The word “heresy” appears on this blog every now and then, and I have long wanted to do a series on heresy and heresies and have now found a perfect reason: B. Quash and M. Ward, Heresies and How to Avoid Them: Why It Matters What Christians Believe

The word “heresy” appears on this blog every now and then, and I have long wanted to do a series on heresy and heresies and have now found a perfect reason: B. Quash and M. Ward, Heresies and How to Avoid Them: Why It Matters What Christians Believe

. I want to get this conversation started today. I begin with a set of questions:

How do you define “heresy”? Who defines “heresy”? What have you heard — profound and absurd — that was called heretical? Do you think it is important to point out heresy? What are the dangers in pointing out heresy?

This book is an edited collection of readable, brief, and incisive chps on various heresies: Arianism, Docetism, Nestorianism, Eutychianism, Adoptionism, Theopaschitism, Marcionism, Donatism, Pelagianism, Gnosticism, Free Spirit, and the book closes with a study of Bibical Trinitarianism and the purpose of being orthodox.

Hauerwas writes the Foreword and makes the following (always provocative) statements:

“Given the diminished state of the Church some Christians might even believe that if we could gain more members by being heretical so much the worse for orthodoxy.” But, if orthodoxy “is used as a hammer to beat into submission those we think heterodox” it “betrays itself.” So instead of a hammer, “orthodoxy is displayed as an act of love that takes the form of careful speech.” There are limits, and not all stick to the limits: “orthodoxy is the hard discipline of learning to say what needs to be said and no more.” And this one: “Orthodoxy shows why what we believe cannot be explained but can only be prayed.” So Hauerwas.

One of the editors of this fine book is Ben Quash, an Anglican priest, a professor at King’s in London, and the canon theologian at Coventry. The other editor is Michael Ward, an Anglican priest and writer and former chaplain at the coolest college in Cambridge: Peterhouse. Quash wrote the Prologue.

He opens with a definition: “A heretic is is a baptized person who obstinately denies or doubts a truth which the Church teaches must be believed because it is part of the one, divinely revealed, and catholic (that is, universally valid) Christian faith” (1).

Why does this matter? Because our collective faith has “said that neither your race, nor your sex, nor your social class, nor your age could be a bar to full membership of Christ’s body, the Church.” How? “The answer was: your faith — what you believed in, as embodied in your practices and confessed with your lips” (1).

Thus: “The Church’s identity and integrity were expressed in orthodoxy: the confession (and enactment) of a collective belief” (1). Heresy thus threatens the glue that holds the Church together.

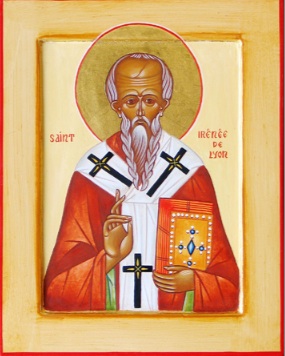

He observes that Irenaeus shows that it is not just their hostility but they way they assimilate themselves to Christian orthodoxy. There is always an air of probability, he says, about heresy. They use Scripture and they tend to be one-doctrine problematizers. Theology is interrelated.

He observes that Irenaeus shows that it is not just their hostility but they way they assimilate themselves to Christian orthodoxy. There is always an air of probability, he says, about heresy. They use Scripture and they tend to be one-doctrine problematizers. Theology is interrelated.

“The key task for orthodoxy, it seems, is to keep a sense of what the larger shape of Christian belief is — a shapw which, if contemplated patiently and sensitively and with a concern to find its maximum integrity, will unlock its inner persuasive power, and display its glory” (5). I totally agree.

He doesn’t trust the individual; he believes the community must make these decisions. Orthodoxy doesn’t create unity; it deepens the unity that is ours through the Holy Spirit.

Heresy is often the easier option.