So far in this series, I’ve presented the case that Jesus spoke Aramaic as his first language and in a substantial portion of his teaching, especially when he was speaking with average people in Galilee, where Aramaic was the common language of the day. I have also suggested that it’s likely that Jesus spoke Hebrew, which he learned as a Jewish boy in a faithful family. His facility with Hebrew enabled him to read the biblical text in the synagogue and to engage in respectable debate with other Jewish teachers of the day (the Pharisees, the scribes, etc.).

But could Jesus have known Greek as well? Might he have used Greek at times in his teaching, or at least in some of his conversations?

Because the manuscripts of the Gospels are in Greek, we do not have the advantage such as we have in the case of Aramaic, where Aramaic words and phrases are actually transliterated and included in the Greek text of the Gospels. Quotations of a Greek-speaking Jesus would not stand out, and would simply flow with the Greek text.

Every now and then, I have run into commentators who argue that some of the sayings of Jesus imply that he knew Greek. If, for example, there is a play on words that works in Greek but not in Aramaic or Hebrew, this points to a Greek original. At this moment I can’t remember any specific examples. Perhaps a commenter can fill us in. But, to this point, I have not been convinced that any of the sayings must have had a Greek origin. I have been more convinced by those who propose a Semitic (Aramaic or Hebrew) original for the sayings of Jesus.

So, the evidence for Jesus’ speaking Greek will be circumstantial only. But this evidence is not insignificant.

The fact that the Gospels are written in Greek bears shows that many if not most of the earliest Christians, including some who followed Jesus during his earthly ministry, knew Greek and used it often, perhaps as their first language. Many Jewish writings from the era of Jesus were written in Greek, including works such as 2 Maccabees and 1 Esdras. Other Hebrew writings were being translated into Greek in Jerusalem (the book of Esther, for example, in 114 B.C.). Speaking of Jerusalem, scholars have found some ninety Greek inscriptions on ossuaries (boxes for bones) that date to around the time of Jesus and were found in or around Jerusalem.

Ever since Alexander the Great conquered Palestine in 332 B.C., Greek had been the language of government and, increasingly, commerce and scholarship. Though Aramaic continued to be spoken by many, Greek grew in its popularity and influence. In the time of Jesus, well-educated Jews, mainly those of the upper classes, would have known and used Greek. So would those who were involved in trade or government. But many other Jews would have had at least a rudimentary knowledge of Greek which they used in their business and travels to the larger cities.

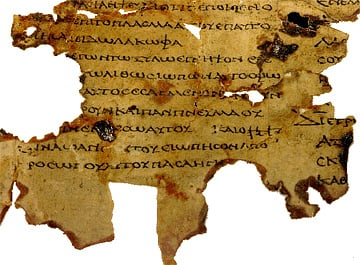

The presence and pervasiveness of Greek in Palestine is demonstrated by a discovery in the Nahal Hever region of the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea. In a cave, a scroll was found that contains substantial portions of the minor prophets in Greek. The so-called Nahal Hever Minor Prophets Scroll, dated around the time of Jesus, shows the influence and popularity of Greek, even among highly religious Jews. (Photo: A portion of the scroll found at Nahal Hever. This shows a passage from Habakkuk 2-3. Notice that the letters are all capitals and there are no spaces between words. That was commonplace in the first century.)

The presence and pervasiveness of Greek in Palestine is demonstrated by a discovery in the Nahal Hever region of the Judean Desert near the Dead Sea. In a cave, a scroll was found that contains substantial portions of the minor prophets in Greek. The so-called Nahal Hever Minor Prophets Scroll, dated around the time of Jesus, shows the influence and popularity of Greek, even among highly religious Jews. (Photo: A portion of the scroll found at Nahal Hever. This shows a passage from Habakkuk 2-3. Notice that the letters are all capitals and there are no spaces between words. That was commonplace in the first century.)

Though the New Testament Gospels do not tell us whether Jesus spoke Greek or not, they do describe situations in which it’s likely that Greek was used. In Matthew 8:5-13, for example, Jesus entered into dialogue with a Roman centurion. The centurion almost certainly spoke in Greek. And, as Matthew tells the story, he and Jesus spoke directly, without a translator. Of course it’s always possible that a translator was used and simply not mentioned by Matthew. Still, the sense of the story suggests more immediate communication, which would have been in Greek.

The same could be said about Jesus’ conversation with Pontius Pilate prior to his crucifixion (Matthew 27:11-14; John 18:33-38). Once again, there is the possibility of an unmentioned translator. But the telling of the story points to a Greek-speaking Jesus. (Pilate would have used Greek, not Latin, as imagined by Mel Gibson in The Passion of the Christ. And it’s unlikely that he would have known or used Aramaic. Pilate was not the sort of man who would stoop to use the language of common Jews.)

If Jesus knew enough Greek to converse with a Roman centurion and a Roman governor, where did he learn it? Some have suggested that he might have learned it during his early years in Egypt. A more likely explanation points to his location in Galilee. Though Aramaic was the first language of Nazareth, Jesus’ hometown was a short walk from Sepphoris, which was a major city and one in which Greek was spoken. Jesus quite probably had clients in Sepphoris who utilized his carpentry services, and he would have spoken with them in Greek.

But given the multi-lingual context in which Jesus lived, it’s not surprising that he would have been reasonably fluent in Greek and Hebrew, in addition to Aramaic. People in the United States often have a hard time understanding this. But if you’ve known people who have grown up in Europe, for example, they often can get by in several languages, including English, German, Spanish, and French, even if their first language is Italian.

Can we know for sure that Jesus spoke Greek? No. Is it reasonable to assume that he could speak Greek and did upon occasion? Yes, I believe so. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if some of the variations in the Gospels among the sayings of Jesus reflect that fact that he said more or less the same things in Aramaic, Hebrew, and/or Greek.

In my next and final post in this series, I’ll suggest some reasons why I think the language of Jesus matters . . . or, better, why the languages of Jesus matter.