Chuck Colson’s formulation, “worldview-induced blindness,” that I noted yesterday helps explain a lot of things. It explains, for example, why believers in Darwinism can’t open their eyes and see when presented with scientific evidence of design in nature. (Note to Darwinist commenters: This is not a blog concerned with presenting that evidence. However, if you’d like additional information on the subject, why don’t you read Stephen Meyer’s new book, Signature in the Cell. After you have read it, then I would be very curious to hear your thoughts about the evidence of intelligent design in DNA.)

Colson’s phrase also neatly captures an idea in the beginning of this week’s Torah reading,

Chukat-Balak (Numbers 19:1-25:9). The reading begins with the description of the statute (

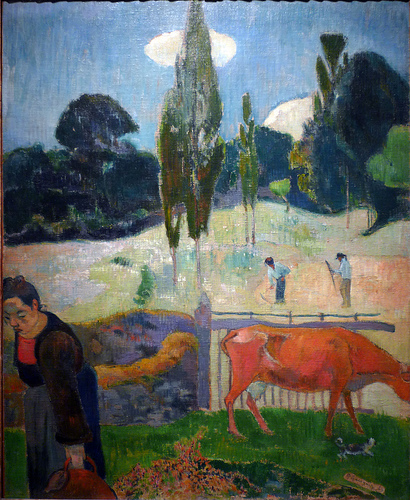

chok) of the red heifer, whose ashes cleanse ritual impurity associated with having come into contact with the dead. According to Jewish tradition, the term

chok, or statute, implies that the kind of law in question differs from other kinds of laws in that its rational basis is not readily apparent. To put it mildly.

Another class of Torah laws — mishpatim, often translated as “ordiances” — are “rational” in the sense that the reason behind them can be discerned without the need for revelation. Many of these are laws that humankind might have arrived at on our own had the Hebrew Bible not been revealed. Think of them as natural law. Some, though not all, of the laws in the Ten Commandments would be examples of this.

But a chok almost seems to invite mockery from the world. On this point, the Medieval commentator Rashi on Numbers 19:2 cites the Talmud (Yoma 67b). Why does the verse speak of the law of the red heifer as “the statute of the Torah,” as nothing less than the prime example of a Torah “statute”?

Rashi answers:

Because Satan and the nations of the world taunt Israel, saying, “What is this commandment, and what purpose does it have?” Therefore, the Torah uses the term “statute.” I [God] have decreed it. You have no right to challenge it.

Sometimes a chok is called a “suprarational” law. That doesn’t mean it’s irrational. Instead, the rationale behind the law, its significance when considered rationally, can only be perceived from within the system of Torah thought — the worldview of the Hebrew Bible. From outside, it indeed appears irrational. An alien worldview, like secularism, blinds a person to being able to see the law’s sense, the insight and beauty it reflects — “worldview-induced blindness.”

I know that such “statutes” aren’t irrational because Jewish tradition has much to say about their meaning. Just yesterday I attended a circumcision and the rabbi spoke movingly about circumcision as a “chok” — brit milah is indeed mocked by many in the secular world — but then he went on to elaborate on its meaning in what seemed, to someone listening from within the Torah’s worldview, a very sensible way, having to do with the permanent engraving of God’s relationship with the Jews as a mark on the human body. Chok is etymologically related to the Hebrew word for “engraved.”

In earlier posts,

we’ve been talking about homosexuality. It is relevant and interesting to glance at Leviticus 18, where many laws of sexually immoral combinations (e.g., incest, bestiality, homosexuality) are given. These laws are prefaced with the statement: “Carry out My

ordiances and safeguard My

statutes to follow them; I am the Lord, your God” (18:4). In other words, looking at the Hebrew, it’s clear that the passage speaks of both “rational” and “suprarational” laws — those whose sense can be readily appreciated from outside the Torah’s worldview and those whose sense cannot be readily appreciated, where worldview-induced blindness comes into play.

The verse doesn’t tell us which laws are which, but maybe we can speculate that the laws against incest would fall under the former category, and against homosexuality, under the latter.

Join our mailing list to receive more stories like this delivered daily!

By filling out the form above, you will be signed up to receive Beliefnet's Daily Bible Reading newsletter and special partner offers. You may opt-out any time.