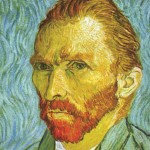

More than 120 years ago this week, Vincent Van Gogh died of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound. In his short life, Van Gogh produced hundreds of watercolor paintings, sketches, and prints – some of which are the most valued in the world – now fetching tens of millions of dollars at auctions or private sales.

More than 120 years ago this week, Vincent Van Gogh died of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound. In his short life, Van Gogh produced hundreds of watercolor paintings, sketches, and prints – some of which are the most valued in the world – now fetching tens of millions of dollars at auctions or private sales.

Van Gogh’s posthumous success is a tremendous surprise, for his life was considered all but a mournful disaster. He was an insufferable friend; his struggles with mental illness, depression, malnutrition, insomnia, and alcoholism were well-known; and he failed at a number of attempted careers.

One of those career choices was the Christian pastorate. “God has sent me to preach the Gospel to the poor,” Vincent wrote to his brother while still a young man in his twenties. So off he went to Amsterdam to enter the seminary, but Van Gogh failed the entrance exam. Undeterred, he entered a missionary school in Brussels. He flunked out after only three months.

Still resolute in his chosen vocation, he convinced the Dutch Reformed Church to appoint him as a missionary pastor to the coal miners in the village of Borinage. There he succeeded in his own way. Broken-hearted by the poverty of the village and his parishioners, Van Gogh gave away all his possessions to the miners. He lived like a beggar himself, barely surviving.

When the church authorities came to inspect his successful and growing ministry, they were appalled by him and his appearance. They removed him from his position because he “undermined the dignity of the priesthood.” Vincent never seemed to heal from this wound; a wound that played a role in him turning to the easel for the first time.

In one of his iconic paintings, “The Church at Auvers” (view it online), Van Gogh’s pain from being rejected by the church bleeds off the page like his hues of blue and starry nights. It is a painting with a road leading to a massive house of worship. Yet the path, upon arriving at the church, is suddenly diverted.

The road bypasses the stately church, and here is why: This church has no doors. After being rejected by the church, Van Gogh concluded that there was no way for him to get in. For him, religion was an empty room with no doors, and this painful discovery broke his heart. Yet, this pain played a significant role in his majestic creativity.

Feeling like his calling had been redirected, Van Gogh picked up his brush as an artist in God’s service. The one rejected by the church for going to the rejected, said, “The great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces what leads to God. One writes it in a book; another in a picture.”

It was Vincent Van Gogh’s pictures – his interpretations of his surroundings – that he used to lead people to God. And he did so with all his rough edges and broken pieces; his fragmented mind and his constant illnesses; with his short, remarkable life; bringing the world priceless joy out of tremendous personal pain.

Bob Dylan was right when he sang, “Behind every beautiful thing there’s been some kind of pain.” Such is the case of tragic geniuses and such is life. Our journey through life is a pilgrimage of inexpressible joy and excruciating suffering. It is the constant rising and falling of the path beneath our feet, pushing us harder and higher until we despair, but giving us great views of the land below us.

Every pilgrim’s journey is a mingled pathway of sorrow and rejoicing; of birth and death; of both pain and joy; of difficulty and satisfaction. Some of it we understand and it makes sense; and a lot of it leaves us with the question marks of hopelessness.

But somehow there is joy behind the suffering, and resourcefulness behind the aching. There is purpose behind the rejection, and in one way or another, there is a future behind the knockbacks that life deals. Truly, the pain can lead to something extraordinarily beautiful.

Ronnie McBrayer is a syndicated columnist, speaker, and author of multiple books. You can read more and receive regular e-columns in your inbox at www.ronniemcbrayer.net.