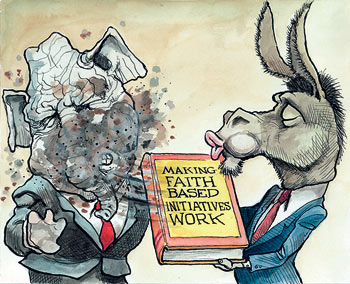

John DiIulio, famed political scientist, Godfather of the faith-based movement, President Bush’s first (and only effective) head of his faith-based initiative, has a new book out. It is entitled Godly Republic and no review I could give it could top what The Economist says of it (and of him).

Mr DiIulio is the ideal salesman for faith-based social services. He is one of America’s leading political scientists—a man who has all the latest data at his fingertips, but who also knows his “Federalist Papers” and his de Tocqueville. In a world where people like to talk about Jesus changing their hearts, he presents the case for “faith” in scrupulously secular terms. He is also one of those rare things in professional America—a working-class boy made good who nevertheless clings on to his roots.

George Bush nicknamed Mr DiIulio “Big John”. He grew up in a tough Italian district in South Philadelphia where he and his friends used to entertain themselves by trying to catch giant water rats. He was the first member of his family to go to university, and went on to do graduate work at Harvard partly because he could not decide whether to go into the building trade or open a hot-dog stand. His career was meteoric: he was awarded tenure at Princeton at 32. And he remains devoted, too, to the other Philadelphia. He works with disadvantaged children and prisoners. He tries to keep decent neighbourhood schools alive. The only time he has been abroad was to visit the Vatican.

But is Mr DiIulio right to think that there is still plenty of life in his idea? Or is he falling victim to the vice of all great salesmen—buying into his own hype? Mr Bush’s “compassion agenda” encountered fierce resistance from both the left (who worried about the church-state divide enshrined in the constitution) and the right (who worried that “with government shekels come government shackles”). Legislation was stillborn. The promised $8 billion a year was squeezed to less than $2 billion. And the Mayberry Machiavellis got their way. The White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives gave conference after conference in target states in 2003 and 2004. The very phrase “faith-based” now summons up images of political zeal rather than compassionate problem-solving. Mr Bush’s critics accuse him of launching “faith-based wars” and supporting “faith-based science”. One White House figure added grist to the left’s mill by talking dismissively of the “reality-based community”.

Reality bites

But Mr DiIulio is nevertheless right that the idea still has a lot of life left in it, for two reasons. First, America has a big problem with what people now call “social exclusion”. Every great city has homeless people on the streets. Over half of black males in the inner cities drop out of school without graduating. Some 2m children have a parent in prison. Second, “people of faith” do a disproportionate share of the heavy lifting when it comes to dealing with exclusion. These are the people who man the soup kitchens and look after prisoners’ children. They are particularly important in the inner-city minority communities that are most ravaged by poverty and crime. Over a third of the institutions that provide social welfare in big cities are religious.

In his new book Mr DiIulio argues vigorously that there is no constitutional problem with giving public money to religious organisations—provided the rules are written tightly and monitored carefully. The Founding Fathers did not intend to banish religion from the public square any more than they intended to create a Christian nation. And much of America’s government work is currently subcontracted to “proxy institutions”. If religious proxy institutions can do the job effectively, then there is no reason to discriminate against them.