, this is a dynamic event that occurs only as we listen prayerfully to what the Spirit is saying in and through scripture. It is a theological mistake, I believe, to try to locate the “inerrancy” or “infallibility” of scripture in the organic quality of the words on the page. Rather, scripture is unerring and unfailing in its application to the believer and to the Church through the instrumentality of the Spirit.This does not mean – as some interpreters (or perhaps mis-interpreters) of Barth suggest – that the organic nature of scripture is irrelevant. No – we carefully study the organic qualities of scripture, including its genres, cultural settings, languages, historical construction, and so on, because all of this is essential and preparatory to sitting under the teaching and revelation of scripture.

God has chosen to communicate in the creaturely medium of scripture, and therefore God has limited His freedom in this regard and has tied Himself to the organic qualities of this particular set of texts. If we think we hear the Spirit saying something that is dramatically different than an organic reading of the text would suggest, we are most likely not listening to what God is saying.Nevertheless, it seems to me that it is a mistake to tie the text’s infallible function as the rule of faith and practice completely to its organic qualities.

This is the mistake – in my judgment – made by B.B. Warfield in his notion of “concursus,” a mistake grafted into the conservative evangelical view of organic inerrancy. Scripture is not “inerrant” like a Shakespearian history could be “inerrant,” merely as a function of its genre conventions. Rather, scripture is unerring, never failing, and always true, as and because it is the Spirit’s instrument and as and because we hear and obey the Spirit speaking through it.

What does this concept of “dynamic infallibility” mean for the hotly disputed historical-critical questions that arise in most discussions of the doctrine of inspiration? It does not “solve” the problem of scripture’s historical content. The organic content matters. But it does mean that we should not expect the organic content to take on a super-human quality in its own right. If we investigate the Biblical texts as human documents and find them to be thoroughly human, that is not a problem – it is expected, and even helpful. We are in trouble, however, when the Bible remains for us only human, when we do not allow the Spirit to wield it as an instrument that cleanses, clarifies, challenges and comforts.