Il n’y a pas d’amis : il y a des moments d’amitié.

There are no friends: there are moments of friendship.

Jules Renard

Making it in the mainstream media has and continues to be one my goals. However, controversy is fun, and a useful fire. Kindling it makes life less boring.

Browse my fiction and nonfiction contributions to the Amazon Kindle store

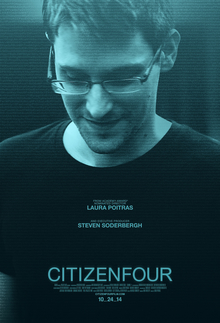

There is a tension, perhaps a clash of philosophy, between established journalists and Internet bloggers/dissidents. This clash is discussed to an interesting degree in Luke Harding’s The Snowden Files, when Harding is characterizing the new species of journalist that Glen Greenwald belongs to. One publication that rests at the boundary between the established journalists and the bloggers is The Guardian. It is a respected news source, but it also has some of the most prominent blogs and has covered issues that most of the mainstream media tried to ignore, including being the first to cover the Snowden leaks.

As I recently wrote in an op-ed at Press TV, published as “No true freedom of expression in US” (Press TV’s title, not mine), I believe The Guardian‘s reporting may have deteriorated and turned them into the courtiers of power that Greenwald despised. Since the UK government forced it to smash its own hard drives and dragged it to hearings where they questioned its national loyalties in an archaic fashion, The Guardian seems to have made itself less radical. I believe this is a great loss for democracy and freedom of expression.

There may be no official political censorship model in the US and UK, but prominent media sources do tend to put their careers over the truth and it causes them to court ruling politicians and deny a platform for the best critics. The effect of this is as bad as totalitarian censorship. In fact, the only reason the totalitarian censorship model isn’t being pursued by the oligarchs may simply be that they don’t find it necessary, for purely technical reasons. The openly autocratic regimes of the world are in weaker, more isolated countries where they feel it is necessary to cut people off from foreign propaganda. In the US and UK, our governments are bought and run by the very same corporations making the propaganda and with the highest technical skill in it.

As our mainstream media have the distinct advantage in funding and reach over their counterparts in more isolated and poorer countries, they don’t need to employ overt means of censorship (although on occasion, foreign media like Press TV and RT have gained significant audiences and on those occasions our governments did consider overt means of censorship). The difference between a poorer country censoring information and a richer country allowing freedom of expression is less about a difference of values than a difference of technologies, a bit like the difference between poorer countries using live rounds against protesters while richer countries can afford rubber bullets and tear gas. It has nothing to do with the richer country having more respect for human rights, but being more technologically advanced and therefore having a broader set of options for suppressing dissent. We too often ignore this difference of technologies, and invariably end up condemning the world’s poor as unfree and praising the rich as free. It is why we accuse countries like Syria or Iran of being exceptionally restrictive or brutal towards their populations, when the reality is that they simply had less tear gas and other means of crowd control than our “democratic” governments have. If our governments only had sabers and bayonets at their disposal, do you think our own police and army would remain so hesitant to kill us?

It is also easy to accuse poorer or more isolated countries of censorship than it is to accuse the rich and well-connected ones, even when the latter are doing it overtly. Our own western media is being aggressively screened by the same oligarchic controllers who lobby the government and are effectively the real, de facto ruling oligarchs. These are the people who control the technological platforms of freedom of expression, and they do it in a way that is devastating to the people they don’t like.

The best role of a blogger in all of this is to be controversial and challenge the mainstream media narratives. If we don’t do this, we might as well not put pen to paper at all. There are plenty of politicians to enforce the status quo, and so writing in devotion and support about them isn’t playing any role at all in journalism. We are part of a new medium on the Internet, and should use it to reform the way people think about politics rather than perpetuate old ignorance.