Roger Williams arrived in the Massachusetts Bay colony ten years after the first Pilgrims. He was part of that Puritan effort to build a “city on a hill,” to prove to the nations of the world how God’s people were to live.

Roger Williams arrived in the Massachusetts Bay colony ten years after the first Pilgrims. He was part of that Puritan effort to build a “city on a hill,” to prove to the nations of the world how God’s people were to live.

How did it go? Not so good. Roger settled into his new role as pastor of the church in Salem, Massachusetts, and his sermons ignited a blowback of controversy. His strange ideas were not well received.

What was it that caused Roger Williams so much trouble in the New World? Well, he believed the Native American tribes should be treated with dignity and paid with more than the small pox for the land the Crown was stealing from them.

And he believed that the state had no right to enforce religion on people. See, Roger Williams believed in the revolutionary idea that there should be a separation between church and state. In Roger’s day, this was like dropping an atomic bomb.

Consider the world of the Puritans: Fail to show up at church on Sunday, and the authorities might appear at your door Monday morning to put you in jail. If you didn’t tithe on your income, the governor of the state would increase your personal taxes.

If you were running for office you had better get the endorsement of the local minister, for only those he deemed godly could be elected. Oh, and when it came to voting, only those members of the church who were in good standing were allowed to vote in civil elections.

The control over society was so strong, that if you had a guest in your home for longer than two weeks – an outsider from beyond the township – you were fined for allowing them to stay. If they refused to leave, both the host family and the guest ran the risk of being put into the stockade until compliant.

To this, Roger Williams could not yield. He relentlessly preached liberty of conscience and freedom from state-driven religious maltreatment. Vexed to the point of lunacy, the authorities finally made plans to kidnap Williams and deport him to England as an enemy of the Crown, where he would be executed.

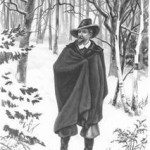

He was warned just hours before the authorities arrived. So in January 1636, Roger left his wife and newborn daughter in the protective hands of his friends and left the village of Salem in the middle of the night, escaping into the wilderness.

He survived that New England winter and eventually purchased from the Narrangansett tribe, the land that would become the state of Rhode Island. Rhode Island became a haven for all kinds of religious dissidents in the earliest years of the American colonies. Roger Williams became a name associated with freedom, toleration, and liberty.

But do you remember what happened back in the village of Salem? Just five years after the death of Roger Williams, twenty men and women were put to death at Salem for the alleged crime of witchcraft.

Thirteen more of the accused died in prison before they could be tried, and hundreds of people were caught up in accusation and allegation as the religious hysteria machine ran rough shod over the Massachusetts colony.

All of this began in that little church at Salem, Mass. That little church that spurned the words of freedom and grace; that little congregation that refused Roger Williams’ appeal for toleration and liberty of conscience.

These were not jihadists. These were professing Christians – our Evangelical and Protestant forefathers – putting people to death over issues of faith, on American soil.

It was no wonder, when John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts asked Roger to recant of his beliefs, leave the Indians of the wilderness, and come home, Roger responded, “I cannot; for I feel safer down here among the Christian savages…than I do among you savage Christians.”

The law that exiled Roger Williams to the wilderness was not repealed until 1936 when the Massachusetts House finally ending three hundred years of calling Roger Williams a heretic. But I would rather be called a heretic, if that means having the freedom to follow Christ, than remain chained to the abusive religious systems of manipulation.

That is what it means to leave Salem. And that is what it means to be free.