As U.S. congregations navigate the post-pandemic landscape, a new report reveals a surprising twist: while income levels have risen, inflation has outpaced those gains, leaving many churches financially vulnerable despite an overall sense of improved fiscal health.

The Hartford Institute for Religion Research authored report, “Finances and Faith: A Look at Financial Health among Congregations in the Post-Pandemic Reality” compares financial health among U.S. congregations between 2020 and 2023, and examines how the pandemic may have impacted that health and prompted changes by congregations in response. The surveys used for the report came from Faith Communities Today (FACT) and the Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations (EPIC) study.

The report begins with a “good news, bad news” tone. The good news is that median congregational income increased to $165,000 in 2023; however, that figure did not keep pace with inflation. In 2010, median income was about $150,000; to account for inflation, the 2023 figure should be nearly $210,000. Thus, while income is increasing, purchasing power has dropped. Interestingly, the percentage of congregations that say they are in “excellent” or “good” financial health increased. In 2020, only about half of congregations described their financial health in those terms; by 2023, that increased to 61 percent.

However, underlying that assessment is the fact that nearly a quarter of congregations operate “in the red,” with expenses exceeding income. Forty percent report that their income and expenses are within $5,000 of each other (in either direction), which suggests that these congregations have very limited flexibility in their budgets to respond to unforeseen challenges.

The report provides additional detail regarding both congregational size and denominational identity which helps readers to further analyze their particular situation with more particularity.

For example:

Congregation Size Median Income

50 or fewer attendees $66,000

51-100 attenders $177,000

101-250 attenders $300,000

250 or more attendees $2 million

The $2 million figure is skewed by very large congregations. The report breaks down this largest category in more detail. For congregations with 251-300 members, the median income jumps to $729,469. Median income declines for churches with 301-400 members, and then increases to over $2.5 million for those above 400 attendees.

The correlation between denominational identity and median income reveals two interesting connections. First, Catholic and Orthodox congregations have a median income of $534,000. In its assessment of sources of funding, the report notes that these congregations often receive significant income from fund-raising events and school tuition, while most Protestant churches do not.

Second, Mainline Protestant congregations have a median income of only $142,000, substantially less than Evangelical Protestant churches. However, in smaller churches, Mainline congregations have a higher median income than other groups. The overall median income significantly declines in churches of 250 or more attendees: in Mainline churches, the median for such congregations is just under $800,000, while in Evangelical churches the figure is over $2 million.

Most significantly, across all categories of churches, 85 percent of income comes from “participant contributions.” Such income includes tithes, offerings, dues, and similar gifts. One-third of churches reported that such contributions were their sole source of income, while 39 percent received additional income from only one other source. Other sources include fundraising events, rental income, endowments, capital campaigns, investments, and school tuition. Rental income and fundraisers each provide an average of four percent of income, while the remaining sources account for approximately one percent each.

