Last week some readers of this blog had a hard time accepting that the rabbinic term “apikoros,” a kind of heretic, denotes someone who rejects — if I may use the contemporary term — intelligent design. One fellow, by a rigorous Google search, even believed he’d found Internet-based proof that an apikoros designates a Christian! Um, no.

The Mishnah uses the word without explanation, for a category of persons who have no share in the World to Come. The Talmud links it with insolence either to the face of the Sages or in their presence. (See Sanhedrin 90a, 99b.) Maimonides finds an etymological connection to an Aramaic word for “disparagement.” But what of the idea content of the term? In the Mishnah’s context, it’s linked with other heretical ideas. The apikoros is listed alongside other heretics, those who say the resurrection of the dead has no support in the Torah and those who deny the Torah’s divine origins. These are intellectual matters, not merely ones of temperament or manners. In a Hebrew dictionary, it is defined as an “atheist, freethinker, heretic.”

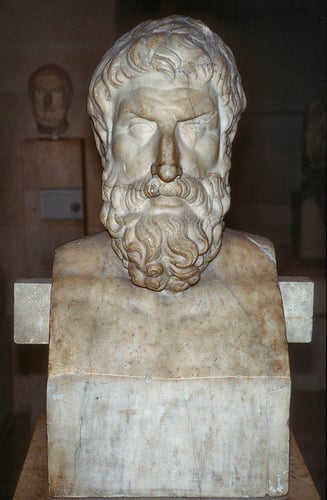

Rabbi Joseph Albo, a medieval luminary, explains the term as referring to the Greek philosopher Epicurus (born c. 342 BCE) and his school (

Sefer ha-Ikkarim 1:10). In Hebrew, Epicurus is “Epikoros.” In case you’re curious, Apikoros and Epikoros are spelled the exact same way, though for some reason the traditional Talmudic pronunciation, unlike modern Hebrew, gives the initial vowel sound as an “a” rather than an “e.” In popular English usage today, an “Epicurean” means someone who seeks pleasure in fine food or wine, but that’s not what Epicurus himself was about. Epicurean thought does stress the pursuit of pleasure but not the short term kind. Rather, it urges us to avoid pain and think in terms of longer term, though not eternal, happiness. Among other things, to escape emotional pain, Epicurus advocated masturbation over sexual relationships.

Part of Epicurus’s program was to eliminate fear of divine justice. The gods, he explained, were off in their distant celestial realm, indifferent to our world. In line with this, the philosopher taught that human life is a purely material affair. Even the soul is made of physical matter. There’s nothing to fear from the gods in part because once you’re dead, your dead. There is no afterlife. This is understood to be a comfort.

Reality, he taught, is purely material, composed of “atoms.” The universe came into being through the unguided colliding of these atoms. “The world is, therefore, due to mechanical causes and there is no need to postulate teleology” — purpose or design — summarizes Frederick Copleston in A History of Philosophy. For the rabbis, this last point is the key to what’s wrong with Epicureanism.

In the classic medieval philosophical work

Kuzari, which takes the form of a dialogue between a rabbi and the king of the Khazars,

Rabbi Yehudah HaLevi makes this explicit. In the Fifth Essay (5:9, 5:20), the rabbinic protagonist teaches,

We perceive [divine] wisdom in many creations, and the necessary purposes they serve….This wisdom was alluded to by King David in the Psalm [104], “How great are Your deeds, God.” He wrote it to refute the arguments of Epicurus the Greek, who believed that the universe came about incidentally [b’mikreh, lit. by chance]….

HaLevi explains:

All phenomena are traceable back to the Primary Cause in one of two ways: either directly from God’s will, or through intermediaries. An example of the first way is the order and assembly that is evident in living creatures, plant life, and celestial spheres. No intellectual person can attribute this to happenstance. It is rather attributable [directly] to the design of the wise Maker.

Emphasis added.

Hear that? No intelligent person would deny the evidence of design in living creatures. That is, nobody would do so unless he was an Epicurean, against which teaching the Jews are called to stand as a witness:

The Jewish people provided every nation with a refutation against the Epicureans, who follow the beliefs of Epicurus the Greek. He said that all things happen incidentally, and that nothing in this world shows evidence of intent from a [higher] sentient being. His colleagues were called hedonists because they believed that pleasure is the ultimate objective and the principal good.

I’ve strictly adhered to the excellent

new translation by Rabbi N. Daniel Korobkin. But if you look at the Hebrew (itself a translation from the original Arabic), you’ll see that the Hebrew word that Rabbi Korobkin translates as “design” (

kavanah) in the second passage quoted above, he translates as “intent” in the third. You could just as well translate that penultimate sentence as, “[Epicurus] said that all things happen incidentally, and that nothing in this world shows evidence of design from a [higher] sentient being.”

Rabbi Korobkin clarifies in a footnote,

Because of his radical beliefs and the wanton behavior of some of his followers, Epicurus was viewed by the Sages as one of the most morally destructive of all Greek philosophers.

Any questions?