Yesterday the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the University of California – Hasting College of Law against the Christian Legal Society. You can read the official opinion here on Christian Legal Society v. Martinez (U.C. Hastings) here (PDF download).

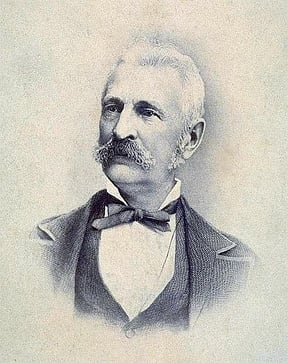

The issue at hand had to do with the freedom of a religious organization (the Christian Legal Society chapter at Hastings) to require its members and leaders to adhere to a basic statement of faith and Christian ethics. This led Dean Leo Martinez of Hastings to refuse to give official recognition to the CLS chapter, arguing that their policies were discriminatory. CLS filed suit, taking the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which held in favor of Hastings. This means, as I understand it, that the CLS cannot be officially recognized by the law school, cannot use its facilities, and cannot receive any official support of the sort that is given to recognized student organizations. (Photo: Serranus Clinton Hastings, 1813-1893, founder of Hastings College of Law)

The issue at hand had to do with the freedom of a religious organization (the Christian Legal Society chapter at Hastings) to require its members and leaders to adhere to a basic statement of faith and Christian ethics. This led Dean Leo Martinez of Hastings to refuse to give official recognition to the CLS chapter, arguing that their policies were discriminatory. CLS filed suit, taking the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which held in favor of Hastings. This means, as I understand it, that the CLS cannot be officially recognized by the law school, cannot use its facilities, and cannot receive any official support of the sort that is given to recognized student organizations. (Photo: Serranus Clinton Hastings, 1813-1893, founder of Hastings College of Law)

Is this a threat to religious liberty? Yes and no. It certainly sets a chilling precedent. I’m no legal scholar, but it certainly seems that the Supreme Court decision could lead to scary places, like disallowing any religious group with any standards whatsoever from using any public facility for any religious purpose. I realize that CLS v. Martinez considered a more focused issue, but the implications are unsettling.

Perhaps even more unsettling was an interview of Dean Leo Martinez, the transcript of which appears on the PBS website for the Religion and Ethics Newsweekly. Here are some excerpts from that interview, conducted by Tim O’Brien:

MARTINEZ: We are a public institution. When we admit students, we tell them we will admit you regardless of your beliefs, regardless of your race, regardless of whether you’re striped or not, and I think part of our promise when they come here is that they are allowed to share in the full educational experience of Hastings, and I think it’s a terrible thing that we would have to do to say, “Yes, we will admit you. Oh, but by the way there are certain groups where you’re not welcome.” And to the extent we’re a public institution and we’re using public money to fund our student groups, I think we simply can’t do that. . . .

O’BRIEN: Would a student chapter of, say, B’nai B’rith, a Jewish Anti-Defamation League, have to admit Muslims?

MARTINEZ: The short answer is yes.

O’BRIEN: A black group would have to admit white supremacists?

MARTINEZ: It would.

O’BRIEN: Even if it means a black student organization is going to have to admit members of the Ku Klux Klan?

MARTINEZ: Yes.

O’BRIEN: You can see where that might cause some consternation?

MARTINEZ: Well, there’s a Spanish saying to the effect that “the thinnest of tortillas still has two sides,” and the other side of that is that with any other regime we would be forced, using public money, to subsidize the discriminatory practices of a particular group.

Out of curiosity, I checked the Hastings website for a list of student groups. Here are some I found listed:

Armenian Law Students Association (ALSA)

Asian Pacific American Law Student Association (APALSA)

Black Law Students Association (BLSA)

Clara Foltz Feminist Association (CFFA)

Hastings Ballroom Dance Club

Hastings Catholic Law Students Association (HCLSA)

Hastings Chinese Law & Culture Society (HCLCS)

Hastings Democrats

Hastings Jewish Law Students Association (HJLSA)

Hastings Vietnamese American Law Society (VALS)

Hastings Women’s Law Journal (HWLJ)

Iranian Law Students Association (ILSA)

Japanese Law Society

Korean-American Law Students Association (KALSA)

La Raza Law Students Association

Law Students for Reproductive Justice

Middle Eastern Law Students Association (MELSA)

Native American Law Students Association (NALSA)

Pilipino American Law Society (PALS)

South Asian Law Students Association (SALSA)

I certainly wonder if all of these groups are held to the same standard as the CLS chapter. Do they admit all students, not only as members, but also as leaders, without regard to what the students believe or practice? Is the Black Law Students Association required to accept white students, not to mention white racists? Is the Clara Foltz Feminist Association open to male chauvinist pigs? Does the Ballroom Dance Club have to let klutzes like me be in leadership? Does the Catholic Law Students Association have to admit those who hate the Catholic Church? Do the Hasting Democrats allow Republicans as members and welcome them into leadership? Do the Hasting Republicans welcome Democrats? (Oops. It appears that there is no such group at Hastings.) Would the Law Students for Reproductive Justice be expected to include members of are pro-life?

I wonder if Dean Leo Martinez has examined all of these organizations carefully, to make sure that they are open to all comers?

I am not equipped to evaluate the legal issues at stake here, but I do worry that the vision of supposed liberty and equality embodied in the Hastings policy is, in fact, opposed to genuine liberty and equality. It sounds to me strangely similar to European states outlawing the wearing of burqas and niqabs by Muslim women who freely choose to wear these garments as an expression of their faith.

It seems to me that the Supreme Court’s decision in Christian Legal Society v. Martinez stands as a huge warning to all religious groups. The potential for the government to limit religious freedom is present in the United States every bit as much as in Europe. In particular, CLS v. Martinez is a red flag for religious groups who seek any benefit or help from the government. It also should spur us to action in supporting organizations that seek to uphold traditional religious liberties in the United States. The beneficiaries of this effort would be, more often than not, religious people who are not Christians.

The news for the Christian Legal Society is not all bad, however. The students can surely meet in some off-campus location, where their free association is protected (at least for now). And, with the power of the Web, they can easily promote their presence and their causes among the students at Hastings (at least for now, but if the government claims sovereignty over the Internet . . . ). Nevertheless, the decision of the Supreme Court in CLS v. Martinez is most troubling, not so much in its specific application, but in its broader implications for religious freedom in the United States.