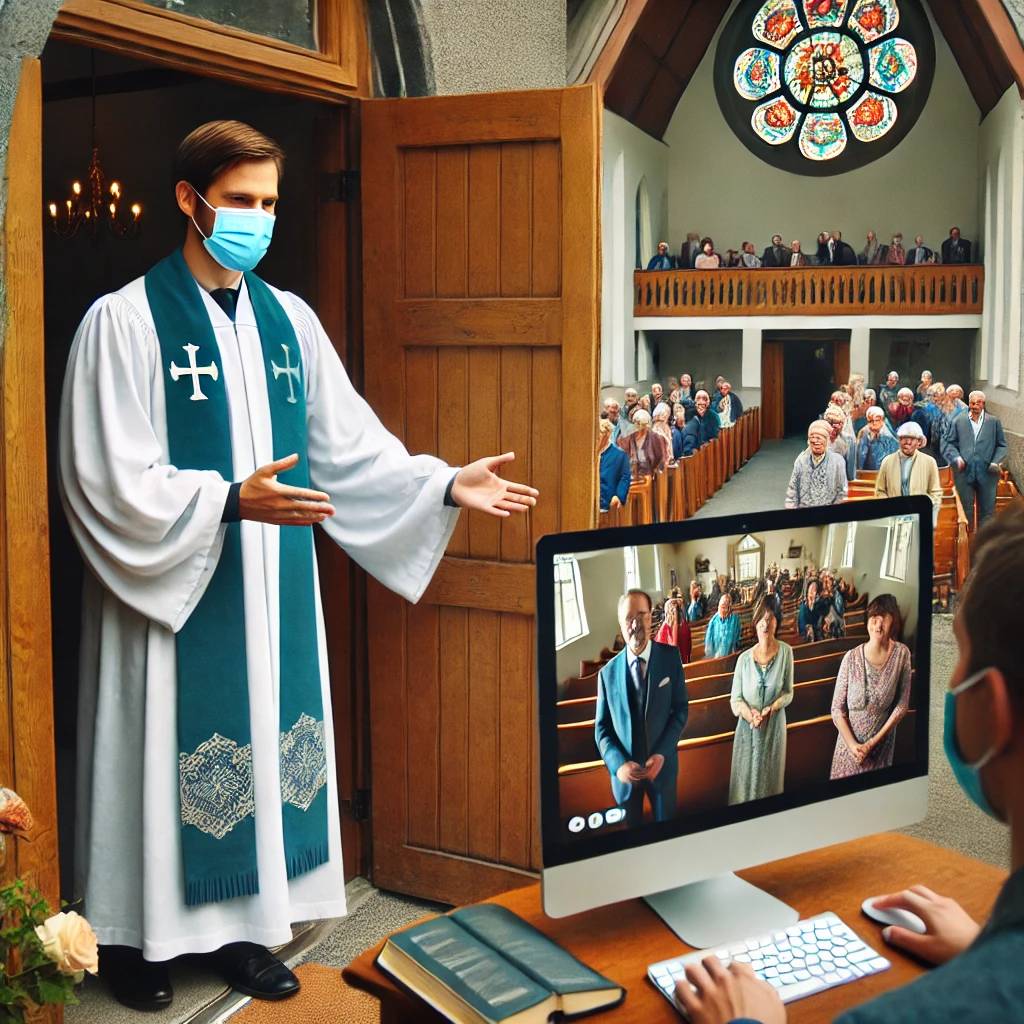

The importance of participant contributions highlights the impact of the pandemic. Many churches stopped meeting in person. Some churches offered virtual worship during that time, while others did not. Virtual worship necessitates online giving opportunities; otherwise, virtual worshipers have no convenient method to contribute. In 2015, only 31 percent of congregations offered online giving; by 2023, that figure increased to 69 percent. Large congregations are very likely to use online giving “a lot,” while only about a quarter of small congregations do. The report notes that online giving still has great potential for growth; only 20 percent of givers utilize online giving, and it provides about 30 percent of total donations received.

Virtual worship clearly provided a way for people to “attend” their congregation during the height of the pandemic. By 2023, hybrid churches – which provide both in-person and online worship – reported higher per-capital income levels than churches that only offer one of those options. Hybrid churches had per capita giving of $2,353, while for those congregations which only offer in-person worship per capita income was $2,000. Churches that only offer online worship had a per capita income of $691. This suggests that in-person connection fosters greater giving; having both worship avenues further enhances that connection.

However, virtual worship is a two-edged sword. While hybrid churches have higher per capita income, that income drops as the number of online worshipers becomes closer to the number of in-person attendees. Churches with roughly equal numbers of in-person and online worshipers have a median per capita income of $1,231. However, those with a ratio of at least 6 in-person worshipers to every virtual attendee report per capita income of twice that amount ($2,479). The report opines that online worshipers may be less likely to contribute financially due to less pressure, lack of options to give, or lower levels of commitment. The difference may be due to the church’s approach to virtual worship. Is it seen as an occasional substitute for in-person attendance, or is it accepted as a viable long-term option? A higher ratio of in-person to virtual attenders would seem to reflect the priority of in-person worship, and a resulting higher level of commitment to the mission of the church.

Financial health – of both congregations and clergy – seem to have been only minimally impacted by the pandemic. In 2020, six percent of churches reported that they were in “serious difficulty.” By 2023, that figure had been cut in half. At the other end of the spectrum, about half of congregations reported “good” or “excellent” financial health in 2020; that increased to 61 percent in 2023. The report suggests that this may have been due to increased giving during the pandemic, along with a heightened sense of responsibility to support the church. Of course, the pandemic also brought government loans and stimulus checks which temporarily enhanced financial health. Those additional sources of income have now disappeared; it remains to be seen whether the improvement in financial health will continue.

Clergy leaders reported a median “financial health score” of 7.1 on a scale of 0-10 in 2023. This represented an increase of more than a full point over 2020. However, there are a few warning signs here as well. First, older clergy, clergy in larger churches, and clergy from Mainline Protestant denominations were more likely to be in good or excellent financial health. Younger clergy face greater challenges, such as higher student debt and smaller congregations.

Second, as expected, there is a significant correlation between the financial health of the congregation and that of its leader. Nearly half of those who lead churches with serious financial difficulties report their own financial struggles. Conversely, 42 percent of those who lead churches with “excellent” finances also report “great” personal financial health.

Third, about a quarter of clergy reported that they had paid employment outside their ministry. The median number of hours worked in such secular employment was 30 hours per week (which does not bode well for the financial and spiritual health of the congregation). Surprisingly, between 15-20 percent of those working in “full-time” ministry roles also reported having outside employment. This may mask the degree of financial struggles that these ministry leaders are facing.

The report concludes: “The net economic result of the pandemic was that financial giving increased.”

However, as the details of the report show, the truth is not so simple.

“It is not entirely clear whether the changes introduced such as online giving, increased giving, and virtual attendance will continue over the long run… One thing that is certain for congregations and non-profits generally; this is a time of challenge and transition which requires creative thinking about the ways an organization’s mission can be funded and sustained into the future.”